Chapter 14. The Ethereum Virtual Machine

At the heart of the Ethereum protocol and operation is the Ethereum Virtual Machine, or the EVM for short. As you might guess from the name, it is a computation engine, not hugely dissimilar to the virtual machines of Microsoft's .NET framework or interpreters of other bytecode-compiled programming languages, such as Java. In this chapter, we take a detailed look at the EVM, including its instruction set, structure, and operation, within the context of Ethereum state updates.

What Is the EVM?

The EVM is the part of Ethereum that handles smart contract deployment and execution. Simple value-transfer transactions from one EOA to another don't need to involve it, practically speaking, but everything else will involve a state update computed by the EVM. At a high level, the EVM running on the Ethereum blockchain can be thought of as a global decentralized computer containing millions of executable objects, each with its own permanent data store.

The EVM is a quasi-Turing-complete state machine: "quasi" because all execution processes are limited to a finite number of computational steps by the amount of gas available for any given smart contract execution. As such, the halting problem is "solved" (all program executions will halt), and the situation where execution might (accidentally or maliciously) run forever, thus bringing the Ethereum platform to a halt in its entirety, is avoided. We'll explore the halting problem in more detail in later sections.

The EVM has a stack-based architecture, storing all in-memory values on a stack. It works with a word size of 256 bits, mainly to facilitate native hashing and elliptic curve operations, and it has several addressable data components:

- An immutable program code ROM, loaded with the bytecode of the smart contract to be executed

- A volatile memory, with every location explicitly initialized to zero

- A transient storage that lasts only for the duration of a single transaction (and is not part of the Ethereum state)

- A permanent storage that is part of the Ethereum state, also zero initialized

There is also a set of environment variables and data that is available during execution. We will go through these in more detail later in this chapter.

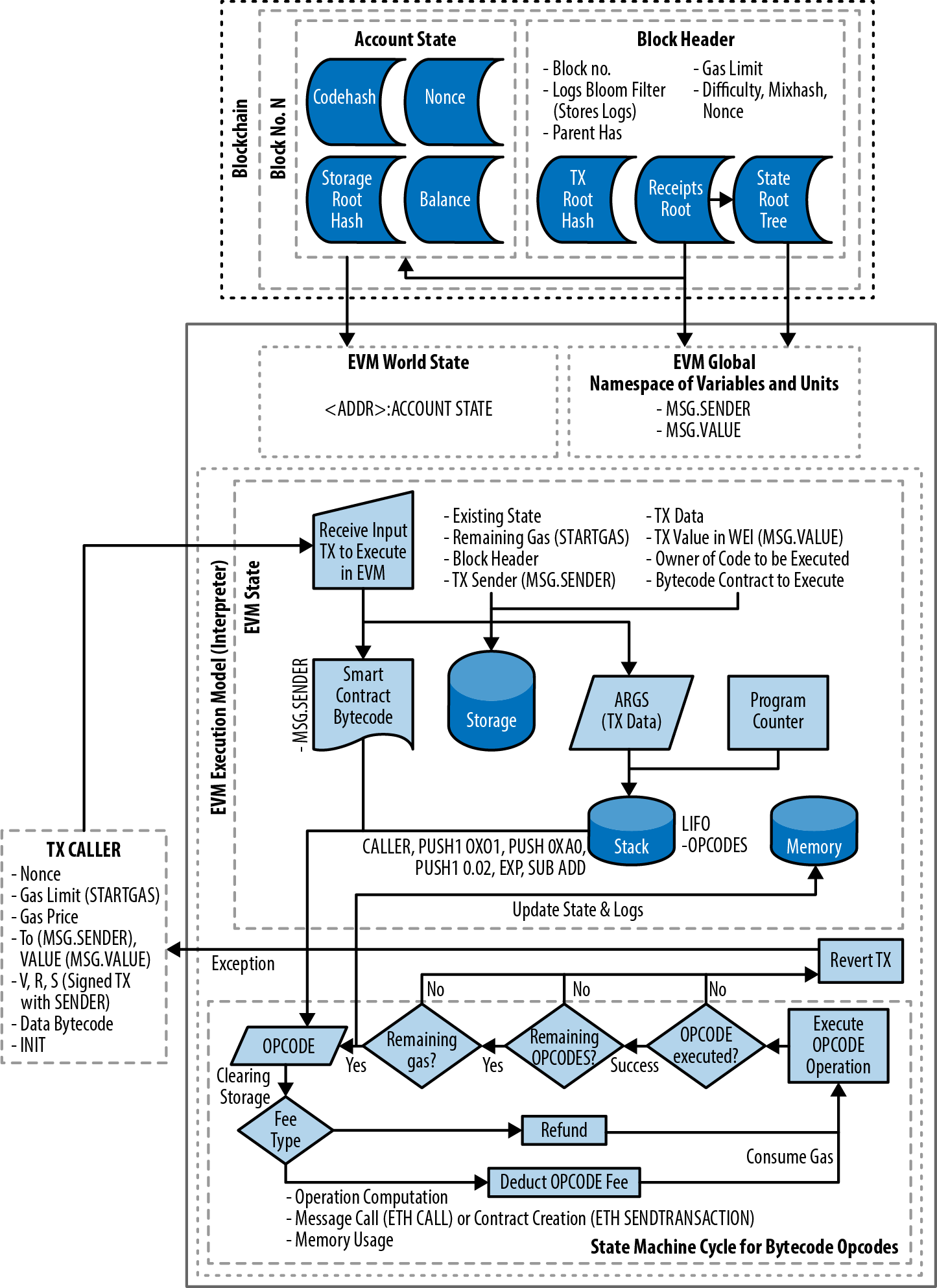

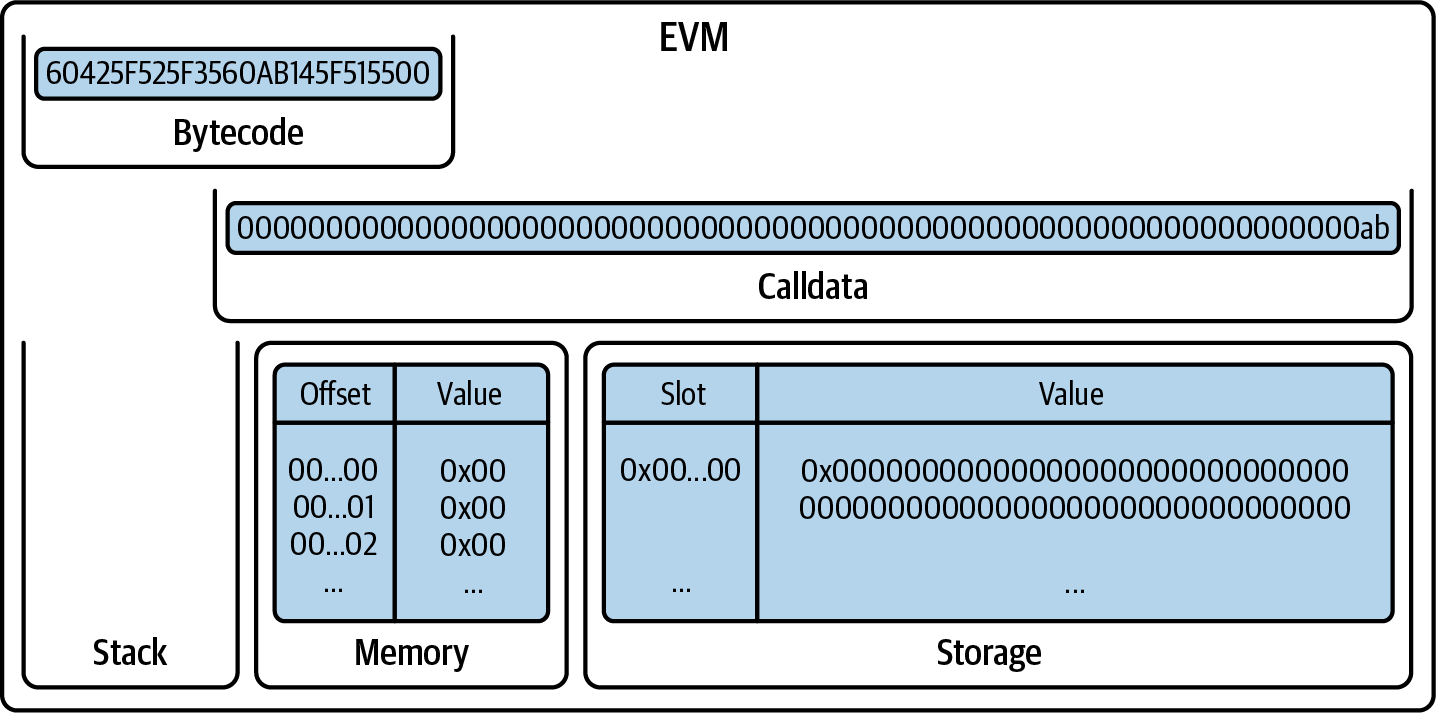

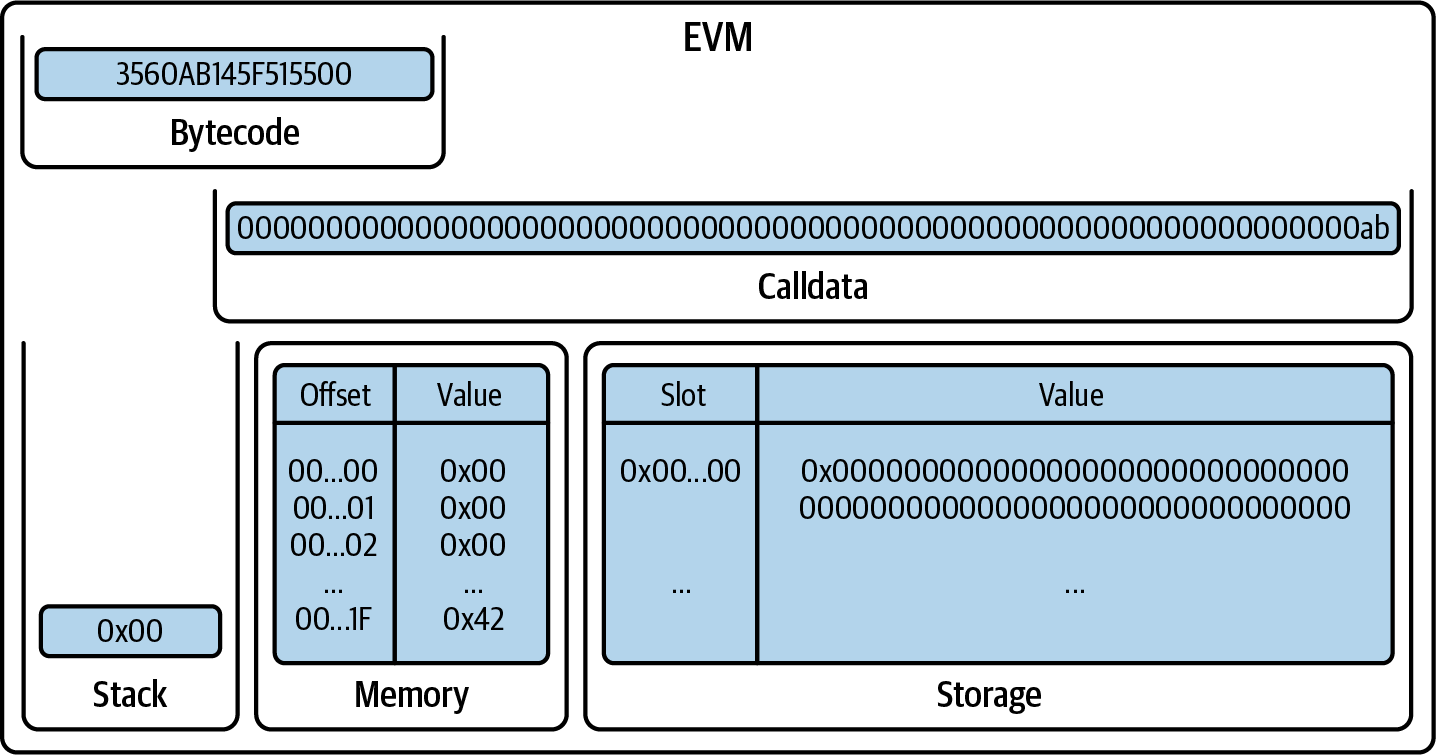

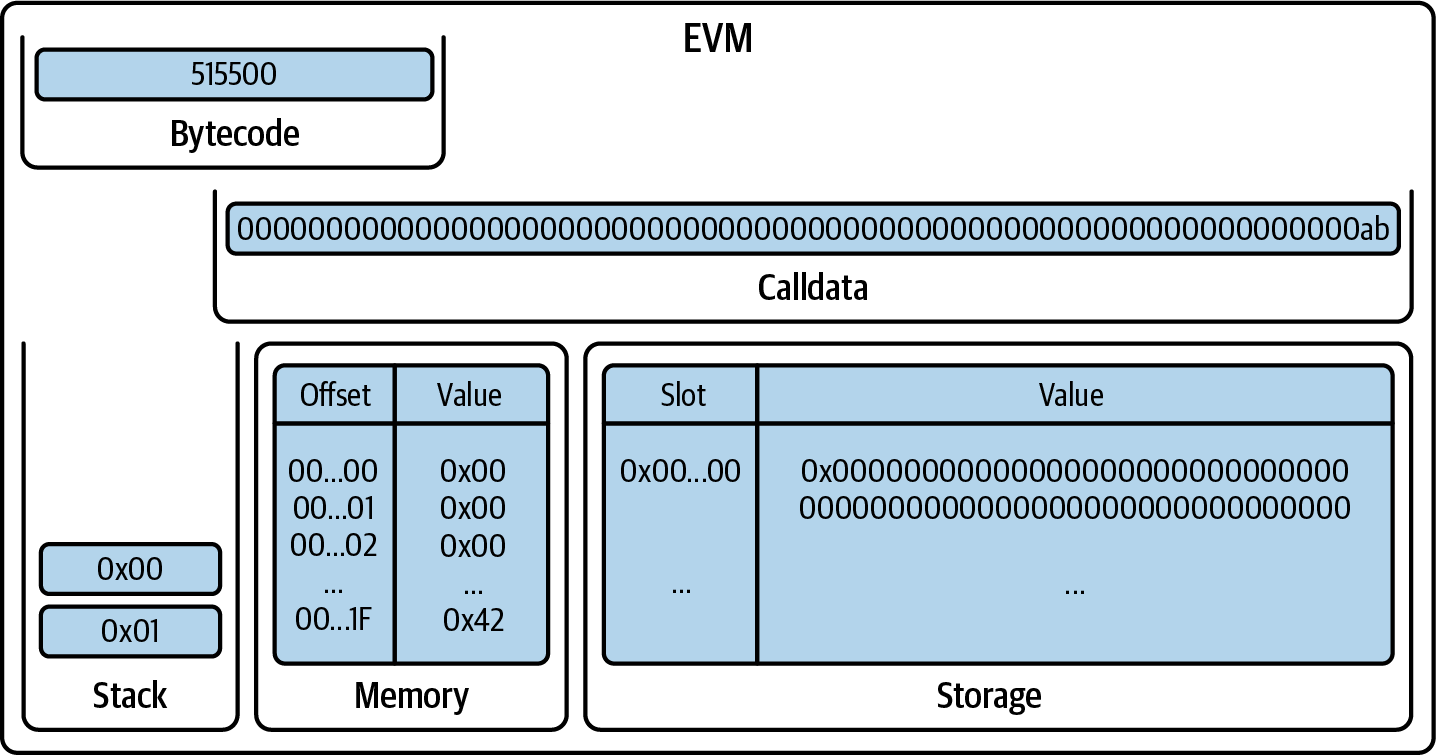

Figure 14-1. EVM architecture and execution context

Comparison with Existing Technology

The term virtual machine is often applied to the virtualization of a real computer, typically by a hypervisor such as VirtualBox or QEMU, or of an entire operating system instance, such as Linux's KVM. These must provide a software abstraction, respectively, of actual hardware and of system calls and other kernel functionality.

The EVM operates in a much more limited domain: it is just a computation engine and as such, provides an abstraction of just computation and storage, similar to the Java virtual machine (JVM) specification, for example. From a high-level viewpoint, the JVM is designed to provide a runtime environment that is agnostic of the underlying host OS or hardware, enabling compatibility across a wide variety of systems. High-level programming languages such as Java or Scala (which use the JVM) or C# (which uses .NET) are compiled into the bytecode instruction set of their respective virtual machines. In the same way, the EVM executes its own bytecode instruction set (described in the next section), which higher-level smart contract programming languages such as Solidity, Vyper, and Yul are compiled into.

The EVM, therefore, has no scheduling capability because execution ordering is organized externally to it: Ethereum clients run through verified block transactions to determine which smart contracts need executing and in which order. In this sense, the Ethereum world computer is single threaded, like JavaScript. Neither does the EVM have any "system interface" handling or "hardware support"—there is no physical machine to interface with. The Ethereum world computer is completely virtual.

What Are Other Blockchains Doing?

The EVM is definitely the most widely used virtual machine in the cryptocurrency space. Most alternative L1 and L2 blockchains use the EVM to maintain compatibility with all the existing tools and frameworks and to attract projects and developers directly from the Ethereum community.

Nevertheless, a bunch of different virtual machines have emerged in recent years: Solana VM, Wasm VM, Cairo VM, and Move VM are probably the most famous and interesting ones, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. They take different approaches to smart contract development:

Custom languages

Some platforms, like Cairo and Move, have created specialized programming languages specifically for writing smart contracts. This is similar to how Ethereum uses Solidity and Vyper for its virtual machine, the EVM.

Standard languages

Others, such as Solana and those using WebAssembly (Wasm), allow developers to write smart contracts with widely used programming languages. For example, these platforms often support Rust for smart contract development.

Another area where these alternative virtual machines differ from the EVM is the parallelization of transactions. We've already said that the EVM processes transactions sequentially, without any kind of parallelization. Some projects took this downside and tried to improve it. For example, both Solana VM and Move VM can handle parallel execution of transactions, even though it's not always possible—that is, when two transactions modify the same piece of storage by interacting with the same contracts, they cannot be executed in parallel.

We must say that these efforts to improve the virtual machine's performance are not being made only outside of Ethereum. In fact, lots of teams are working on breaking the current limits of the EVM by trying to add parallelization and other cool features such as ahead-of-time (AOT) or just-in-time (JIT) compilation from EVM bytecode to native machine code.

The EVM Instruction Set (Bytecode Operations)

The EVM instruction set offers most of the operations you might expect, including:

- Arithmetic and bitwise logic operations

- Execution context inquiries

- Stack, memory, and storage access

- Control flow operations

- Logging, calling, and other operators

In addition to the typical bytecode operations, the EVM has access to account information (e.g., address and balance) and block information (e.g., block number and current gas price).

Let's start our exploration of the EVM in more detail by looking at the available opcodes and what they do. As you might expect, all operands are taken from the stack, and the result (where applicable) is often put back on the top of the stack.

The available opcodes can be divided into the following categories:

Arithmetic operations

The arithmetic opcode instructions include:

ADD //Add the top two stack items

MUL //Multiply the top two stack items

SUB //Subtract the top two stack items

DIV //Integer division

SDIV //Signed integer division

MOD //Modulo (remainder) operation

SMOD //Signed modulo operation

ADDMOD //Addition modulo any number

MULMOD //Multiplication modulo any number

EXP //Exponential operation

SIGNEXTEND //Extend the length of a two's complement signed integer

SHA3 //Compute the Keccak-256 hash of a block of memory

Note that all arithmetic is performed modulo 2256 (unless otherwise noted) and that the zeroth power of zero, 00, is taken to be 1.

Stack operations

Stack, memory, and storage management instructions include:

POP //Remove the top item from the stack

MLOAD //Load a word from memory

MSTORE //Save a word to memory

MSTORE8 //Save a byte to memory

SLOAD //Load a word from storage

SSTORE //Save a word to storage

TLOAD //Load a word from transient storage

TSTORE //Save a word to transient storage

MSIZE //Get the size of the active memory in bytes

PUSH0 //Place value 0 on the stack

PUSHx //Place x byte item on the stack, where x can be any integer from

// 1 to 32 (full word) inclusive

DUPx //Duplicate the x-th stack item, where x can be any integer from

// 1 to 16 inclusive

SWAPx //Exchange 1st and (x+1)-th stack items, where x can be any

// integer from 1 to 16 inclusive

Process-flow operations

Instructions for control flow include:

STOP //Halt execution

JUMP //Set the program counter to any value

JUMPI //Conditionally alter the program counter

PC //Get the value of the program counter (prior to the increment

//corresponding to this instruction)

JUMPDEST //Mark a valid destination for jumps

System operations

Opcodes for the system executing the program include:

LOGx //Append a log record with x topics, where x is any integer

//from 0 to 4 inclusive

CREATE //Create a new account with associated code

CALL //Message-call into another account, i.e., run another

//account's code

CALLCODE //Message-call into this account with another

//account's code

RETURN //Halt execution and return output data

DELEGATECALL //Message-call into this account with an alternative

//account's code, but persisting the current values for

//sender and value

STATICCALL //Static message-call into an account, i.e., it cannot change

//the state of any account

REVERT //Halt execution, reverting state changes but returning

//data and remaining gas

INVALID //The designated invalid instruction

SELFDESTRUCT //Halt execution and, if executed in the same transaction a

//contract was created, register account for deletion. Note

//that its usage is highly discouraged and the opcode is

//considered deprecated

Logic operations

Opcodes for comparisons and bitwise logic include:

LT //Less-than comparison

GT //Greater-than comparison

SLT //Signed less-than comparison

SGT //Signed greater-than comparison

EQ //Equality comparison

ISZERO //Simple NOT operator

AND //Bitwise AND operation

OR //Bitwise OR operation

XOR //Bitwise XOR operation

NOT //Bitwise NOT operation

BYTE //Retrieve a single byte from a full-width 256-bit word

Environmental operations

Opcodes dealing with execution environment information include:

GAS //Get the amount of available gas (after the reduction for

//this instruction)

ADDRESS //Get the address of the currently executing account

BALANCE //Get the account balance of any given account

ORIGIN //Get the address of the EOA that initiated this EVM

//execution

CALLER //Get the address of the caller immediately responsible

//for this execution

CALLVALUE //Get the ether amount deposited by the caller responsible

//for this execution

CALLDATALOAD //Get the input data sent by the caller responsible for

//this execution

CALLDATASIZE //Get the size of the input data

CALLDATACOPY //Copy the input data to memory

CODESIZE //Get the size of code running in the current environment

CODECOPY //Copy the code running in the current environment to

//memory

GASPRICE //Get the gas price specified by the originating

//transaction

EXTCODESIZE //Get the size of an account's code

EXTCODECOPY //Copy an account's code to memory

RETURNDATASIZE //Get the size of the output data from the previous call

//in the current environment

RETURNDATACOPY //Copy data output from the previous call to memory

Block operations

Opcodes for accessing information on the current block include:

BLOCKHASH //Get the hash of one of the 256 most recently completed

//blocks

COINBASE //Get the block's beneficiary address for the block reward

TIMESTAMP //Get the block's timestamp

NUMBER //Get the block's number

PREVRANDAO //Get the previous block's RANDAO mix. This opcode replaces the

//DIFFICULTY one since The Merge hard fork.

GASLIMIT //Get the block's gas limit

Ethereum State

The job of the EVM is to update the Ethereum state by computing valid state transitions as a result of smart contract code execution, as defined by the Ethereum protocol. This aspect leads to the description of Ethereum as a transaction-based state machine, which reflects the fact that external actors (i.e., account holders and validators) initiate state transitions by creating, accepting, and ordering transactions. It is useful at this point to consider what constitutes the Ethereum state.

At the top level, we have the Ethereum world state. The world state is a mapping of Ethereum addresses (160-bit values) to accounts. At the lower level, each Ethereum address represents an account comprising an ether balance (stored as the number of wei owned by the account), a nonce (representing the number of transactions successfully sent from this account if it is an EOA or the number of contracts created by it if it is a contract account), the account's storage (which is a permanent data store used only by smart contracts), and the account's program code (again, only if the account is a smart contract account). Traditionally, an EOA would always have no code and an empty storage. However, EIP-7702 (activated in the Pectra upgrade in May 2025) changes this assumption by allowing EOAs to delegate code execution to smart contracts. When an EOA opts into delegation, its code field is set to a 23-byte delegation designation with the format 0xef0100 || address, where address is the 20-byte address of the target contract. The 0xef byte is a banned opcode per EIP-3541, ensuring this designation cannot be confused with deployable contract code. When the EVM encounters a call to a delegated EOA, it loads and executes the code from the target address in the context of the EOA. This means EXTCODESIZE on a delegated EOA returns 23 (the size of the delegation designation), while CODESIZE executed within the delegated code returns the size of the target contract's code. The EOA can also use storage when executing delegated code, though the protocol recommends using ERC-7201 namespaced storage layouts to prevent collisions when migrating between delegate contracts. Importantly, delegated EOAs can still originate transactions—they remain EOAs that can sign and send transactions, but now with smart contract capabilities. The delegation can be cleared by delegating to the zero address (0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000).

When a transaction results in smart contract code execution, an EVM is instantiated with all the information required in relation to the current block being created and the specific transaction being processed. In particular, the EVM's program code ROM is loaded with the code of the contract account being called, the program counter is set to zero, the storage is loaded from the contract account's storage, the memory is set to all zeros, and all the block and environment variables are set. A key variable is the gas supply for this execution, which is set to the amount of gas paid for by the sender at the start of the transaction (see "Gas Accounting During Execution" for more details). As code execution progresses, the gas supply is reduced according to the gas cost of the executed operations. If at any point the gas supply is less than zero, we get an out-of-gas (OOG) exception: execution immediately halts, and the transaction is abandoned. No changes to the Ethereum state are applied, except for the sender's nonce being incremented and their ether balance going down to pay the block's beneficiary for the resources used to execute the code to the halting point. At this point, you can think of the EVM as running on a sandboxed copy of the Ethereum world state, with this sandboxed version being discarded completely if execution cannot complete for whatever reason. However, if execution does complete successfully, then the real-world state is updated to match the sandboxed version, including any changes to the called contract's storage data, any new contracts created, and any ether balance transfers that were initiated.

Code execution is a recursive process. A contract can call other contracts, with each call resulting in another EVM being instantiated around the new target of the call. Each instantiation has its sandbox world state initialized from the sandbox of the EVM at the level above. Each instantiation (context) is also given a specified amount of gas for its gas supply (not exceeding the amount of gas remaining in the level above, of course) and so may itself halt with an exception due to being given too little gas to complete its execution. Again, in such cases, the sandbox state is discarded, and execution returns to the EVM at the level above.

Ethereum Stateless

Even though at the time of writing (June 2025), all Ethereum nodes have to compute and maintain the last state—that is, what we previously called the world state—in order to be able to check the correctness of every new block by reexecuting all the transactions it contains, there are plans to get rid of that, at least partially.

The idea is to have a restricted set of actors, such as searchers and builders, that still need to get access to the state to create and publish new blocks, while all other nodes can cryptographically verify those blocks without it. This is called statelessness.

Statelessness is still far in the future of the Ethereum roadmap because it needs some modifications to the core protocol:

Enshrined proposer-builder separation (ePBS)

Separating the work of creating a block by filling it with transactions from the work of proposing it to the P2P network. The first is done by heavily specialized entities called searchers and builders that are able to create super-optimized blocks, while the second is done by Ethereum validator nodes. This is already a reality on mainnet, even though it's still not enshrined in the protocol. In fact, the majority of Ethereum blocks are already being built by a very small set of big builders.

Verkle trees

A replacement of the data structure that Ethereum currently uses to store the state: the Merkle-Patricia trie. This reduces by a lot the size of the cryptographical proof needed to verify the correctness of the state and makes verifying it faster than the legacy Merkle-Patricia trie.

Note

Other hash-based binary trees are being tested to possibly replace Verkle trees. The core idea is just to have a data structure for the state that makes it possible to create small proofs that are quick and easy to verify.

The combination of these two upgrades can lead to a scenario where only the big entities with more powerful hardware that want to create blocks need to store and access the full state. Together with new blocks, they will create a cryptographic witness: the minimal set of data that proves the new state has been computed correctly based on the transactions they included into the blocks.

All other nodes (including validator nodes) store only the state root, which is the hash of the entire state. When they receive a new block, they use the related witness to verify its correctness.

This makes running an Ethereum node very lightweight since you don't have to store the full state and you don't even need to reexecute all the transactions (inside the EVM), but you are still able to verify that everything is correct so that you don't need to trust third parties. You could even run a node on your smartphone…

Even though research advances quickly, we are probably still a few years away from having statelessness on mainnet.

Merkle-Patricia Trie

Right now, the Ethereum state is stored using a very peculiar data structure called a modified Merkle-Patricia trie. We briefly mentioned the Merkle-Patricia tree (we'll call it MPT) in the previous section, but it's very important to understand how it works and why as well as how it's used by Ethereum as the way to store the state (and not only that…) because the same reasoning applies to Verkle tries. Before diving into MPTs, you need to know about Merkle trees because they represent the foundation on which MPTs are built.

Merkle trees

Merkle trees are a very old data structure, invented by Ralph Merkle in 1988 in an attempt to construct better digital signatures. They are very efficient when you need to be able to verify that some data exists in a database and it has not been tampered with without needing to send the entire database to prove it.

It's quite easy to create a Merkle tree starting from a collection of data. You need to separate the data into several chunks; then, you hash those chunks together and repeat this last step in a recursive way until you get only one final chunk. That chunk represents the Merkle root: a sort of digital fingerprint of all the data used to create the tree.

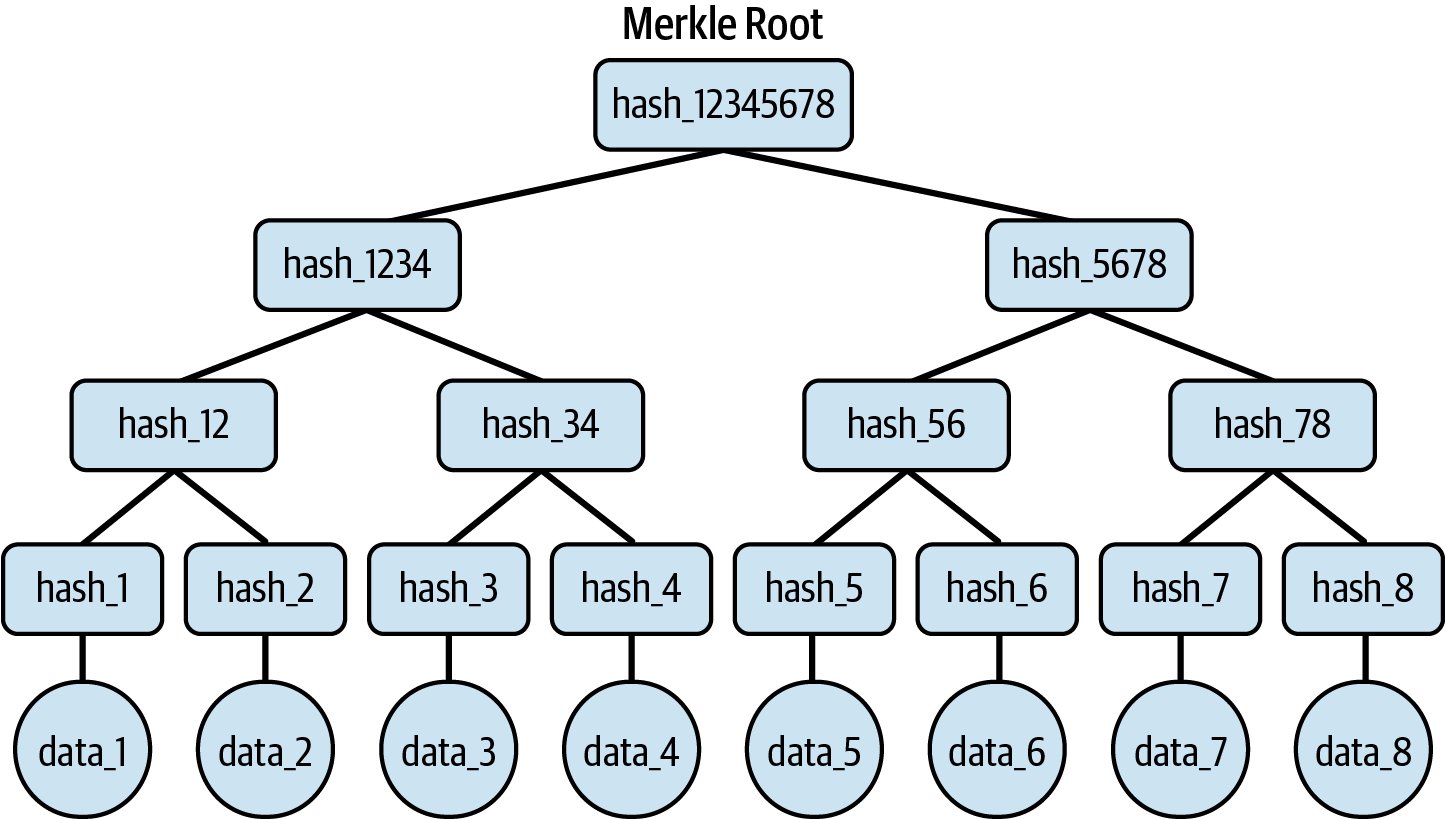

Let's create a binary Merkle tree—the simplest form of a Merkle tree—from scratch so that you can familiarize yourself with it a bit more. We start with eight chunks of data—you could think of them as different words in the English language. We hash each chunk using a specific hash function—Ethereum uses the Keccak-256 hash function, as already mentioned in Chapter 4—obtaining the leaves of the Merkle tree, represented in Figure 14-2 as hash_1, hash_2, and so on. Then, we concatenate each couple of leaves and hash them again, creating hash_12, hash_34, and so on. We repeat this process of concatenating and hashing another two times until we get to a single, final result, which represents our Merkle root: hash_12345678.

Figure 14-2. A binary merkle tree

Now, you may be asking why we need a Merkle tree to store the data. Isn't it more complicated than just storing each chunk in a classical database?

The answer is yes, it's much more complex than storing every chunk in a key-value or SQL database. The only reason we use these kinds of data structures is because they are really efficient at providing a cheap cryptographic proof that any one of the chunks is present in the entire collection of data and has not been manipulated. In fact, if we were using a normal database to store data, and we were asked to provide a proof that we have a specific chunk, we would need to publish our entire dataset so that the reader could be sure we're not lying.

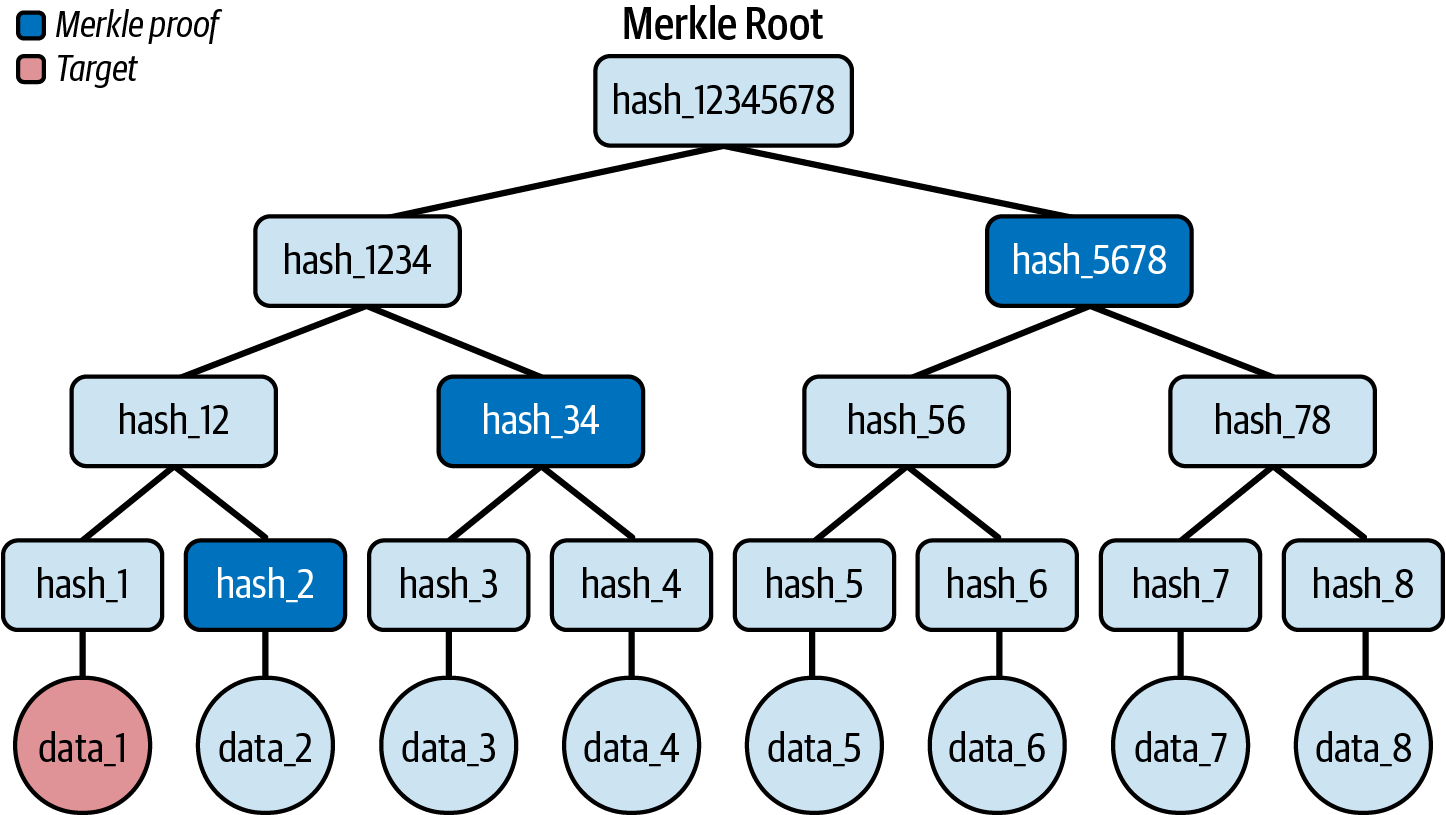

Let's use our previous example to see this in practice. Let's say we want to prove that data_1 is included in the dataset. The naive approach is to provide the entire dataset, starting from data_1 up to data_8: eight items in total. With a Merkle tree, we need to provide only hash_2, hash_34, and hash_5678. Then, anyone can compute on their own the Merkle root and compare it with the one we calculated initially (which is shared publicly). If they match, you can be completely sure that data_1 is part of the initial dataset, as you can see in Figure 14-3.

Figure 14-3. The Merkle proof to verify that data_1 is contained in the tree

Tip

To reconstruct the Merkle tree, you can follow these steps:

- Hash data_1 and get hash_1.

- Concatenate hash_1 with the provided hash_2, hash it, and get hash_12.

- Concatenate hash_12 with the provided hash_34, hash it, and get hash_1234.

- Concatenate hash_1234 with the provided hash_5678, hash it, and get the final Merkle root.

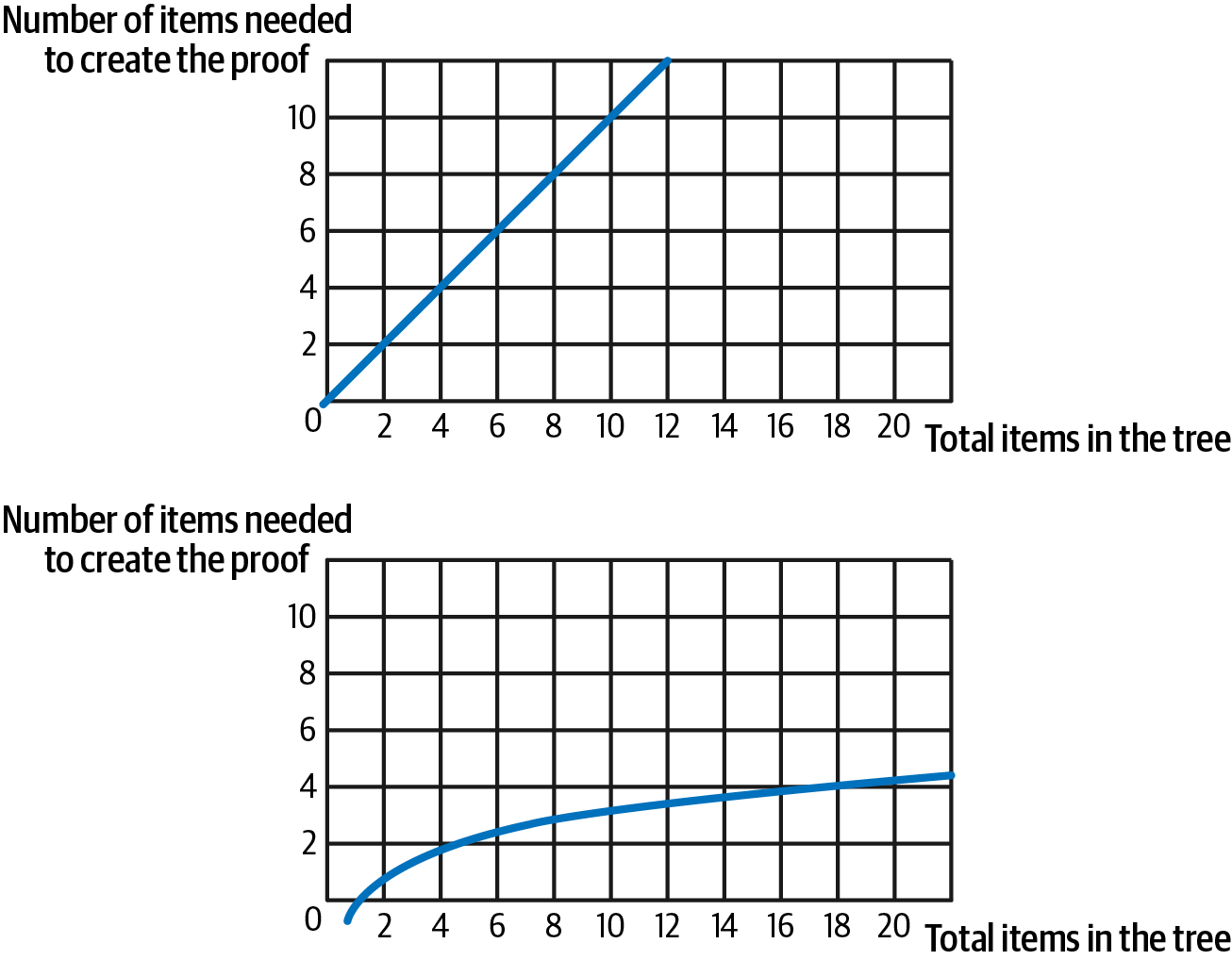

Note that we're using only three items, versus the eight items we would need to use with the naive approach without the Merkle tree. And this is just a toy example—when you have lots of data, the savings are much bigger.

Speaking in mathematical terms, Merkle trees offer O(log(n)) complexity versus linear O(n) of the naive approach, as shown in Figure 14-4.

Figure 14-4. O(n) linear complexity (on the top) versus O(log(n)) complexity (on the bottom)

In the Ethereum world, this means that it's cheaper and easier to provide proofs regarding the balance of an address, the result of a transaction, or the bytecode of a specific smart contract.

Merkle trees in Bitcoin

Bitcoin pioneered the use of Merkle trees in blockchain technology. In fact, every Bitcoin block contains the Merkle root of all transactions included in the same block so that none of them can be modified without modifying the entire block header (compromising the PoW, too).

Merkle-Patricia trie in Ethereum

Ethereum took the same concept and applied it to itself, with some modifications for its specific needs. Merkle trees are perfectly suited for permanent data that never changes, such as Bitcoin transactions. The Ethereum state changes constantly, though, so we need to tweak Merkle trees to still maintain their useful properties while letting us change the data underneath frequently.

This is where the Merkle-Patricia trie enters the scene. The name comes from the union between Merkle trees, Patricia (Practical Algorithm to Retrieve Information Coded in Alphanumeric), and the word trie that originates from retrieval, reminding us what they are optimized for.

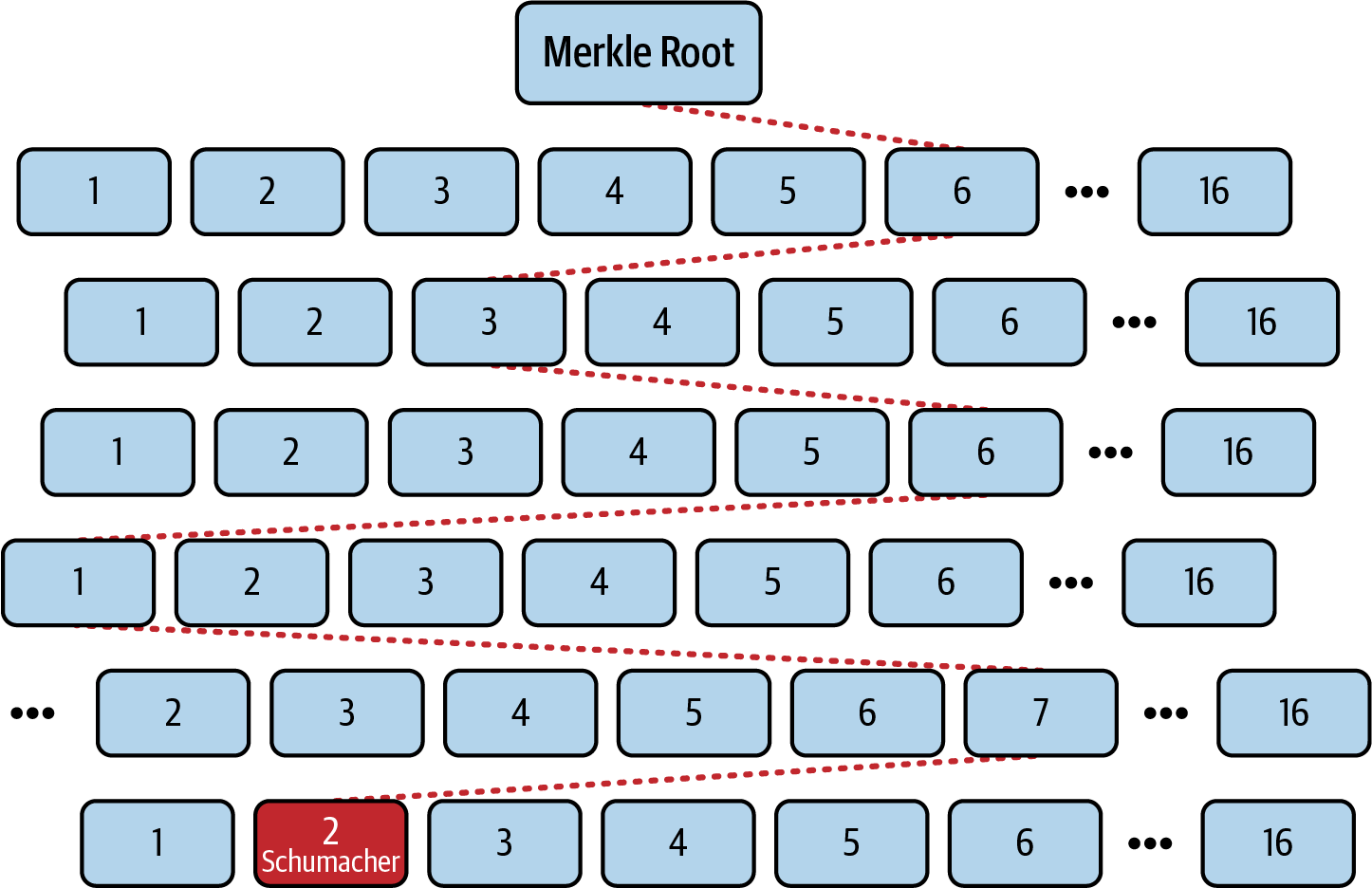

Essentially, Merkle-Patricia tries are modified Merkle trees with 16 children for each node. They are well suited for data like the Ethereum state where you have lots of key-value items (where keys are the addresses and values the account information for each address, such as the balance, the nonce, and the code, if any) because the key itself is encoded in the path you have to follow to reach the correct position in the tree.

Let's say we have the following key-value item we want to store:

car → Schumacher

Car is hex encoded as (0x) 6 3 6 1 7 2, so you would need to take the sixth child starting from the Merkle root, then again down to the third child, repeating this process until you get to the final value where you can read the value associated with that key—Schumacher in this example—as shown in Figure 14-5.

Figure 14-5. Encoding of the key-value item car --> Schumacher into a Merkle-Patricia trie

In particular, Ethereum uses four Merkle-Patricia tries:

State trie

To store the entire state

Transaction trie

To store all transactions included into a block

Receipt trie

To store the results of all the transactions included into a block

Storage trie

To store smart contract data

Every Ethereum block header contains the state, transaction, and receipt trie Merkle root, while every account (contained in the state trie) stores its own storage trie Merkle root.

A Deep Dive into the Components of the EVM

In this section, we'll take a closer look at how each component of the EVM works. Finally, we'll examine a real-world example to see everything in action.

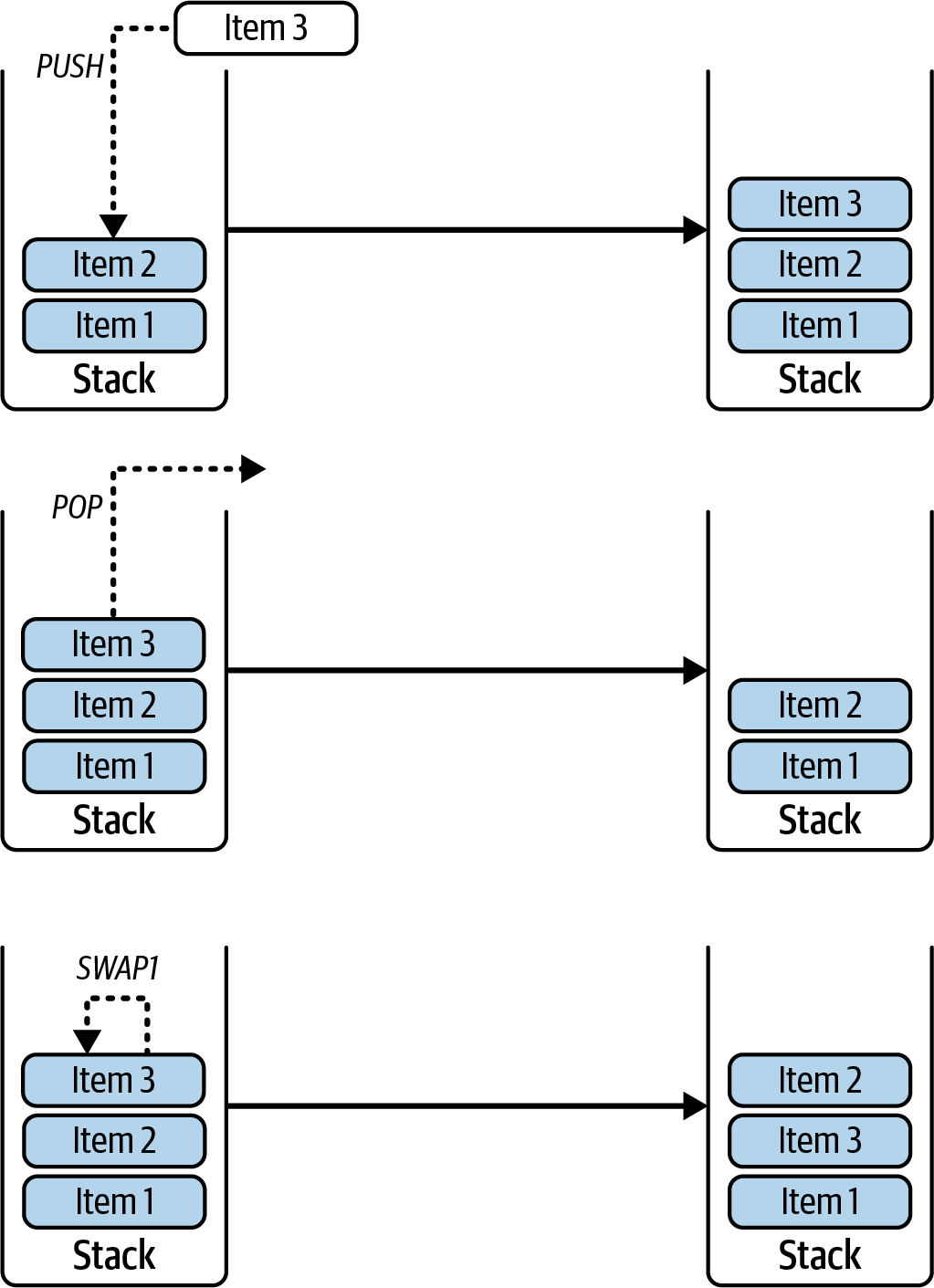

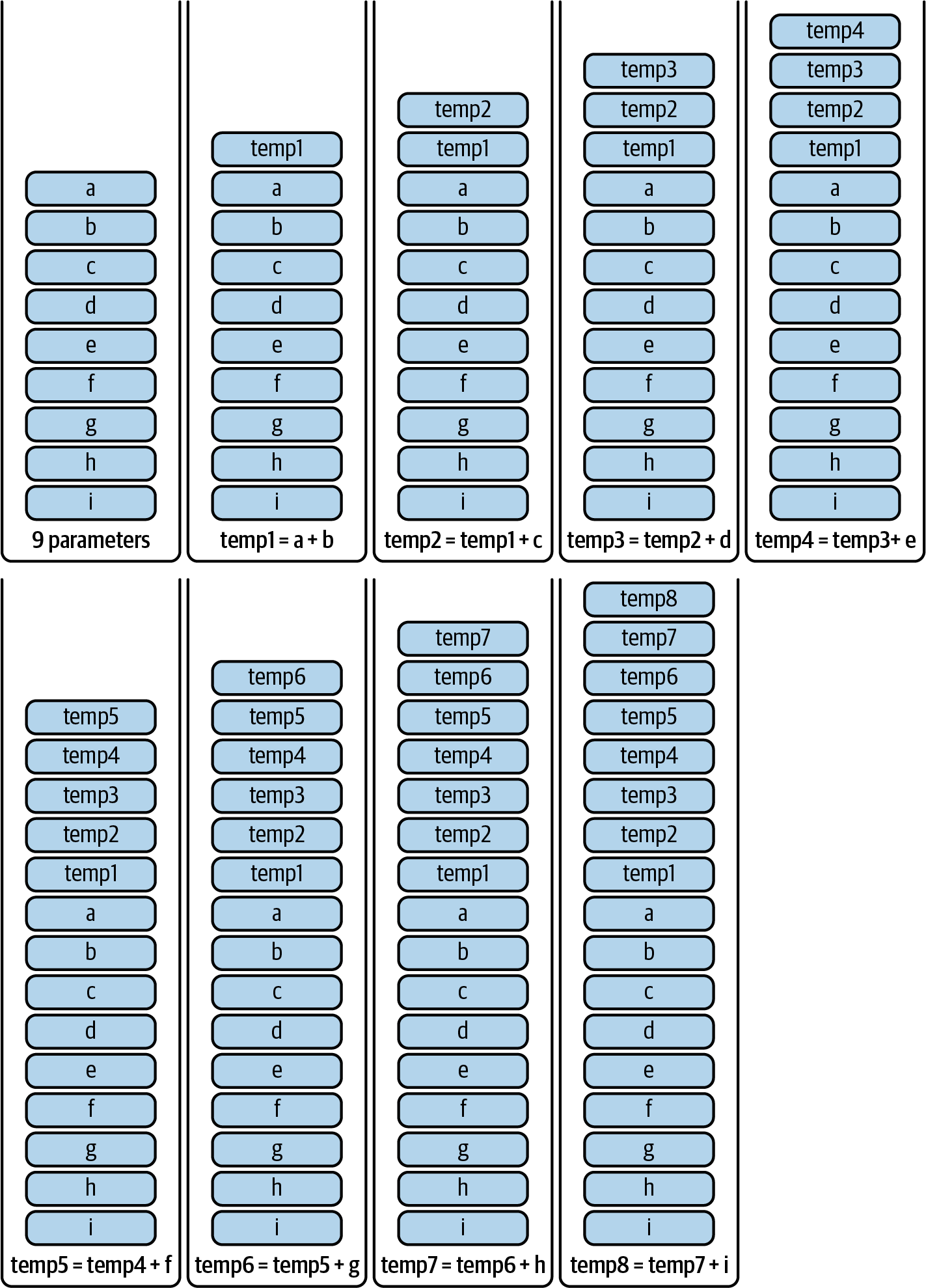

Stack

The stack is a very simple data structure that follows a last in, first out (LIFO) order to perform operations, where every item is a 32-byte object. It can host up to 1,024 items at the same time.

The EVM can push and pop items into and from the stack through different kinds of opcodes, and it can manipulate the order of its elements, as you can see in Figure 14-6.

Figure 14-6. The EVM stack follows a LIFO order of operations

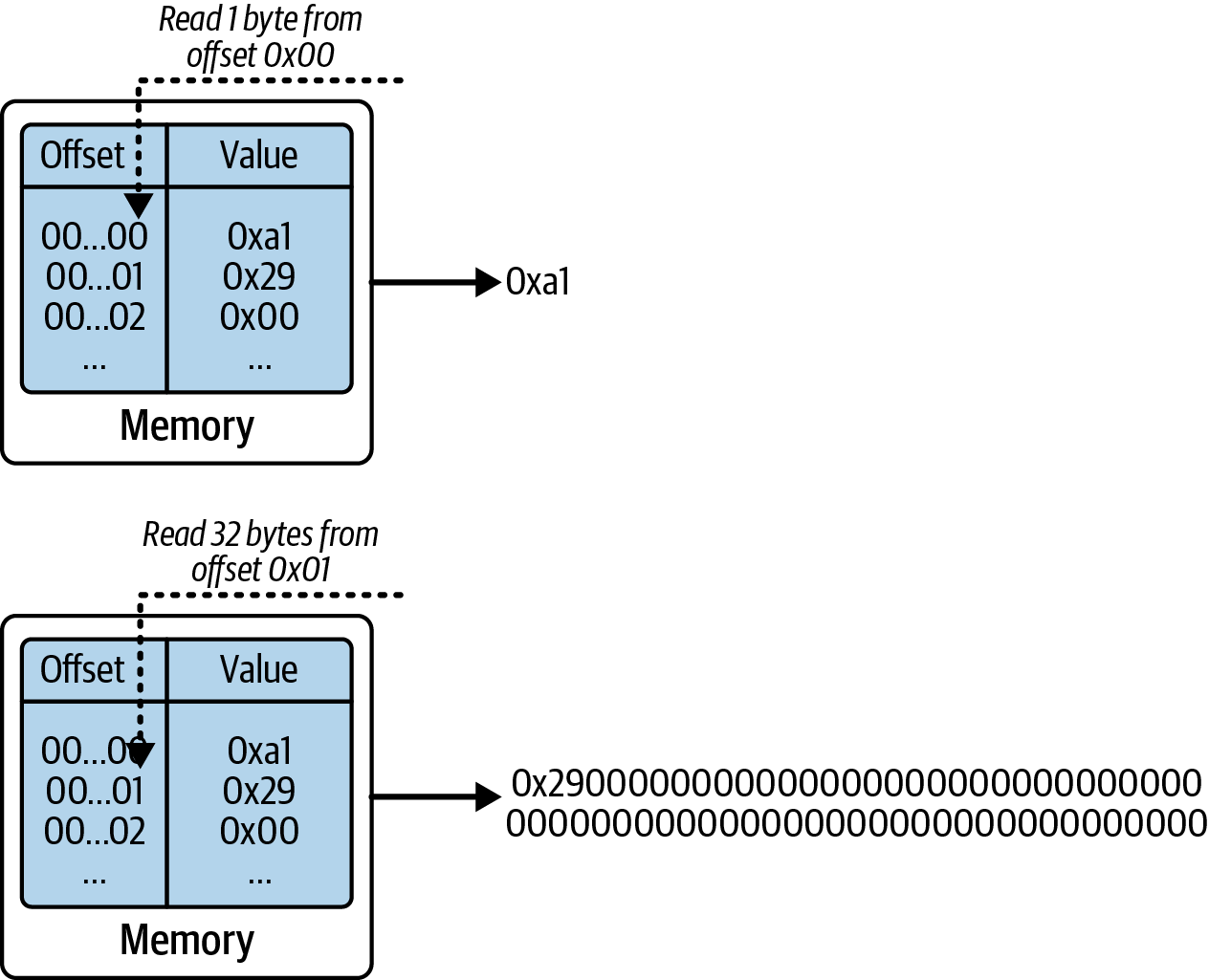

Memory

The EVM memory is a byte-addressable data structure: essentially a very long array of bytes. In fact, every byte in the memory is accessible using a 32-byte (256-bit) key, which means it can contain up to 2256 bytes. It's volatile—that is, it's deleted after the execution ends—and it's always initialized to 0.

Even though it's possible to read and write single bytes to and from the memory, most operations require reading or writing bigger chunks of data, usually 32-byte chunks, as shown in Figure 14-7.

Figure 14-7. EVM memory is a volatile, byte-addressable data structure

Note

Technically, you cannot read a single byte from the EVM. You can only read an entire 32-byte word. To achieve the same result as reading a single byte, the EVM needs to load the entire word that contains that byte and then "cut" it in order to return only the selected byte.

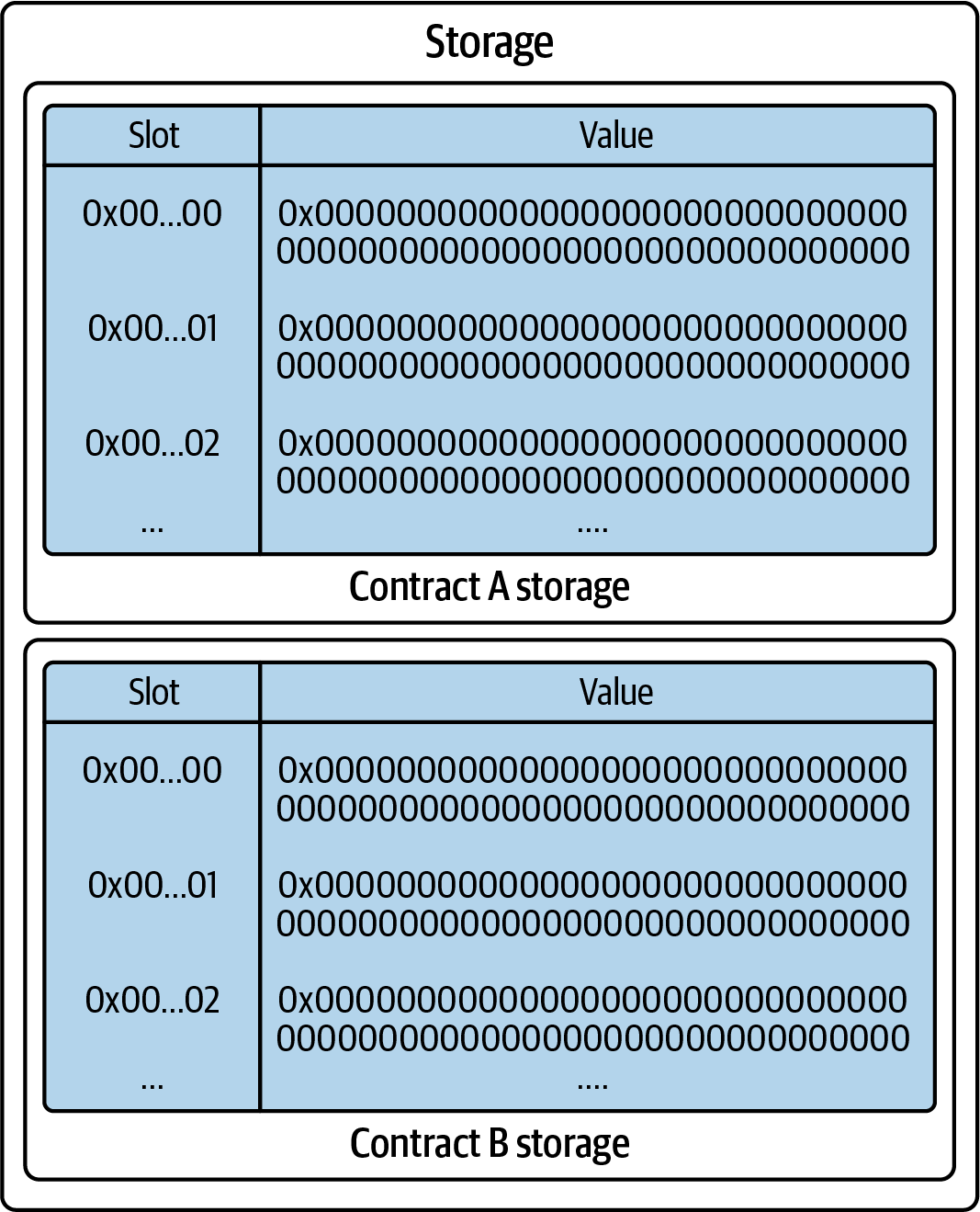

Storage

The EVM storage is a key-value data structure where keys (most often called slots) and values are each 32 bytes long. This is the persistent memory of every smart contract: all values saved on it are kept indefinitely across different transactions and blocks. Each smart contract can only access and modify its own storage, and if you try to access a slot that doesn't contain any values, it will always return the value 0 without throwing any errors. Figure 14-8 shows a very basic representation of two contracts' storage.

Figure 14-8. The EVM storage is a permanent memory with a key-value data structure

There is also the transient storage, added with EIP-1153, which behaves in the same way as the normal storage, with the only difference being that it's completely discarded after the execution of the transaction. For this reason, it's much cheaper to use than normal storage.

Calldata

Calldata is an immutable data structure that always contains the bytes sent as input to the next call frame (i.e., a sandbox EVM environment). For example, in a contract-creation transaction, the calldata contains the bytecode of the contract that is going to be deployed. It can also be empty, such as in simple ETH transfers.

Let's Put Everything Together with a Concrete Example

You are executing a transaction that works on contract A, and you have the following EVM bytecode: 60425F525F3560AB145F515500.

You also have an initial calldata:

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000ab

Let's represent the EVM bytecode in a human-readable format:

[00] PUSH1 42

[02] PUSH0

[03] MSTORE

[04] PUSH0

[05] CALLDATALOAD

[06] PUSH1 AB

[08] EQ

[09] PUSH0

[0a] MLOAD

[0b] SSTORE

[0c] STOP

Note

Each EVM opcode is identified by a unique 1-byte value (ranging from 0x00 to 0xFF). For example, 0x60 is the PUSH1 opcode, 0x5F the PUSH0, and so on. For a comprehensive list of all opcodes and their hexadecimal representations, refer to EVM codes.

Let's see how the EVM executes these opcodes and how the stack, the memory, and the storage are manipulated. Figure 14-9 shows the initial state of the EVM.

Figure 14-9. Initial EVM state

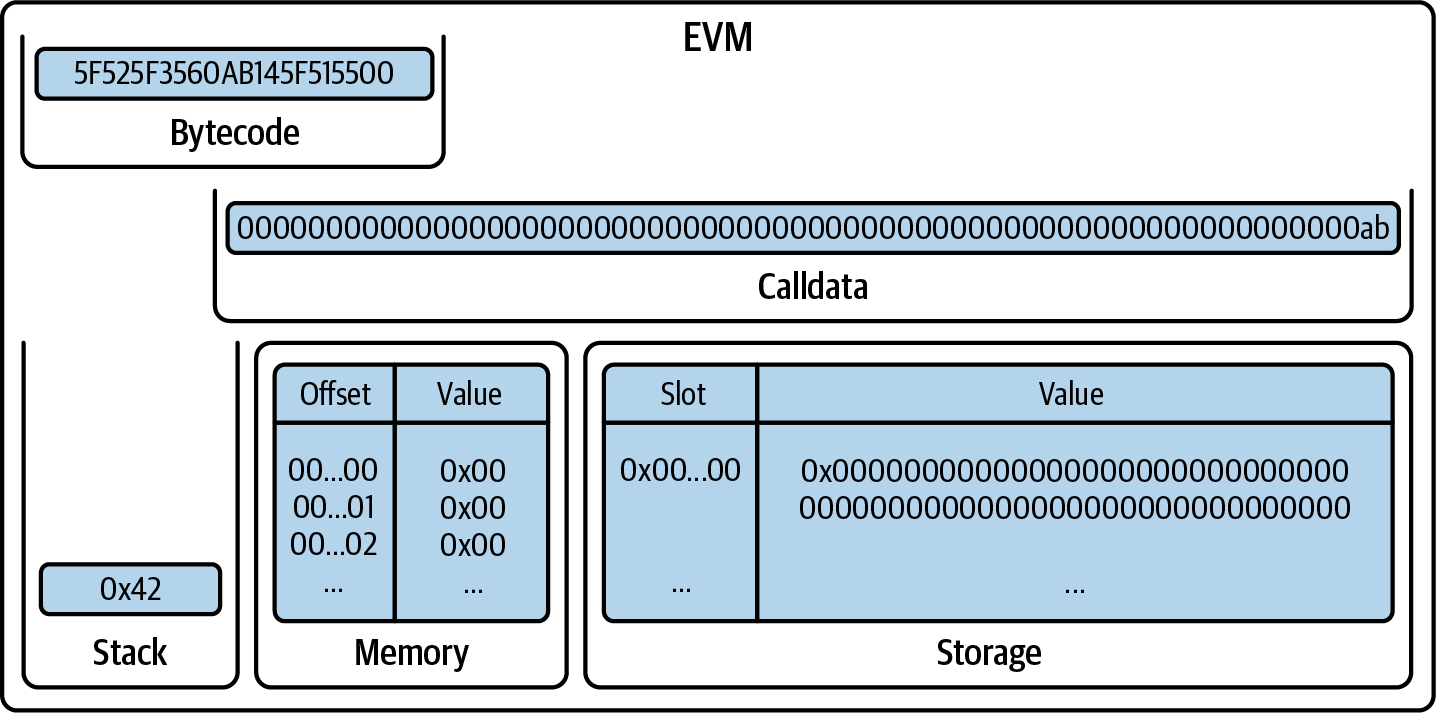

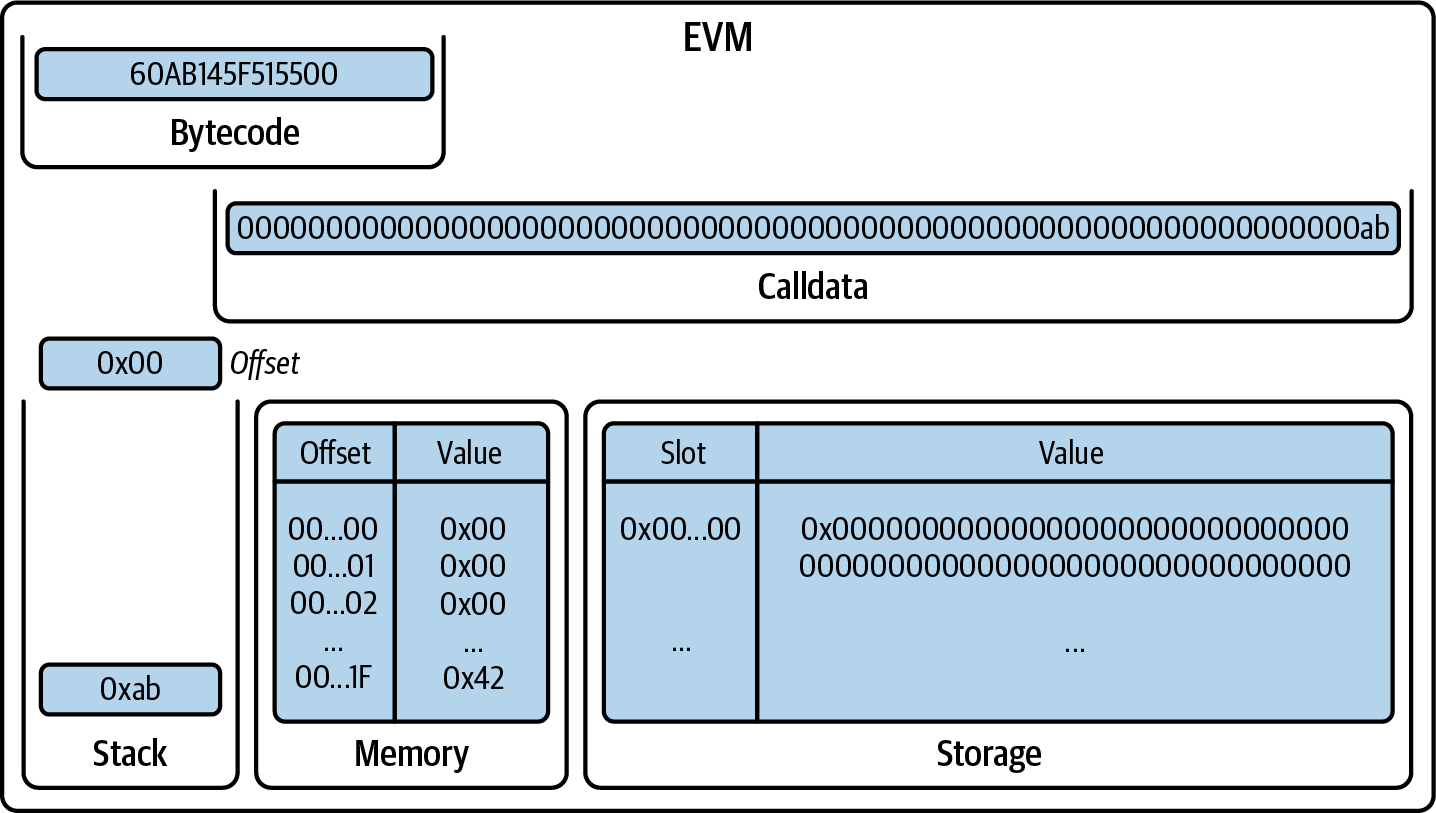

The first opcode pushes 0x42 onto the stack (Figure 14-10). Note that all push opcodes take their data (to be pushed) from the next available bytes in the bytecode itself.

Figure 14-10. EVM after PUSH1 0x42

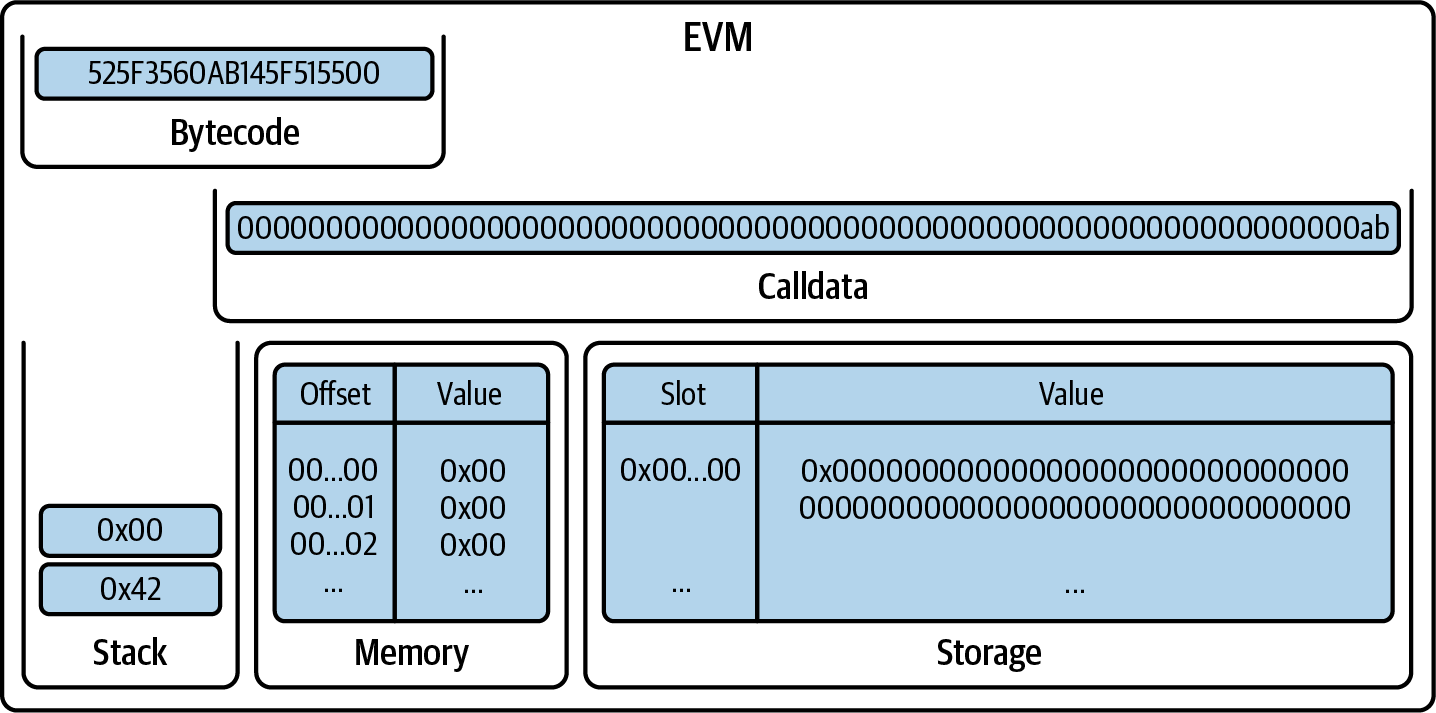

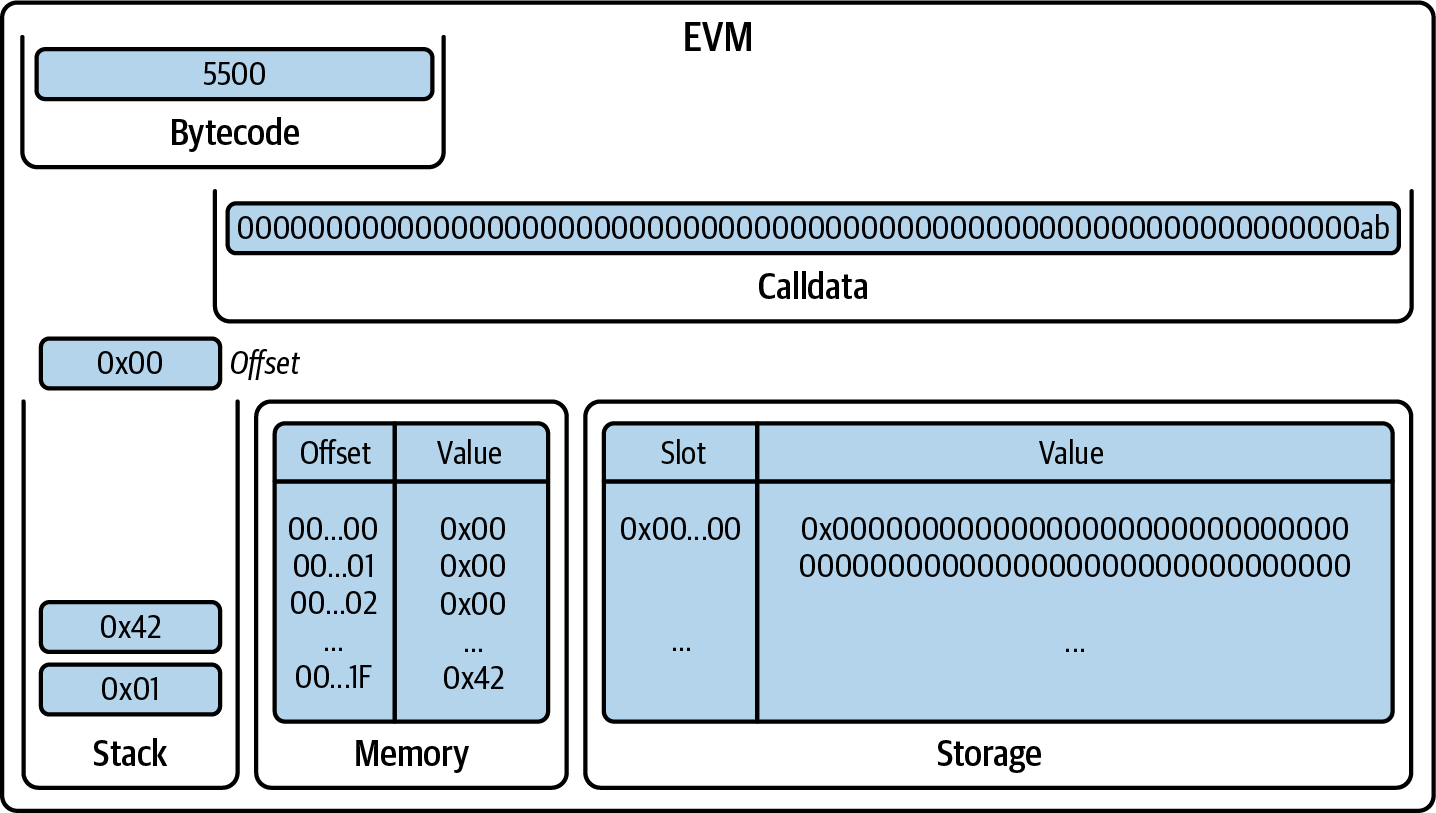

Next, PUSH0 pushes 0x00 onto the stack (Figure 14-11).

Figure 14-11. EVM after PUSH0

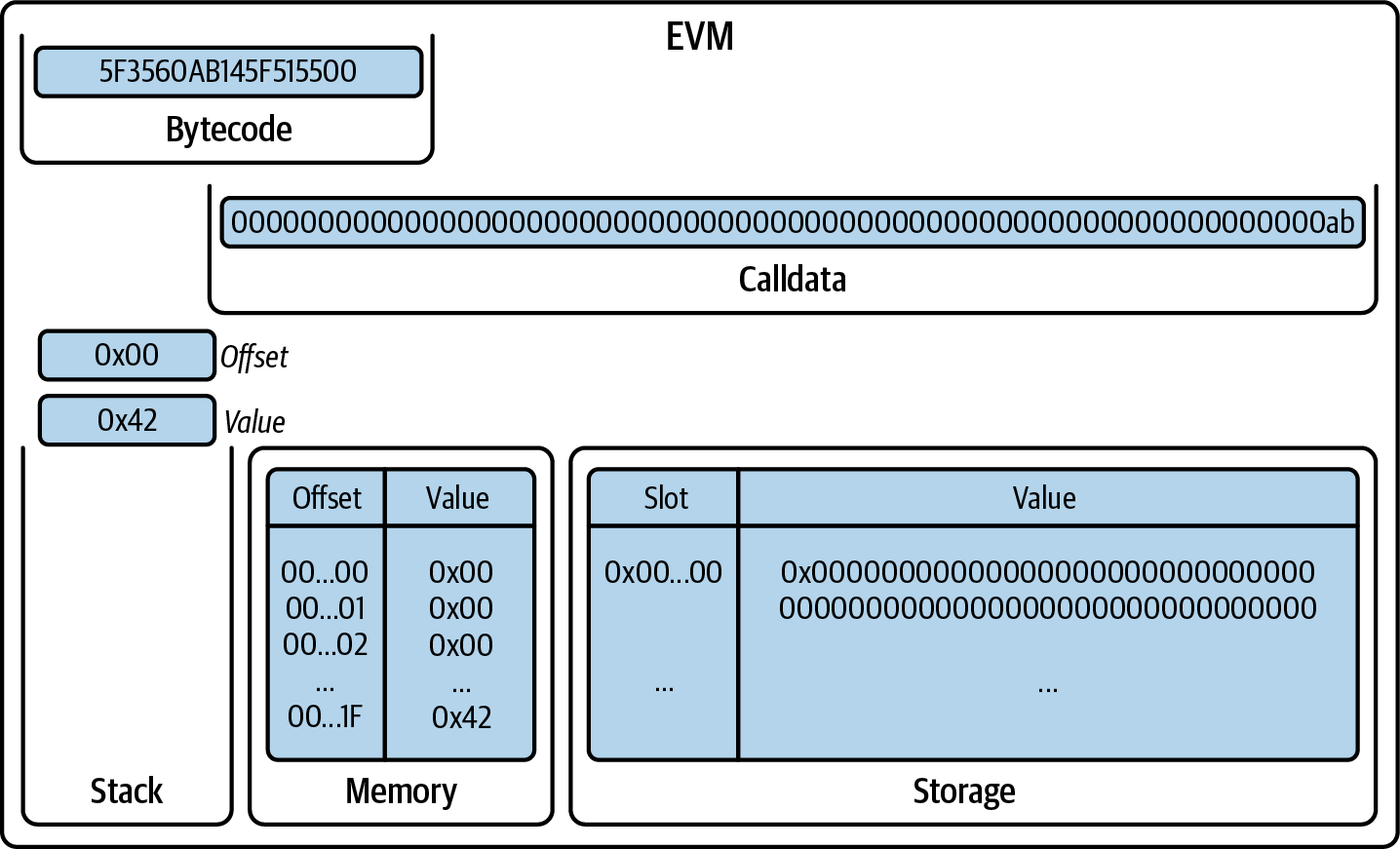

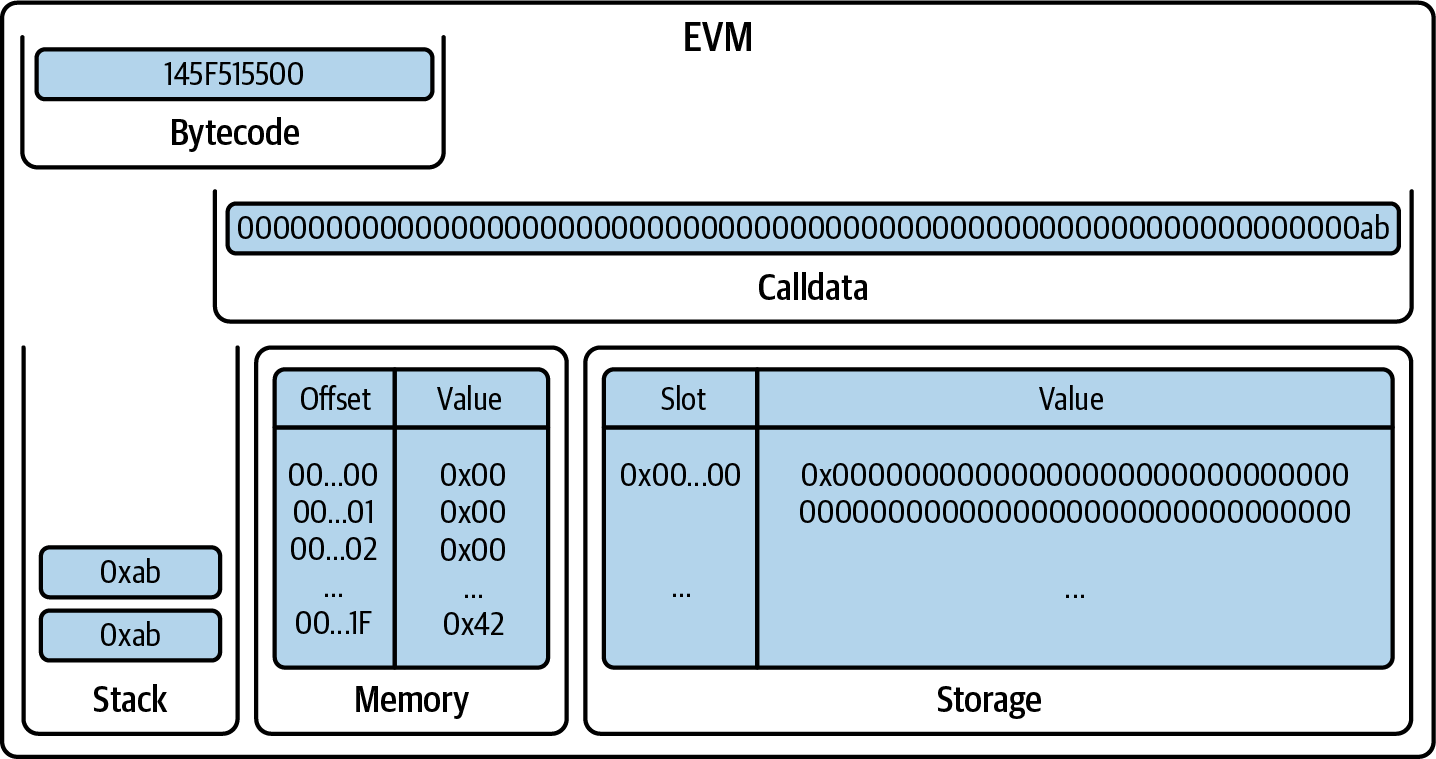

MSTORE pops two items from the stack, interpreting the first one as the offset (in bytes) and the second one as the value to write in the memory, starting at that offset. Note that there are lots of leading zeros in the memory (31 bytes, equal to zero) before the byte 0x42. This is correct because every value in the stack is a 32-byte value. Most of the time, we can ignore leading zeros while writing (in Figure 14-12, you can see the item 0x42), but you should always remember that they are 32-byte values.

Figure 14-12. EVM after MSTORE

Then, we again have a PUSH0 that pushes 0x00 onto the stack (Figure 14-13).

Figure 14-13. EVM after PUSH0

CALLDATALOAD takes one element from the stack, interpreted as an offset, and returns the 32-byte value in the calldata starting at that offset, then pushes it onto the stack. Here, it's returning 0xab (note that we can ignore all the leading zeros as they are not significant), as shown in Figure 14-14.

Figure 14-14. EVM after CALLDATALOAD

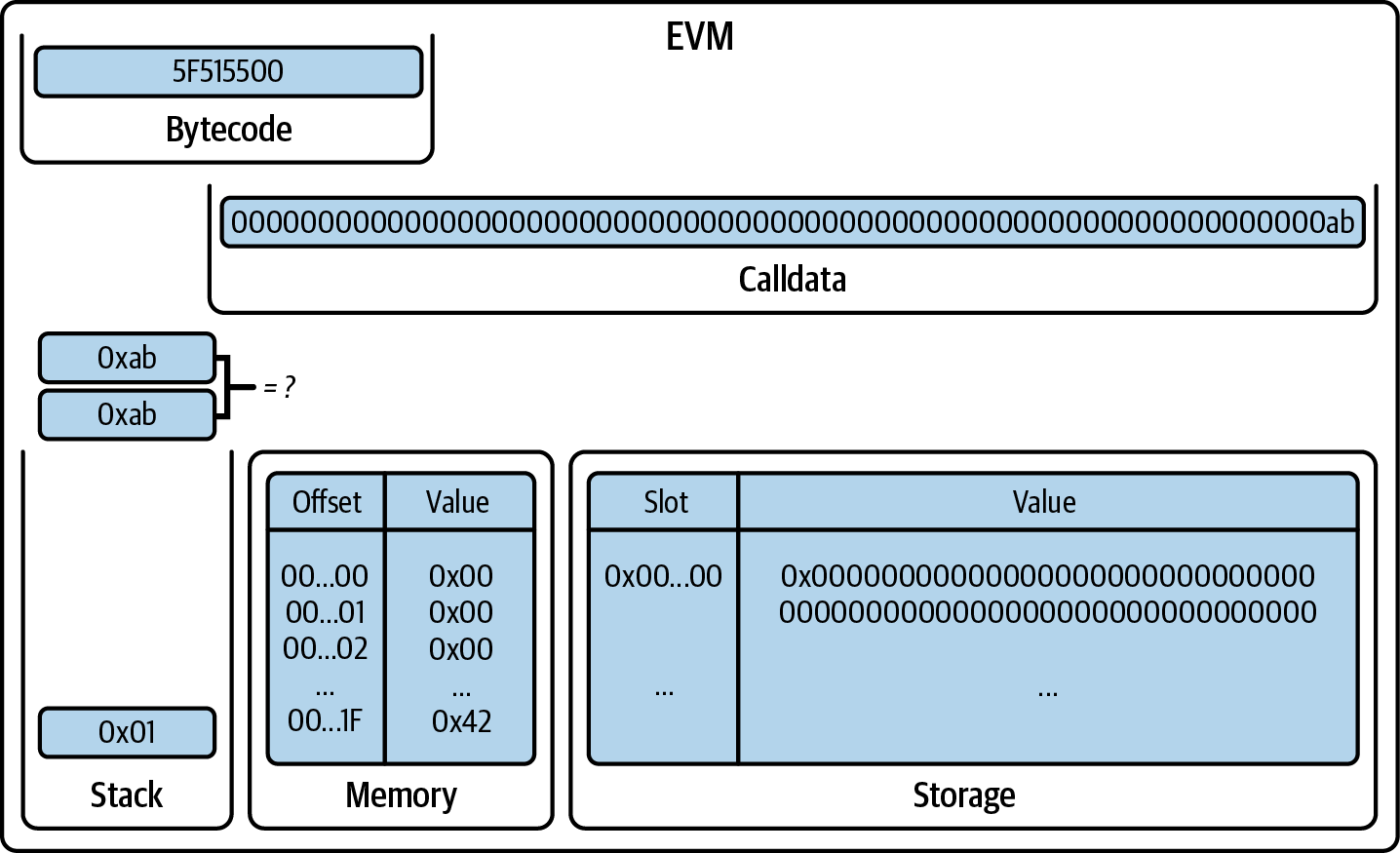

PUSH1 pushes 0xab onto the stack (Figure 14-15).

Figure 14-15. EVM after PUSH1 0xab

EQ pops two items from the stack, compares them, and returns 1 if they are equal, 0 otherwise. In this example, it returns 0x01 since the two values are equal, as shown in Figure 14-16.

Figure 14-16. EVM after EQ

Again, a PUSH0 pushes 0x00 onto the stack (Figure 14-17).

Figure 14-17. EVM after PUSH0

MLOAD takes one element from the stack, interpreting it as the offset, and reads 32 bytes in the memory, starting at that offset, then pushes the result onto the stack (Figure 14-18).

Figure 14-18. EVM after MLOAD

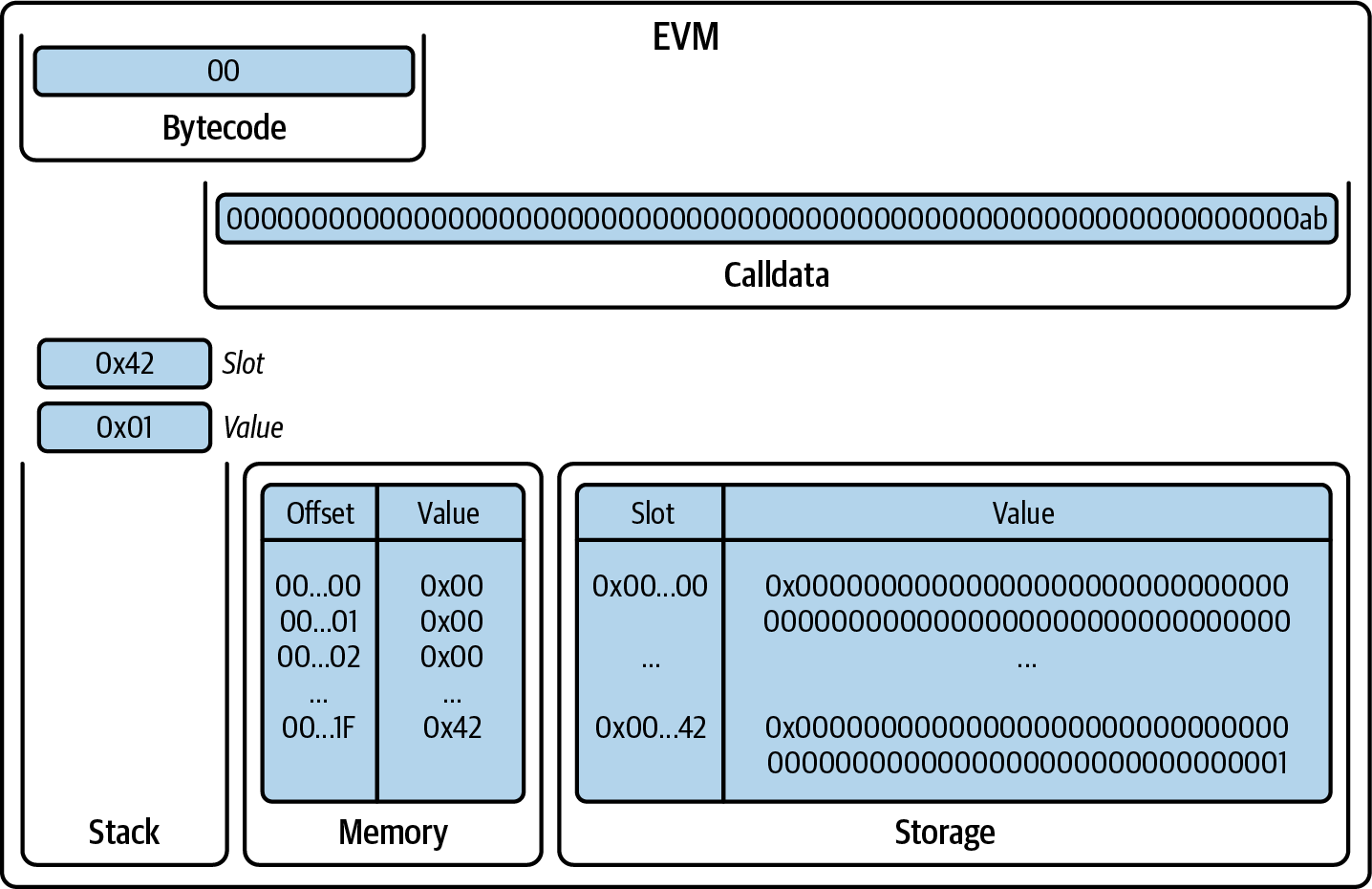

Now, the SSTORE pops two items from the stack, interpreting the first one as the slot and the second one as the value to be saved in the contract's storage at that slot number, as shown in Figure 14-19.

Figure 14-19. EVM after SSTORE

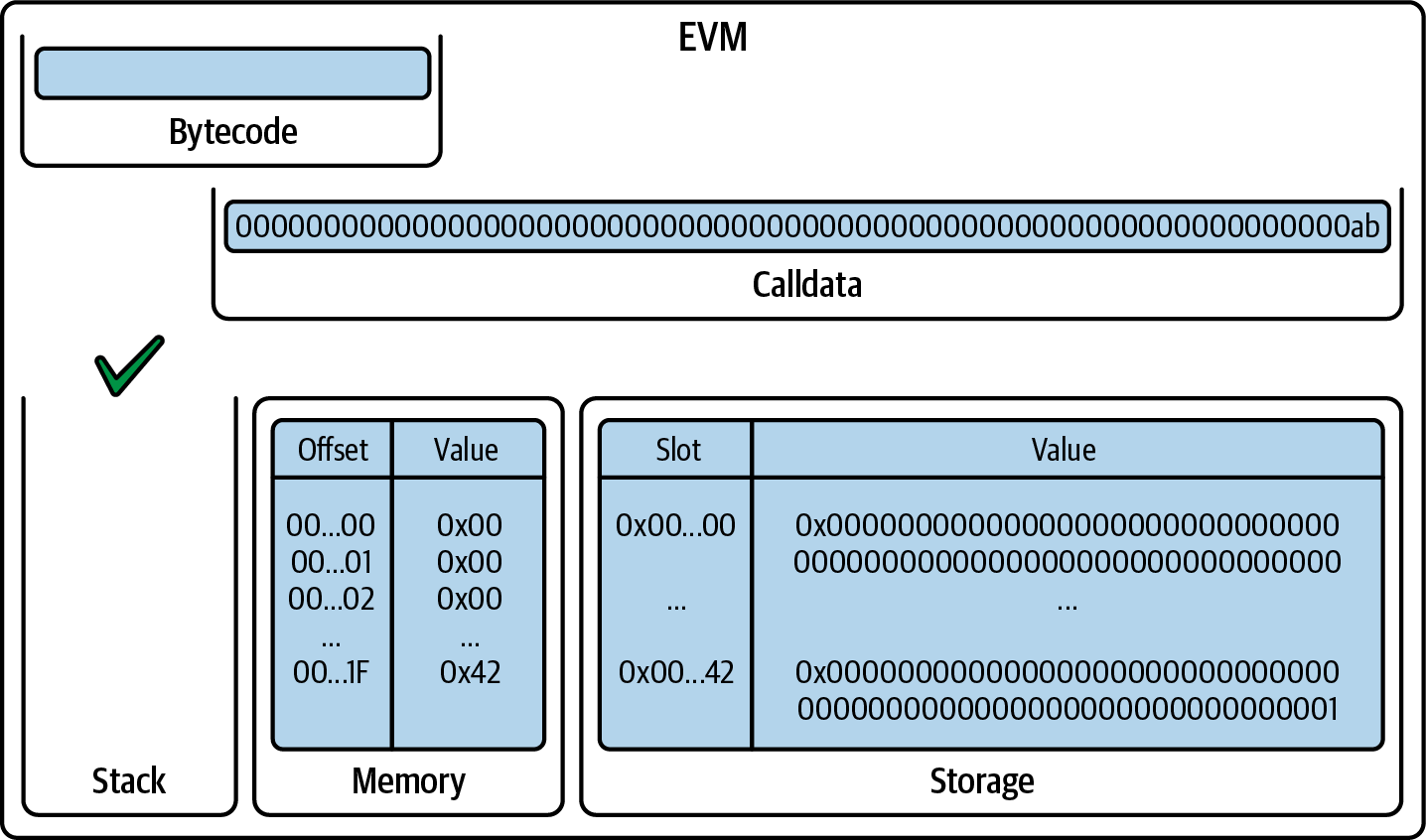

Finally, we have the STOP opcode that halts the execution, and the EVM returns successfully, as you can see in Figure 14-20.

Figure 14-20. EVM after STOP

Tip

In the previous example, we used the opcode PUSH0. It's important to say that not all EVM-compatible blockchains have integrated this opcode, so be aware of that when deploying a cross-chain contract. EVM Diff is a very cool website that shows all these subtle differences for EVM-compatible chains.

Compiling Solidity to EVM Bytecode

We've already explored Solidity in Chapter 7. Now, we're going to see how it's compiled down into EVM bytecode that can be interpreted by the EVM.

Compiling a Solidity source file to EVM bytecode can be accomplished via several methods. In Chapter 2, we used the online Remix compiler. In this chapter, we will use the solc executable at the command line. To install Solidity on your computer, follow the steps.

For a list of options, run the following command:

$ solc --help

Generating the raw opcode stream of a Solidity source file is easily achieved with the --opcodes command-line option. This opcode stream leaves out some information (the --asm option produces the full information), but it is sufficient for this discussion. For example, compiling an example Solidity file, Example.sol, and sending the opcode output into a directory named BytecodeDir is accomplished with the following command:

$ solc -o BytecodeDir --opcodes Example.sol

You can also use --asm to produce a more human-readable output:

$ solc -o BytecodeDir --asm Example.sol

The following command will produce the bytecode binary for our example program:

$ solc -o BytecodeDir --bin Example.sol

The output opcode files generated will depend on the specific contracts contained within the Solidity source file. Our simple Solidity file Example.sol has only one contract, named Example:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

pragma solidity 0.8.27;

contract Example {

address contractOwner;

function test() public {

contractOwner = msg.sender;

}

}

As you can see, all this contract does is hold one persistent state variable, which is set as the address of the last account to run this contract.

If you look in the BytecodeDir directory, you will see the opcode file Example.opcode, which contains the EVM opcode instructions of the example contract. Opening the Example.opcode file in a text editor will show the following:

PUSH1 0x80 PUSH1 0x40 MSTORE CALLVALUE DUP1 ISZERO PUSH1 0xE JUMPI PUSH0 PUSH0 REVERT JUMPDEST POP PUSH1 0xA9 DUP1 PUSH1 0x1A PUSH0 CODECOPY PUSH0 RETURN INVALID PUSH1 0x80 PUSH1 0x40 MSTORE CALLVALUE DUP1 ISZERO PUSH1 0xE JUMPI PUSH0 PUSH0 REVERT JUMPDEST POP PUSH1 0x4 CALLDATASIZE LT PUSH1 0x26 JUMPI PUSH0 CALLDATALOAD PUSH1 0xE0 SHR DUP1 PUSH4 0xF8A8FD6D EQ PUSH1 0x2A JUMPI JUMPDEST PUSH0 PUSH0 REVERT JUMPDEST PUSH1 0x30 PUSH1 0x32 JUMP JUMPDEST STOP JUMPDEST CALLER PUSH0 PUSH0 PUSH2 0x100 EXP DUP2 SLOAD DUP2 PUSH20 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF MUL NOT AND SWAP1 DUP4 PUSH200xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF AND MUL OR SWAP1 SSTORE POP JUMP INVALID LOG2 PUSH5 0x6970667358 0x22 SLT KECCAK256 JUMPI 0xBB RETURNDATACOPY SWAP15 CALLVALUE 0xB3 0xB1 SMOD BLOBHASH STATICCALL MCOPY PUSH10 0x856E7132D8FEED4D83B6 0xB2 0xBE PUSH30 0x8B43532C818BFD64736F6C634300081B0033000000000000000000000000

Compiling the example with the --asm option produces a file named Example.evm in our BytecodeDir directory. This contains a slightly higher-level description of the EVM bytecode instructions, together with some helpful annotations:

/* "Example.sol":61:171 contract Example {... */

mstore(0x40, 0x80)

callvalue

dup1

iszero

tag_1

jumpi

revert(0x00, 0x00)

tag_1:

pop

dataSize(sub_0)

dup1

dataOffset(sub_0)

0x00

codecopy

0x00

return

stop

sub_0: assembly {

/* "Example.sol":61:171 contract Example {... */

mstore(0x40, 0x80)

callvalue

dup1

iszero

tag_1

jumpi

revert(0x00, 0x00)

tag_1:

pop

jumpi(tag_2, lt(calldatasize, 0x04))

shr(0xe0, calldataload(0x00))

dup1

0xf8a8fd6d

eq

tag_3

jumpi

tag_2:

revert(0x00, 0x00)

/* "Example.sol":109:169 function test() public {... */

tag_3:

tag_4

tag_5

jump // in

tag_4:

stop

tag_5:

/* "Example.sol":154:164 msg.sender */

caller

/* "Example.sol":138:151 contractOwner */

0x00

0x00

/* "Example.sol":138:164 contractOwner = msg.sender */

0x0100

exp

dup2

sload

dup2

0xffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff

mul

not

and

swap1

dup4

0xffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff

and

mul

or

swap1

sstore

pop

/* "Example.sol":109:169 function test() public {... */

jump // out

auxdata: 0xa264697066735822122057bb3e9e34b3b10749fa5e69856e7132d8feed4d83b6b2be7d8b43532c818bfd64736f6c634300081b0033

}

The --bin option produces the machine-readable hexadecimal bytecode:

6080604052348015600e575f5ffd5b5060a980601a5f395ff3fe6080604052348015600e575f5ffd5b50600436106026575f3560e01c8063f8a8fd6d14602a575b5f5ffd5b60306032565b005b335f5f6101000a81548173ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff021916908373ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff16021790555056fea264697066735822122057bb3e9e34b3b10749fa5e69856e7132d8feed4d83b6b2be7d8b43532c818bfd64736f6c634300081b0033

You can investigate what's going on here in detail using the opcode list given in "The EVM Instruction Set (Bytecode Operations)". However, that's quite a task, so let's start by just examining the first four instructions:

PUSH1 0x80 PUSH1 0x40 MSTORE CALLVALUE

Here, we have PUSH1 followed by a raw byte of value 0x80. This EVM instruction takes the single byte following the opcode in the program code (as a literal value) and pushes it onto the stack. It is possible to push values of size up to 32 bytes onto the stack, as in:

PUSH32 0x436f6e67726174756c6174696f6e732120536f6f6e20746f206d617374657221

The second PUSH1 opcode from example.opcode stores 0x40 onto the top of the stack (pushing the 0x80 already present there down one slot).

Next is MSTORE, which is a memory store operation that saves a value to the EVM's memory. It takes two arguments and, like most EVM operations, obtains them from the stack. For each argument, the stack is "popped"—that is, the top value on the stack is taken off, and all the other values on the stack are shifted up one position. The first argument for MSTORE is the address of the word in memory where the value to be saved will be put. For this program, we have 0x40 at the top of the stack, so that is removed from the stack and used as the memory address. The second argument is the value to be saved, which is 0x80 here. After the MSTORE operation is executed, our stack is empty again, but we have the value 0x80 (128 in decimal) at the memory location 0x40.

The next opcode is CALLVALUE, which is an environmental opcode that pushes onto the top of the stack the amount of ether (measured in wei) sent with the message call that initiated this execution.

We could continue to step through this program in this way until we had a full understanding of the low-level state changes that this code effects, but it wouldn't help us at this stage. We'll come back to it later in the chapter.

Contract Deployment Code

There is an important but subtle difference between the code used when creating and deploying a new contract on the Ethereum platform and the code of the contract itself. To create a new contract, a special transaction is needed that has an empty to field (null) and its data field set to the contract's initiation code. When such a contract-creation transaction is processed, the code for the new contract account is not the code in the data field of the transaction. Instead, an EVM is instantiated with the code in the data field of the transaction loaded into its program code ROM, and then the output of the execution of that deployment code is taken as the code for the new contract account. This is so that new contracts can be programmatically initialized using the Ethereum world state at the time of deployment, setting values in the contract's storage and even sending ether or creating further new contracts.

When compiling a contract offline—for example, using solc on the command line—you can get either the deployment bytecode or the runtime bytecode. The deployment bytecode is used for every aspect of the initialization of a new contract account, including the bytecode that will actually end up being executed when transactions call this new contract (i.e., the runtime bytecode) and the code to initialize everything based on the contract's constructor. The runtime bytecode, on the other hand, is exactly the bytecode that ends up being executed when the new contract is called and nothing more; it does not include the bytecode needed to initialize the contract during deployment.

Let's take the simple Faucet.sol contract we created in previous chapters as an example:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

pragma solidity 0.8.27;

contract Faucet {

// Give out ether to anyone who asks

function withdraw(uint256 _withdrawAmount, address payable _to) public {

// Limit withdrawal amount

require(_withdrawAmount <= 1000000000000);

// Send the amount to the address that requested it

_to.transfer(_withdrawAmount);

}

// Function to receive Ether. msg.data must be empty

receive() external payable {}

// Fallback function is called when msg.data is not empty

fallback() external payable {}

}

To get the deployment bytecode, we would run solc --bin Faucet.sol. If we instead wanted just the runtime bytecode, we would run solc --bin-runtime Faucet.sol. If you compare the output of these commands, you will see that the runtime bytecode is a subset of the deployment bytecode. In other words, the runtime bytecode is entirely contained within the deployment bytecode.

CREATE Versus CREATE2 to Deploy Contracts on Chain

CREATE and CREATE2 are the only two opcodes that let you deploy a new contract on chain. The main difference between them is related to the resulting address of the newly created contract. With CREATE the destination address is calculated as follows:

address = keccak256[rlp(sender_address ++ sender_nonce)][12:]

It's the rightmost 20 bytes of the Keccak-256 hash of the RLP encoding of the sender address followed by its nonce.

CREATE2 was added during the Constantinople hard fork in 2019 to let developers create new contracts where the resulting address isn't dependent on the state (i.e., the nonce) of the sender. In fact, it behaves in the exact same way as the CREATE opcode, but the destination address is calculated like this:

address = keccak256(0xff ++ sender_address ++ salt ++ keccak256(init_code))[12:]

where:

init_codeis the deployment bytecode of the new contract.saltis a 32-byte value (taken from the stack)

Disassembling the Bytecode

Disassembling EVM bytecode is a great way to understand how high-level Solidity acts in the EVM. There are a few disassemblers you can use to do this:

- Ethersplay is an EVM plug-in for Binary Ninja, a disassembler. By the way, to use plug-ins, you need to buy the complete app of Binary Ninja.

- Heimdall is an advanced EVM smart contract toolkit specializing in bytecode analysis and extracting information from unverified contracts.

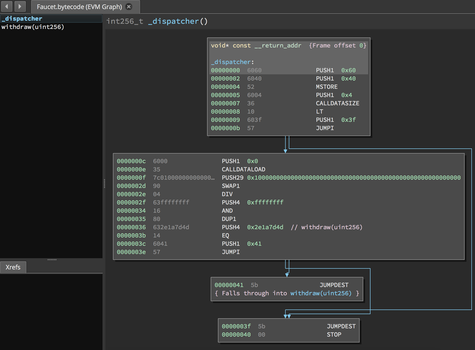

In this section, we will be using Heimdall to produce Figure 14-21. After getting the runtime bytecode of Faucet.sol, we can feed it to Heimdall to see what the EVM instructions look like.

Figure 14-21. Disassembling the Faucet runtime bytecode

Installing Heimdall

First, you need to ensure that Rust is installed on your computer. If it's not, run the following command:

$ curl https://sh.rustup.rs -sSf | sh

Then, run these two commands, one after the other:

$ curl -L http://get.heimdall.rs | bash

$ bifrost

Now, you should have Heimdall correctly installed. You can verify that by running:

$ heimdall --version

You should see something like this:

$ heimdall --version

heimdall 0.8.4

Note

For the latest information on how to install Heimdall, please refer to the official documentation you can find on the GitHub repository.

Disassembling the bytecode with Heimdall

Now that we have correctly installed Heimdall, we are ready to generate the same graph you saw in Figure 14-21. Starting with the runtime bytecode of our Faucet.sol contract, you can run the following command:

$ heimdall cfg <insert the runtime bytecode here>

Here is an example of what this command should look like:

$ heimdall cfg 608060405260043610610…

Now, you should see a new folder called output. Enter it and again enter the generated folder called local. Here, you should find the file cfg.dot:

$ cd output

$ cd local

$ ls # now you should see the file

Since it's a .dot file, we need a special program to open it correctly. In this example, we're going to use a website that lets us paste the contents of the .dot file and then generates the graph for us.

First, you need to copy the contents of the .dot file:

$ cat cfg.dot

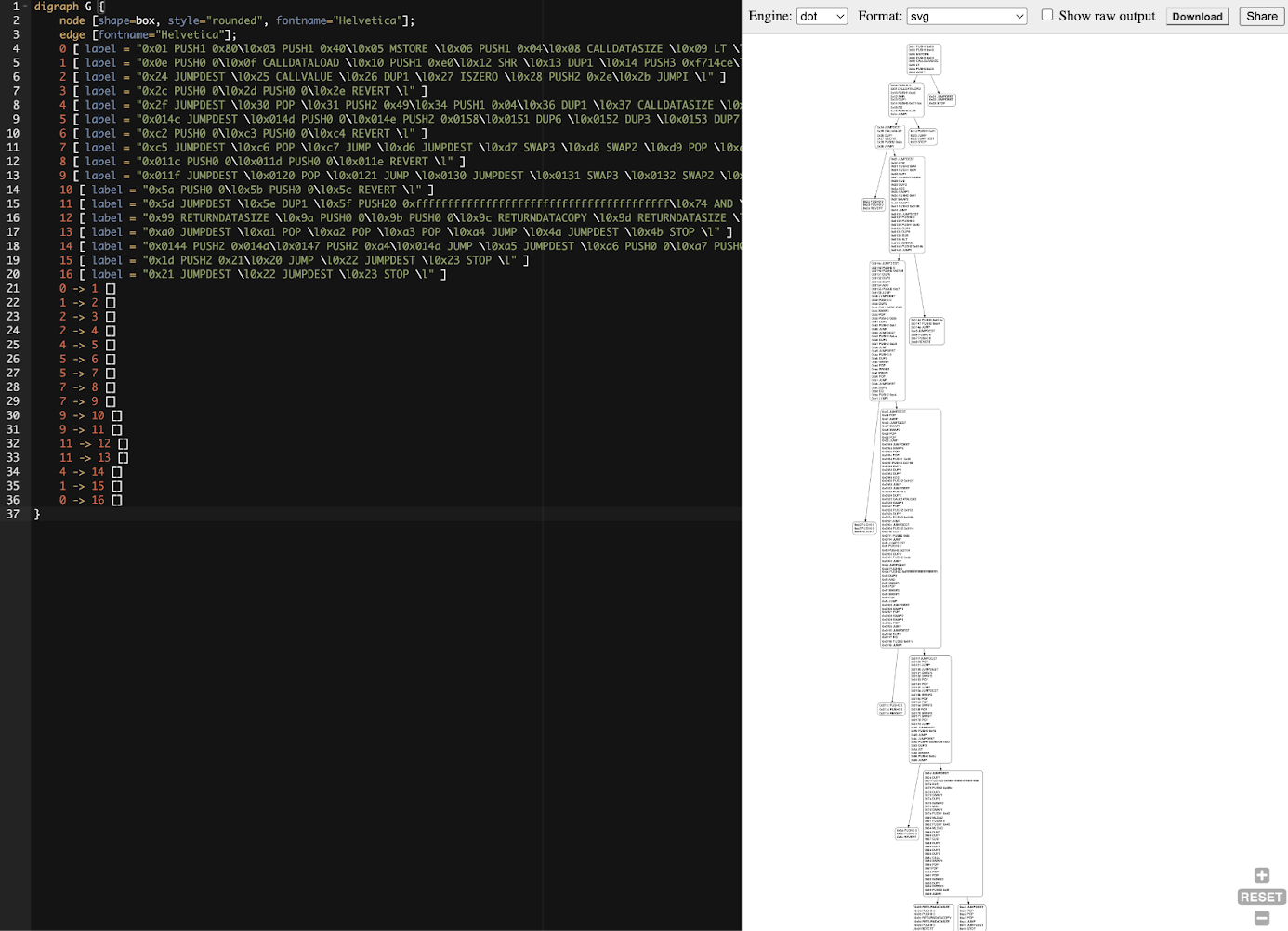

This command prints to screen the entire contents of the file; copy it, open a control flow graph (CFG) online generator, and paste it on the left side of the web page, as shown in Figure 14-22.

Figure 14-22. The control flow graph (CFG) of the Faucet.sol contract

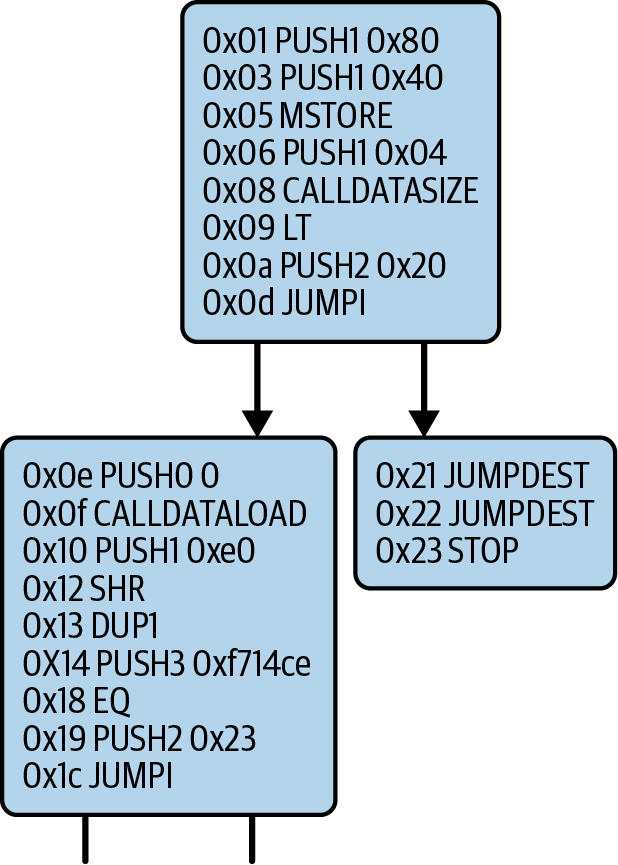

Figure 14-23 shows the initial bytecode of the Faucet.sol contract. As you can see, it starts with the same pattern as the previous Example.sol contract: PUSH1 0x80 PUSH1 0x40 MSTORE.

Figure 14-23. A zoom-in into the first part of the CFG graph

When you send a transaction to an ABI-compatible smart contract (which you can assume all contracts are), the transaction first interacts with that smart contract's dispatcher. The dispatcher reads in the data field of the transaction and sends the relevant part to the appropriate function. We can see an example of a dispatcher at the beginning of our disassembled Faucet.sol runtime bytecode. After the familiar MSTORE instruction, we see the following instructions:

PUSH1 0x04

CALLDATASIZE

LT

PUSH2 0x0020

JUMPI

As we have seen, PUSH1 0x04 places 0x04 onto the top of the stack, which is otherwise empty. CALLDATASIZE gets the size in bytes of the data sent with the transaction (known as the calldata) and pushes that number onto the stack. After these operations have been executed, the stack looks like this:

Stack

<length of calldata from tx>

0x4

This next instruction is LT, short for "less than." The LT instruction checks whether the top item on the stack is less than the next item on the stack. In our case, it checks to see if the result of CALLDATASIZE is less than 4 bytes.

Why does the EVM check to see that the calldata of the transaction is at least 4 bytes? Because of how function identifiers work. Each Solidity function is identified by the first 4 bytes of its Keccak-256 hash. By placing the function's name and all the arguments it takes into a keccak256 hash function, we can deduce its function identifier. In our case, we have:

keccak256("withdraw(uint256,address)") = 0x00f714ce...

Thus, the function identifier for the withdraw(uint256,address) function is 0x00f714ce, since these are the first 4 bytes of the resulting hash. A function identifier is always 4 bytes long, so if the entire data field of the transaction sent to the contract is less than 4 bytes, then there's no function with which the transaction could possibly be communicating, unless a fallback function is defined. Because we implemented such a fallback function in Faucet.sol, the EVM jumps to this function when the calldata's length is less than 4 bytes.

LT pops the top two values off the stack and, if the transaction's data field is less than 4 bytes, pushes 1 onto it. Otherwise, it pushes 0. In our example, let's assume the data field of the transaction sent to our contract was less than 4 bytes.

The PUSH2 0x0020 instruction pushes the bytes 0x0020 onto the stack. After this instruction, the stack looks like this:

Stack

0x0020

0x1

The next instruction is JUMPI, which stands for "jump if." It works like so:

jumpi(label, cond) // Jump to "label" if "cond" is true

In our case, label is 0x0020, which is where our fallback function lives in our smart contract. The cond argument is 1, which was the result of the LT instruction earlier. To put this entire sequence into words, the contract jumps to the fallback function if the transaction data is less than 4 bytes.

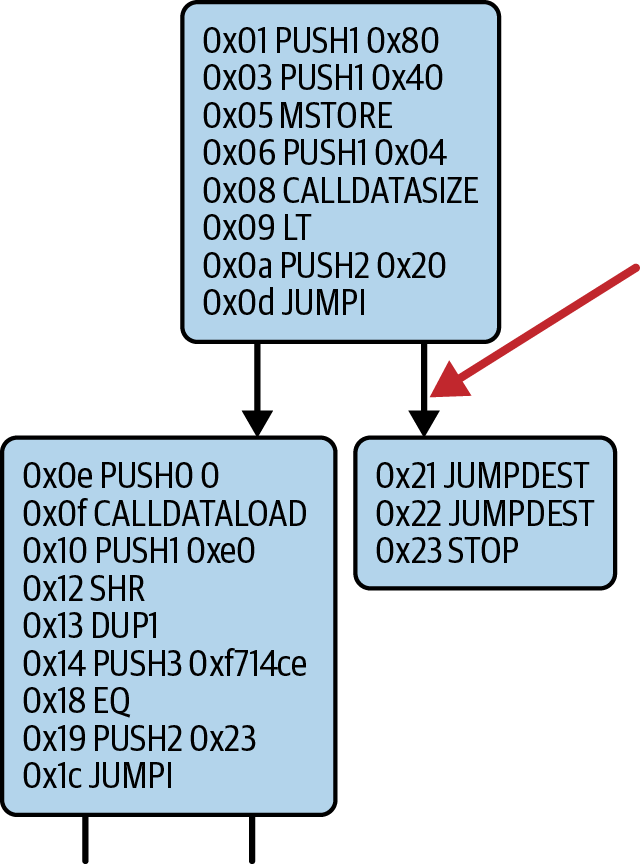

At 0x20, after two JUMPDEST instructions, only a STOP instruction follows because, although we declared a fallback function, we kept it empty. As you can see in Figure 14-24, had we not implemented a fallback function, the contract would throw an exception instead.

Figure 14-24. JUMPI instruction leading to fallback function

Note

Heimdall represents the bytecode starting with offset equal to 0x01, even though the EVM actually interprets it as starting with offset 0x00. In the previous example, the JUMPI instruction tells the EVM to go to offset 0x20 if the condition is true, but in the graph, offset 0x20 is here represented as 0x21. As a rule of thumb, you just need to add one to every offset of the EVM to find it on the graph.

Let's examine the central block of the dispatcher. Assuming we received calldata that was greater than 4 bytes in length, the JUMPI instruction would not jump to the fallback function. Instead, code execution would proceed to the following instructions:

PUSH0 0x0

CALLDATALOAD

PUSH1 0xe0

SHR

DUP1

PUSH3 0xf714ce

EQ

PUSH2 0X23

JUMPI

PUSH0 pushes 0 onto the stack, which is now otherwise empty again. CALLDATALOAD accepts as an argument an index within the calldata sent to the smart contract and reads 32 bytes from that index, like so:

calldataload(p) //load 32 bytes of calldata starting from byte position p

Since 0 was the index passed to it from the PUSH0 command, CALLDATALOAD reads 32 bytes of calldata starting at byte 0 and then pushes it to the top of the stack (after popping the original 0x0). After the PUSH1 0xe0 instruction, the stack is then:

Stack

0xe0

<32 bytes of calldata starting at byte 0>

SHR performs a logical right shift of 0xe0 bits (224 bits, 28 bytes) to the 32-byte value element on the stack. By shifting the calldata to the right by 28 bytes, it isolates the first 4 bytes of the calldata. In fact, when shifting to the right, all the bits move before the first one are discarded, while the new bits are set to 0. Remember that the first 4 bytes of the calldata represent the function identifier of the function we want to trigger.

Logical Bit Shift Example

You can better understand this with an example. Let's say the stack is:

Stack

0x1234567890 // a 5 bytes element

We want to get only the first two bytes (i.e., 0x1234). To achieve this using only EVM opcodes, we can do:

PUSH1 0x18 // this represents the number 24 in hex, 24 bits = 3 bytes

SHR

In fact, by shifting the stack of items 3 bytes to the right (remember that each byte is represented here as 2 hex digits), we obtain the following item:

0x0000001234 | 4567890

The 4567890 part is discarded, and all that remains is:

Stack

0x1234

All the leading zeros can be ignored as they are not significant.

The new stack is:

Stack

<function identifier sent in data>

The next instruction is DUP1, which duplicates the first item in the stack. The stack is now:

Stack

<function identifier sent in data>

<function identifier sent in data>

Now there is a PUSH3 instruction, followed by the push data 0xf714ce. This opcode simply pushes the (push) data onto the stack. After this opcode, the stack looks like this:

Stack

0xf714ce

<function identifier sent in data>

<function identifier sent in data>

Now, does the 0xf714ce look familiar to you? Do you remember what the function identifier of our withdraw(uint256,address) function is? It's 0x00f714ce… Note that they are the same number as leading zeros can be ignored.

The next instruction, EQ, pops off the top two items of the stack and compares them. This is where the dispatcher does its main job: it compares whether the function identifier sent in the msg.data field of the transaction matches that of withdraw(uint256,address). If they're equal, EQ pushes 1 onto the stack, which will ultimately be used to jump to the withdraw function. Otherwise, EQ pushes 0 onto the stack.

Assuming the transaction sent to our contract indeed began with the function identifier for withdraw(uint256,address), our stack has become:

Stack

1

<function identifier sent in data> (now known to be 0x00f714ce)

Next, we have PUSH2 0x23, which is the address at which the withdraw(uint256,address) function lives in the contract. After this instruction, the stack looks like this:

Stack

0x23

1

<function identifier sent in msg.data>

The JUMPI instruction is next, and it once again accepts the top two elements on the stack as arguments. In this case, we have JUMPI(0x23, 1), which tells the EVM to execute the jump to the location of the withdraw(uint256,address) function, and the execution of that function's code can proceed.

Turing Completeness and Gas

As we have already touched on, in simple terms a system or programming language is Turing complete if it can run any program. This capability, however, comes with a very important caveat: some programs take forever to run. An important aspect of this is that we can't tell just by looking at a program whether it will take forever or not to execute. We have to actually go through with the execution of the program and wait for it to finish to find out. Of course, if it is going to take forever to execute, we will have to wait forever to find out. This is called the halting problem and would be a huge problem for Ethereum if it were not addressed.

Because of the halting problem, the Ethereum world computer is at risk of being asked to execute a program that never stops. This could be by accident or malice. We have described how Ethereum acts like a single-threaded machine, without any scheduler, and so if it became stuck in an infinite loop, that would mean that Ethereum would become unusable.

With gas, there is a solution, though: if after a prespecified maximum amount of computation has been performed, the execution hasn't ended, the execution of the program is halted by the EVM. This makes the EVM a quasi-Turing-complete machine: it can run any program you feed into it but only if the program terminates within a particular amount of computation. That limit isn't fixed in Ethereum—you can pay to increase it up to a maximum (called the block gas limit), and everyone can agree to increase that maximum over time. Nevertheless, at any one time, there is a limit in place, and transactions that consume too much gas while executing are halted.

In the following sections, we will look at gas and examine how it works in detail.

What Is Gas?

Gas is Ethereum's unit for measuring the computational and storage resources required to perform actions on the Ethereum blockchain. In contrast to Bitcoin, whose transaction fees take into account only the size of a transaction in kilobytes, Ethereum must account for every computational step performed by transactions and smart contract code execution.

Each operation performed by a transaction or contract costs a fixed amount of gas. Some examples from the Ethereum "Yellow Paper" include:

- Adding two numbers costs 3 gas

- Calculating a Keccak-256 hash costs 30 gas + 6 gas for each 256 bits of data being hashed

- Sending a transaction costs 21,000 gas

Gas is a crucial component of Ethereum and serves a dual role: as a buffer between the (volatile) price of ether and the reward to validators for the work they do and as a defense against DoS attacks. To prevent accidental or malicious infinite loops or other computational wastage in the network, the initiator of each transaction is required to set a limit to the amount of computation they are willing to pay for. The gas system thereby disincentivizes attackers from sending "spam" transactions since they must pay proportionately for the computational, bandwidth, and storage resources that they consume.

Gas Accounting During Execution

When an EVM is needed to complete a transaction, in the first instance it is given a gas supply equal to the amount specified by the gas limit in the transaction. Every opcode that is executed has a cost in gas, and so the EVM's gas supply is reduced as the EVM steps through the program. Before each operation, the EVM checks that there is enough gas to pay for the operation's execution. If there isn't enough gas, execution is halted and the transaction is reverted.

If the EVM reaches the end of execution successfully without running out of gas, the gas cost used is paid to the validator as a transaction fee, converted to ether based on the gas price specified in the transaction:

validator fee = gas cost × gas price

The gas remaining in the gas supply is refunded to the sender, again converted to ether based on the gas price specified in the transaction:

remaining gas = gas limit – gas cost

refunded ether = remaining gas × gas price

If the transaction "runs out of gas" during execution, the operation is immediately terminated, raising an OOG exception. The transaction is reverted, and all changes to the state are rolled back. Although the transaction was unsuccessful, the sender will be charged a transaction fee because validators have already performed the computational work up to that point and must be compensated for doing so.

Gas accounting considerations

The relative gas costs of the various operations that can be performed by the EVM have been carefully chosen to best protect the Ethereum blockchain from attack. More computationally intensive operations cost more gas. For example, executing the SHA3 function is 10 times more expensive (30 gas) than the ADD operation (3 gas). More important, some operations, such as EXP, require an additional payment based on the size of the operand. There is also a gas cost to using EVM memory and for storing data in a contract's on-chain storage.

The importance of matching gas cost to the real-world cost of resources was demonstrated in 2016 when an attacker found and exploited a mismatch in costs. The attack generated transactions that were very computationally expensive and made the Ethereum mainnet almost grind to a halt. This mismatch was resolved by a hard fork (codenamed "Tangerine Whistle") that tweaked the relative gas costs.

Gas accounting in the future of Ethereum

Gas metering was and remains an extremely important part of how Ethereum handles the entire load of transactions in the network. It's very important to understand that gas costs are a key incentive for certain kinds of behaviors. In the future, there may be some changes in how much gas different opcodes consume.

For example, before the Cancun upgrade that introduced EIP-4844 blob transactions, all L2s were posting their data on Ethereum as part of the calldata of a transaction. That data is forever stored on all of Ethereum's nodes. Now that L2s have a better way to post their data on Ethereum through blob transactions, it's possible that in the future, calldata will become even more expensive than it is now to encourage rollups to use blob transactions and to lessen the burden for nodes of storing all that data forever.

Gas cost versus gas price

While the gas cost is a measure of computation and storage used by a transaction in the EVM, the gas itself also has a price measured in ether. When performing a transaction, the sender specifies the gas price they are willing to pay (in ether) for each unit of gas, allowing the market to decide the relationship between the price of ether and the cost of computing operations (as measured in gas):

transaction fee = total gas used × gas price paid (in ether)

When constructing a new block, validators on the Ethereum network can choose among pending transactions by selecting those that offer to pay a higher gas price. Offering a higher gas price will therefore incentivize validators to include your transaction and get it confirmed faster.

In practice, the sender of a transaction will set a gas limit that is higher than or equal to the amount of gas expected to be used. If the gas limit is set higher than the amount of gas consumed, the sender will receive a refund of the excess amount since validators are compensated only for the work they actually perform.

It is important to be clear about the distinction between the gas cost and the gas price. To recap:

- Gas cost is the number of units of gas required to perform a particular operation.

- Gas price is the amount of ether you are willing to pay per unit of gas when you send your transaction to the Ethereum network.

Tip

Although gas has a price, it cannot be "owned" or "spent." Gas exists only inside the EVM, as a count of how much computational work is being performed. The sender is charged a transaction fee in ether, which is converted to gas for EVM accounting and then back to ether as a transaction fee paid to the validators.

Negative gas costs

Ethereum encourages the deletion of used storage variables by refunding some of the gas used during contract execution. There is only operation in the EVM with negative gas costs: changing a storage address from a nonzero value to zero (SSTORE[x] = 0) is worth a refund. The amount of refunded gas isn't fixed and depends on the values of the storage slot before and after this operation. To avoid exploitation of the refund mechanism, the maximum refund for a transaction is set to one fifth of the total amount of gas cost (rounded down).

In the past, there was another operation with a negative gas cost: SELFDESTRUCT. Deleting a contract (through SELFDESTRUCT) was worth a refund of 24,000 gas. Right now, the SELFDESTRUCT opcode is deprecated, and not using it anymore is recommended.

Tip

Gas refunds are applied at the end of the transaction. So if a transaction doesn't have sufficient gas to reach the end of the execution, it fails, and no refunds are given.

Block Gas Limit

The block gas limit is the maximum amount of gas that may be consumed by all the transactions in a block. It constrains how many transactions can fit into a block.

For example, let's say we have five transactions whose gas limits have been set to 30,000, 30,000, 40,000, 50,000, and 50,000. If the block gas limit is 180,000, then any four of those transactions can fit in a block, while the fifth will have to wait for a future block. As previously discussed, validators decide which transactions to include into a block. Different validators are likely to select different combinations, mainly because they receive transactions from the network in a different order.

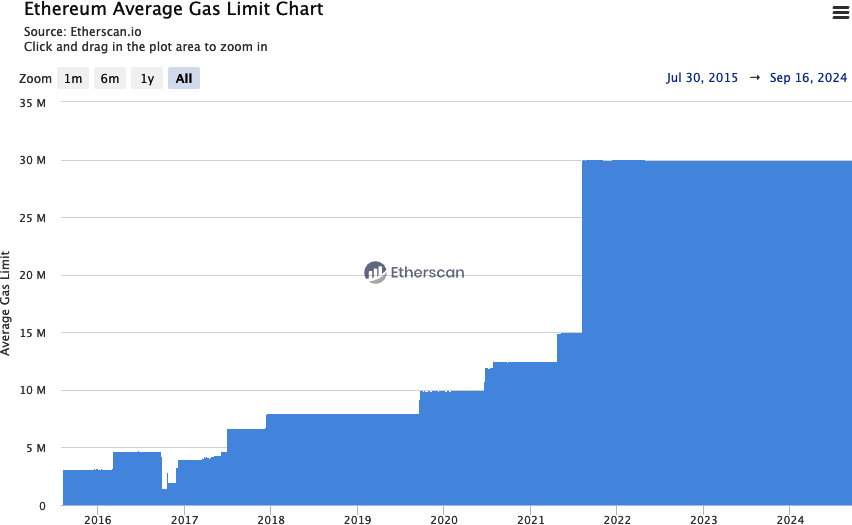

If a validator tries to include a transaction that requires more gas than the current block gas limit, the block will be rejected by the network. Most Ethereum clients will stop you from issuing such a transaction by giving a warning along the lines of "transaction exceeds block gas limit." According to Etherscan, the block gas limit on the Ethereum mainnet is 36 million gas at the time of writing (June 2025), meaning that around 1,428 basic—that is, ETH transfer—transactions (each consuming 21,000 gas) could fit into a block.

Who chooses the block gas limit?

Before the introduction of EIP-1559 on August 5, 2021, miners (Ethereum was using a PoW-based consensus algorithm at that time) had a built-in mechanism where they could vote on the block gas limit, so capacity could be increased or decreased in subsequent blocks. The miner of a block could vote to adjust the block gas limit by a factor of 1/1024 (0.0976%) in either direction. The result of this was an adjustable block size based on the needs of the network, following miners' hashpower.

Now, validators vote on the gas target—that is, how much gas a block should consume on average—and the gas limit is defined to be twice the target. The 1/1024 adjusting factor that each validator must comply with is maintained the same as before.

Why doesn't the block gas limit rise?

You may be wondering, if validators can vote on the gas target, which directly translates to the gas limit, why doesn't the block gas limit rise to one billion instead of being almost fixed at 30 million? A bigger block gas limit would mean that more transactions could fit into a block, so transactions would become cheaper for end users.

The answer is that raising the gas limit has some cons related to the decentralization of the network. In fact, while bigger blocks can include more transactions, that also means that blocks become harder to verify on time, and that could lead to the death of Ethereum nodes made with common hardware, leaving only powerful servers to validate full blocks. Not only that, but bigger blocks also mean a bigger state growth. The final outcome is the same as before: big servers would be the only ones able to fully run a node.

Historically, the block gas limit has been raised all at once during upgrades of the protocol, as you can see in Figure 14-25. And its value is generally set to a level suggested by core developers where we are sure all clients are able to handle the load of transactions and process blocks on time.

Figure 14-25. Ethereum average gas limit chart

Why Not Raise the Block Gas Limit?

Even though the block gas limit looks like it has been "fixed" at 30 million for more than three years, with PBS (see "Ethereum Stateless"), where actors with sophisticated hardware build the blocks—builders—and send them to proposers—validators—to publish them on the P2P network, there is an incentive to raise the block gas limit indefinitely while maintaining the actual gas used almost as a constant.

In fact, following EIP-1559, if the block gas target is much higher than the actual gas used, the base fee keeps decreasing, to the point where almost all of the gas fee goes to the validators instead of being burned (the base fee is burned, removing those ETH from the supply).

So the advantages for validators are twofold:

- They can keep the gas fees for themselves, instead of burning them and reducing the ETH supply.

- When necessary, they can create larger blocks that capture a lot of MEV activity, resulting in even more fees for them.

If you are curious about this, read more in James Prestwich's article.

Concrete Implementations

Every Ethereum node has a concrete implementation of the EVM described in this chapter. Here is a list of the most famous and used ones:

Go-ethereum EVM

Geth is the most adopted and oldest execution client. It contains a full implementation of the EVM written in Go.

Execution-spec EVM

The Ethereum Foundation maintains a Python repository on GitHub containing the specification related to the Ethereum execution client. It has a full EVM implementation written in Python.

Revm

Revm is one of the most used EVM implementations outside of normal Ethereum clients, thanks to its great customizability and adaptability.

Evmone

Evmone is probably the fastest EVM implementation. It is written in C++ and maintained by the Ipsilon team at the Ethereum Foundation.

Besu EVM

Besu is an execution client maintained by Consensys. It has a full implementation of the EVM written in Java.

Nethermind EVM

Nethermind EVM is an execution client written in C# that maintains a full implementation of the EVM.

The Biggest EVM Upgrade: EVM Object Format

EVM Object Format (EOF) is the biggest upgrade to the EVM since its birth in 2015. In fact, even though there have been modifications to the EVM in the past, which were mainly focused on the gas-metering aspect or on the introduction of new opcodes, the EVM is almost identical to how it was first created by Gavin Wood.

The EVM is still great. All activities happening today on Ethereum (and all other EVM-compatible blockchains) are only possible thanks to it. It's not perfect either, and during recent years, smart contract developers have had to deal with different aspects of it and learn some tricks to overcome its constraints.

EOF is an extensible and versioned container format for the EVM with a once-off validation at deploy time. In this section, we'll explore all the major limitations of the EVM and how EOF intends to overcome them.

Note

As of the final revision of this book (June 2025), the EOF upgrade has been postponed indefinitely due to insufficient consensus within the Ethereum community. There is currently no clear timeline for its implementation, and it may ultimately never be adopted. Nevertheless, we believe this section remains valuable for understanding how EOF could affect the EVM and the broader Ethereum ecosystem.

Jumpdest Analysis

Legacy EVM doesn't validate the bytecode published on chain at creation time. On the one hand, this may look good because it lets you post whatever contract you want: you can deploy bytecode containing non-existent opcodes or add code that is never touched or truncated in the middle of a PUSH operation without giving the next immediate value that it must have in order to execute correctly. This actually adds lots of inefficiencies. In fact, the EVM has to check everything at runtime, which adds complexity and slows the overall performance. Here is an example of a non-existent opcode included inside an EVM bytecode:

600C600052602060000C

Here is the bytecode translated into human-readable opcodes:

[00] PUSH1 0C

[02] PUSH1 00

[04] MSTORE

[05] PUSH1 20

[07] PUSH1 00

[09] NOT-EXISTING

Opcode 0C doesn't exist, and when the EVM gets to that point, it will panic and early return. Notice how the second byte in the previous bytecode is also 0C, but the EVM doesn't fail there. The difference is that while the last 0C byte is interpreted as an opcode and fails because it's not valid, the other one is interpreted as push data since it's the immediate value of the first PUSH1 opcode.

One key part of this runtime check is the jumpdest analysis. Every client needs to do it at runtime every time a contract is executed. Let's spend some time understanding this jumpdest analysis and why it is needed in legacy EVM.

Tip

To not have to perform jumpdest analysis at runtime every time a contract is called, some Ethereum node implementations save a jumpdest map for every contract. This map is created at contract deployment and saved inside the node's database.

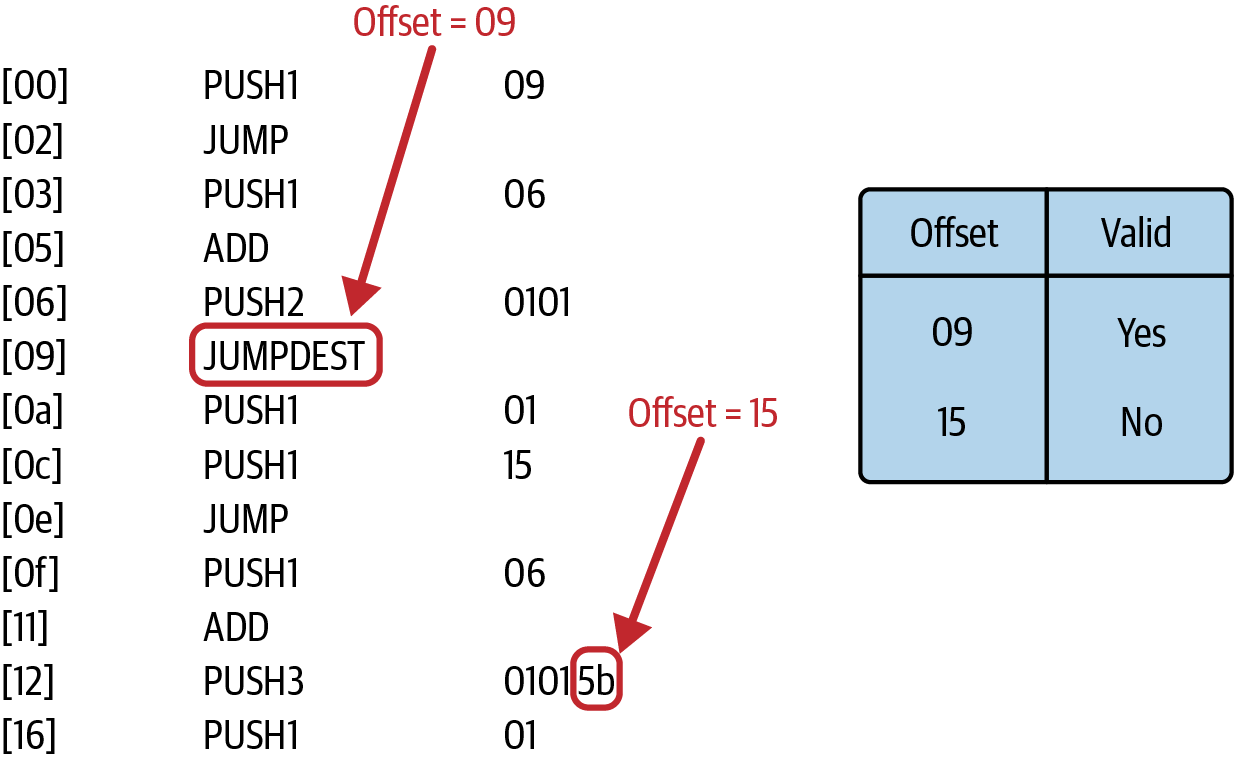

Legacy EVM has dynamic jumps (JUMP and JUMPI opcodes) only to manage the control flow of the bytecode. This is very handy because you can change the normal flow of operations with just two opcodes. The cons are that dynamic jumps are very expensive and require a deep validation at runtime, even though most of the time, there is no need for the jump to be dynamic. In fact, very often the value to jump to is pushed to the stack immediately before the JUMP opcode itself. Here is a small example:

…6009566006016101015b6001…

And translated into human-readable opcodes:

[00] PUSH1 09

[02] JUMP

[03] PUSH1 06

[05] ADD

[06] PUSH2 0101

[09] JUMPDEST

[0a] PUSH1 01

As you can see, the jump destination—that is, the offset 0x09 to jump to—is just pushed onto the stack through a PUSH1 opcode immediately before the JUMP opcode. The EVM pushes 0x09 onto the stack, then executes the JUMP opcode that takes as input the previously pushed 0x09 and moves the execution to the instruction at that offset. At 0x09, a JUMPDEST opcode is found, so it's considered a valid jump destination, and the execution can go on correctly.

Runtime validation is required in order to not jump to invalid destinations. Valid destinations are only JUMPDEST instructions that are not part of push data. This is very important to understand: legacy EVM doesn't have a proper separation between code and data. So whenever you meet the byte 0x5b—the JUMPDEST opcode—in some bytecode, you cannot be completely sure if that's a real JUMPDEST opcode or it's part of push data without analyzing the contract as a whole.

Take a look at the following example showing this subtle difference:

…6009566006016101015b6001…

…6009566006016201015b6001…

These two bytecodes look almost identical; in fact, they differ only by one bit. But that's enough to make a huge difference in the outcome. The first bytecode is the same as the one shown in the previous example. The second looks like this in human-readable format:

[00] PUSH1 09

[02] JUMP

[03] PUSH1 06

[05] ADD

[06] PUSH3 01015b

[0a] PUSH1 01

If you try to execute this second code, it will fail due to an invalid jump destination. It may look a bit weird because at offset 0x09, there's still the 0x5b byte, which represents the JUMPDEST opcode. The problem here relies on the fact that, in this case, the 0x5b byte is part of the push data, so it could not be considered a valid jump destination. This is why the execution fails at that point.

Jumpdest analysis is the process of analyzing a contract in order to know which jump destinations are valid and which are not so that when the EVM is executing the contract, it is able to detect an invalid jump destination and panic.

Let's say you're sending a transaction that interacts with Contract A. When the EVM loads it, it immediately performs jumpdest analysis to save the map of valid jump destinations and then starts with the real execution of the transaction:

…6009566006016101015b60016015566006016201015b6001…

Here it is in human-readable format:

[00] PUSH1 09

[02] JUMP

[03] PUSH1 06

[05] ADD

[06] PUSH2 0101

[09] JUMPDEST

[0a] PUSH1 01

[0c] PUSH1 15

[0e] JUMP

[0f] PUSH1 06

[11] ADD

[12] PUSH3 01015b

[16] PUSH1 01

The EVM skims through all the bytecode and creates a map where each 0x5b byte is marked as a valid or invalid jump destination, as you can see in Figure 14-26.

Figure 14-26. The client creates a jumpdest map to separate valid from invalid jump destinations

Adding and Deprecating Features

Adding or deprecating an opcode or a specific feature is not as easy as it may seem. While it is true that different opcodes have been added, such as BLOBHASH, BLOBBASEFEE, BASEFEE, and so on, this is always complicated because of the unstructured and not validated EVM's bytecode.

Have a look at the following example, which contains an invalid opcode, specifically 0x0C. Suppose this is a real contract deployed on Ethereum mainnet:

600C600052602060000C

Here it is in human-readable format:

[00] PUSH1 0C

[02] PUSH1 00

[04] MSTORE

[05] PUSH1 20

[07] PUSH1 00

[09] NOT-EXISTING

If you try to execute this small bytecode inside an EVM, you will see that when the execution gets to the not-existing opcode, it fails.

Let's say a future upgrade adds a new opcode, the MAX opcode, that takes two items from the stack and returns the one containing the bigger value. The byte assigned to it is 0x0C. Consider again the previous bytecode (remember, we're assuming it's a real contract deployed on mainnet):

[00] PUSH1 0C

[02] PUSH1 00

[04] MSTORE

[05] PUSH1 20

[07] PUSH1 00

[09] MAX

Now this bytecode has a completely different outcome. In fact, it doesn't fail anymore and returns successfully. This could create problems if there were contracts relying on the assumption that this contract always failed due to a (previously) not-existing opcode.

Deprecating a feature is even harder since you cannot rely on a versioning system of the EVM. So if you remove an opcode or change how it works, old contracts that were using it could break, and there is nothing apart from manual intervention (by creating a new contract) that can fix it.

When EIP-2929 was introduced to change the gas metering of state-access opcodes, some contracts broke because they were hard-coding the amount of gas to use or to expect. The solution to make them work again was to introduce access lists, where you can preload some accounts and storage slots that you know will be touched by the transaction and lower gas costs.

Other important aspects of legacy EVM that make upgrades harder are code introspection and gas observability. Gas observability is possible thanks to opcodes such as GAS or even all the *CALL opcodes that take gas as input, while code introspection is achievable because of opcodes such as CODESIZE, CODECOPY, EXTCODESIZE, EXTCODECOPY, and EXTCODEHASH.

The problem lies in the fact that if the EVM is able to access the remaining gas at a certain point of the execution, the logic of a smart contract can be made dependent on that. And if in the future, there is a change regarding gas metering of some opcodes (which is something not so rare to observe), there could be problems for all smart contracts that were relying on the old gas metering. The same applies for code introspection.

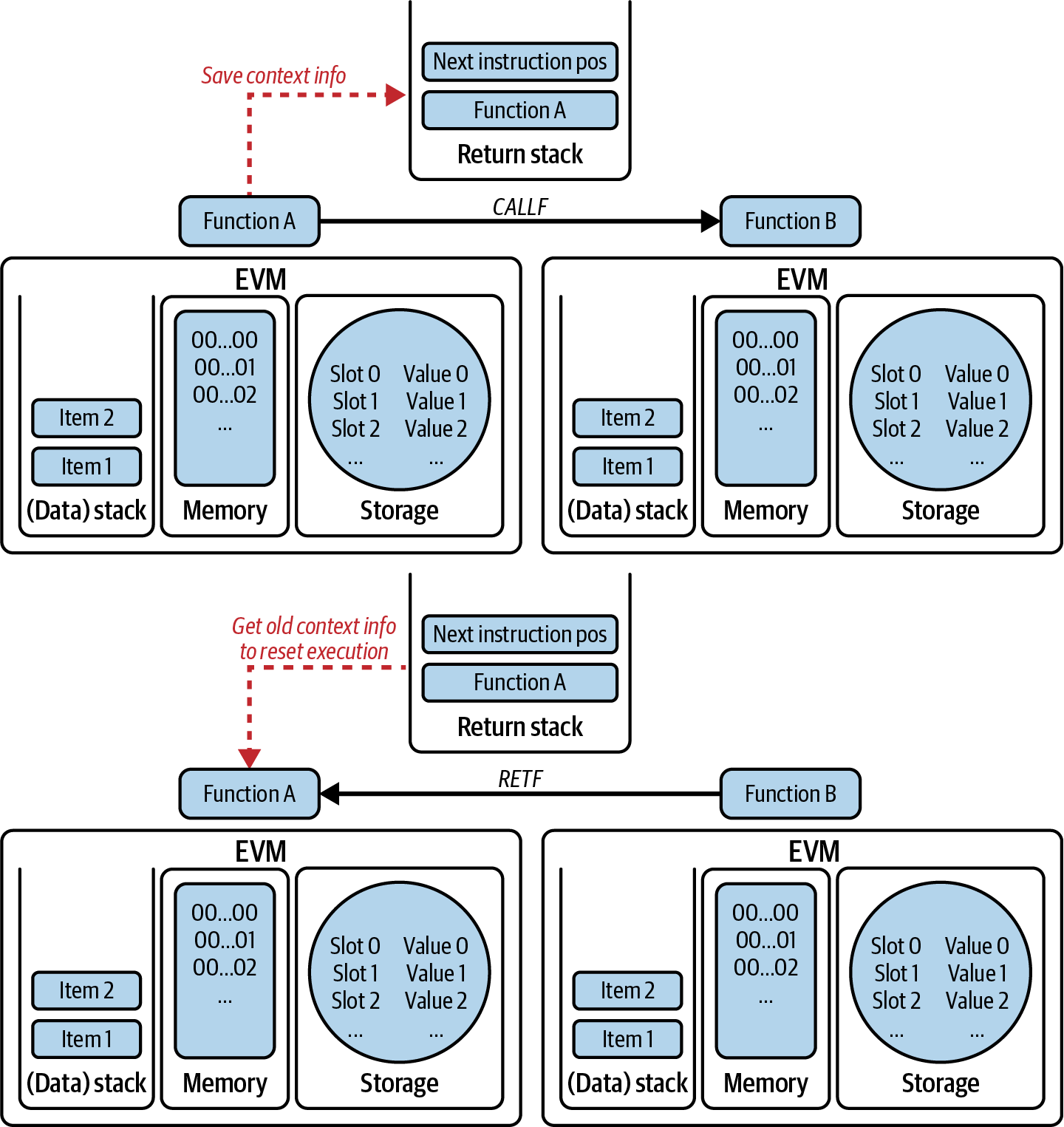

Note