Mastering Ethereum: 2nd Edition

This is the second edition of the book "Mastering Ethereum". You can access the book in the following ways:

Authors

License

This work is licensed under Creative Commons. For the first 12 months after publication, it is available under the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license (Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives). After that period, it becomes available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license (Attribution-ShareAlike).

Preface

This book is a collaboration between me (Carlo Parisi, aka Blackie), Alessandro Mazza, and Niccolò Pozzolini. The first edition, which of course heavily influenced our work, was written between 2016 and 2019 by Andreas M. Antonopoulos and Dr. Gavin Wood.

In November 2023, a series of very fortunate coincidences brought Andreas and me together in Glasgow. There, after a few beers and a few autographs, I asked him if he had any intention of writing a second edition of Mastering Ethereum. This was because, even though the first edition is a masterpiece, it hasn't aged well; it was published in 2019, back when Ethereum was still using proof of work and had a very different roadmap.

Andreas's response was that he wasn't planning to write a second edition, but our conversation ended up sparking the idea that led me to take on this project. Less than a day after our meeting in Glasgow, I was talking with O'Reilly about the possibility of writing a second edition.

I immediately knew this would be a big and important task. While I was honored by the opportunity, I was also afraid I might not be able to do a good enough job. I've been a fan of Andreas's work for years; he's the reason I was able to understand Bitcoin as deeply as I did back in 2014–2015, so I knew I needed help.

The first person who came to mind was Alessandro. He was involved in the project within the first few hours. As soon as the opportunity became real, I texted and asked if he wanted to join me. He instantly and happily said yes (without knowing any of the conditions or even whether it was a paid job).

Niccolò was a bit harder to convince. It took a full month of rejections to get him on board. Luckily, I'm very stubborn and wasn't willing to take no for an answer. After one month, he finally agreed. With that, our full team was ready, and the Mastering Ethereum: Second Edition project was officially launched.

I hope that every reader of this book gains at least a bit of knowledge from it. Mastering Ethereum was a book that taught me—and thousands of others—so much, and we worked hard to maintain that same level of quality. It took two years of research and writing to complete, and I'd be lying if I said it was easy.

We're also very proud to be an all-Italian team on this project. Hopefully, that brings some pride to the Italian crypto community as well.

How to Use This Book

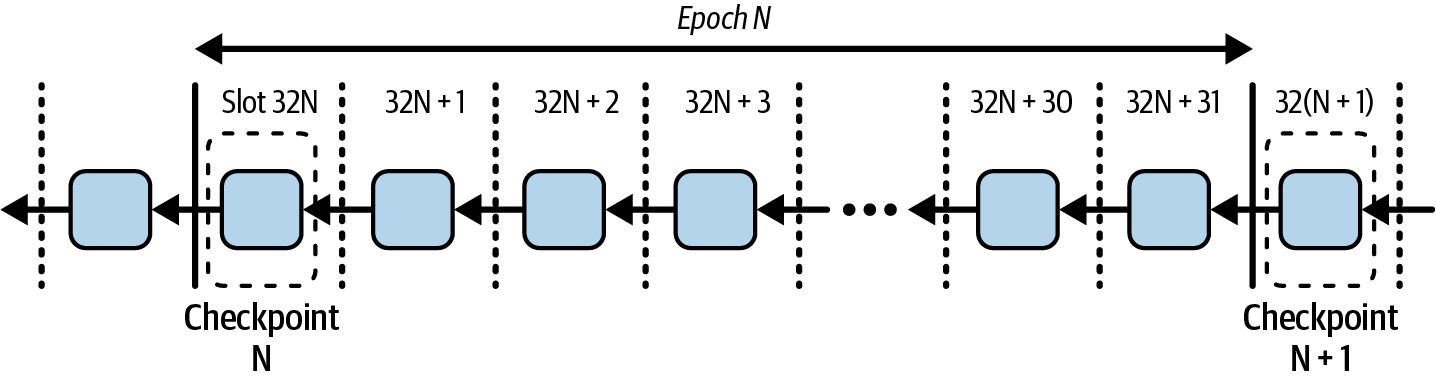

The book is intended to serve both as a reference manual and as a cover-to-cover exploration of Ethereum. The first two chapters offer a gentle introduction, suitable for novice users, and the examples in those chapters can be completed by anyone with a bit of technical skill. Those two chapters will give you a good grasp of the basics and allow you to use the fundamental tools of Ethereum. Parts of Chapter 3 and beyond are intended for programmers and include many technical topics and programming examples, but they still should be understandable by anyone, for the most part.

To serve as both a reference manual and a cover-to-cover narrative about Ethereum, the book inevitably contains some duplication. Some topics, such as gas, have to be introduced early enough for the rest of the topics to make sense but are also examined in depth in their own sections.

Finally, the book's index allows readers to find very specific topics and the relevant sections with ease, by keyword.

Intended Audience

This book is mostly intended for everyone. This book will teach you how smart contract blockchains work, how to use them, and how to develop smart contracts and decentralized applications with them. The first few chapters are also suitable as an in-depth introduction to Ethereum for beginners.

Code Examples

The examples are illustrated in Solidity, Vyper, and JavaScript, using the command line of a Unix-like operating system. All the code snippets can be replicated on most operating systems with a minimal installation of compilers, interpreters, and libraries for the corresponding languages. Where necessary, we provide basic installation instructions and step-by-step examples of the output of those instructions.

All the code snippets use real values and calculations where possible, so you can build from example to example and see the same results in any code you write to calculate the same values. For example, the private keys and corresponding public keys and addresses are all real. The sample transactions, contracts, blocks, and blockchain references have all been introduced to the actual Ethereum blockchain and are part of the public ledger, so you can review them.

Ethereum Addresses and Transactions in this Book

The Ethereum addresses, transactions, keys, QR codes, and blockchain data used in this book are, for the most part, real. That means you can browse the blockchain, look at the transactions offered as examples, retrieve them with your own scripts or programs, and so forth.

However, note that the private keys used to construct the addresses printed in this book have been "burned." This means that if you send money to any of these addresses, the money will be either lost forever or (more likely) appropriated, since anyone who reads the book can take it using the private keys printed herein.

Warning

Do not send money to any of the addresses in this book. Your money will be taken by another reader or lost forever.

Conventions Used in This Book

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

Italic

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant width

Used for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width bold

Shows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italic

Shows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

Tip

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

Note

This element signifies a general note.

Warning

This element indicates a warning or caution.

Using Code Examples

In our commitment to collaboration, we worked with O'Reilly Media to make this book available under a Creative Commons license.

If you have a technical question or a problem using the code examples, please send an email to support@oreilly.com.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you're reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing examples from O'Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product's documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but generally do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: "Mastering Ethereum, 2nd ed., by Andreas M. Antonopoulos, Gavin Wood, Carlo Parisi, Alessandro Mazza, and Niccolò Pozzolini (O'Reilly). Copyright 2026 Carlo Parisi, Alessandro Mazza, and Niccolò Pozzolini, 978-1-098-16842-1."

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

O'Reilly Online Learning

Note

For more than 40 years, O'Reilly Media has provided technology and business training, knowledge, and insight to help companies succeed.

Our unique network of experts and innovators share their knowledge and expertise through books, articles, and our online learning platform. O'Reilly's online learning platform gives you on-demand access to live training courses, in-depth learning paths, interactive coding environments, and a vast collection of text and video from O'Reilly and 200+ other publishers. For more information, visit oreilly.com.

How to Contact Us

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

O'Reilly Media, Inc.

141 Stony Circle, Suite 195

Santa Rosa, CA 95401

800-889-8969 (in the United States or Canada)

707-827-7019 (international or local)

707-829-0104 (fax)

oreilly.com/about/contact.html

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata and any additional information. You can access this page at https://oreil.ly/MasteringEthereum2e.

For news and information about our books and courses, visit https://oreilly.com.

Find us on LinkedIn

Watch us on YouTube

Contacting Carlo

Subscribe to Carlo's channel on YouTube

Follow Carlo on Twitter/X

Connect with Carlo on LinkedIn

Email: carlo.parisi01234@gmail.com

Contacting Alessandro

Follow Alessandro on GitHub

Connect with Alessandro on LinkedIn

Follow Alessandro on Twitter/X (Italian profile)

Follow Alessandro on Twitter/X (English profile)

Subscribe to Alessandro's YouTube channel

Contacting Niccolò

Follow Niccolò on Twitter/X

Connect with Niccolò on LinkedIn

Acknowledgments by Carlo

I owe a lot of what has happened in my career and personal life to Andreas's work. Thanks to the first edition of Mastering Bitcoin, I was able, back in 2014 and 2015, to truly understand the potential of Bitcoin. Because of that, I decided to pursue a career in crypto. At the time, there weren't many complete resources available, so Mastering Bitcoin was an incredible gift to the entire community. I wouldn't have the career I have today and probably my life would be very different if it weren't for that incredible work. The same goes for Mastering Ethereum. For this reason, Andreas, thank you so much.

Thank you to Nicola Luigi Guglielmo Di Nanna, my high school computer science professor. Without you, I probably would not have discovered my passion for programming and, subsequently, for blockchains. They say a good professor can change a student's life; you certainly did. Thank you for sharing your passion for computer science and for being such an inspiring role model.

Thank you also to Alessandro and Niccolò, who helped so much in writing this book, and to all of our incredible tech reviewers.

Thank you to Michelle Smith and Shira Evans from O'Reilly, who supported us every step of the way.

Thank you to the Italian community, particularly my own community on Discord, YouTube, and Twitter, which gave me the confidence to take on this and many other projects.

Thank you to the amazing Ethereum community. We wouldn't have been able to do as much research—or write as deeply—without your ongoing support and contributions.

And last but not least, thank you to my wonderful family, who supported me in everything I did and allowed me to freely explore my passions and interests.

Acknowledgments by Alessandro

There are so many things I'm grateful for. First of all, I'd like to thank Carlo for reaching out to me and giving me the amazing opportunity to write this book. I still remember the first time we met in person, in Catanzaro, Italy.

Thank you to my university professor, Dr. Luca Giuzzi, for allowing me to dedicate my thesis to Bitcoin and the Schnorr digital signature algorithm. That was the beginning of my career in the cryptocurrency space.

A heartfelt thank you to my Italian community, who gave me confidence and indirectly brought me to where I am today. I probably wouldn't have met Carlo if it weren't for their support.

Thank you to O'Reilly, and in particular to Shira Evans and Michelle Smith, who guided us throughout this journey. Their meticulous coordination and support, along with the help of all the reviewers, made this book possible.

Finally, I want to thank my family and my girlfriend, Alessandra, for always supporting and loving me.

Acknowledgments by Niccolò

I want to thank Carlo for giving me the chance to write this book with him. Over the past two years, we've worked on many projects together and shared plenty of laughs, trips abroad, and now this book. Working with you has made this journey both fun and rewarding.

I'm grateful to Andreas and Gavin for creating the first version of Mastering Ethereum. Their book opened my eyes to the world of blockchain and has done the same for so many others. Their work helped build and grow this amazing blockchain community that we're all part of today.

A big thank you to Michelle Smith and Shira Evans from O'Reilly for supporting us from start to finish. You helped us with all the paperwork, kept us on schedule, and guided us through the whole process of making this book a reality.

To my family, my friends, and my girlfriend, Giuditta, I can't thank you enough for always being there for me. During the many months of writing, you put up with my busy schedule and stress. You listened when I needed to talk through ideas, you understood when I couldn't make it to gatherings because of deadlines, and you kept encouraging me when things got tough. Your constant support gave me the strength and focus to keep going. The book you're holding isn't just my work; it exists because of the love and support you've always shown me.

Contributions

We'd all like to thank our tech reviewers:

- Ben Edgington

- Caleb Lent

- Brian Wu

- Gonçalo Magalhães

They have helped us immensely in improving the quality of the book. Thank you so much to our wonderful tech reviewers.

Chapter 1. What Is Ethereum?

Ethereum is often described as the “world computer.” But what does that mean? Let’s start with a computer science–focused description and then try to decipher that with a more practical analysis of Ethereum’s capabilities and characteristics while comparing it to Bitcoin and other decentralized information exchange platforms (or blockchains, to be precise).

From a computer science perspective, Ethereum is a deterministic but practically unbounded state machine, consisting of a globally accessible singleton state and a virtual machine that applies changes to that state.

From a more practical perspective, Ethereum is an open source, globally decentralized computing infrastructure that executes programs called smart contracts. It uses a blockchain to synchronize and store the system’s state changes, along with a cryptocurrency called ether to meter and constrain execution resource costs.

The Ethereum platform enables developers to build powerful decentralized applications with built-in economic functions. It provides high availability, auditability, transparency, and neutrality while reducing or eliminating censorship and reducing certain counterparty risks.

Ethereum Compared to Bitcoin

Many people approach Ethereum with some prior experience of cryptocurrencies, specifically Bitcoin. Ethereum shares many elements with other open blockchains: a peer-to-peer (P2P) network connecting participants; a Byzantine, fault-tolerant consensus algorithm for synchronization of state updates; the use of cryptographic primitives, such as digital signatures and hashes; and a digital currency (ether). Yet in many ways, both the purpose and construction of Ethereum are strikingly different from those of the open blockchains that preceded it, including Bitcoin.

Ethereum’s purpose is not primarily to be a digital currency payment network. While the digital currency ether is both integral to and necessary for the operation of Ethereum, ether is intended as a utility currency to pay for use of the Ethereum platform as the world computer.

Unlike Bitcoin, which has a very limited scripting language, Ethereum is designed to be a general-purpose, programmable blockchain that runs a virtual machine capable of executing code of arbitrary and unbounded complexity. Where Bitcoin’s Script language is intentionally constrained to simple true/false evaluation of spending conditions, Ethereum’s language is Turing complete, meaning that Ethereum can function as a general-purpose computer.

In September 2022, Ethereum further distinguished itself from Bitcoin with The Merge upgrade, transitioning its consensus model from proof of work (PoW) to proof of stake (PoS). This important change not only underlines Ethereum’s commitment to reducing its environmental impact—aligning with its innovative vision—but also enhances its scalability and security features.

Components of a Blockchain

The components of an open, public blockchain are (usually) as follows:

- A P2P network connecting participants and propagating transactions and blocks of verified transactions, based on a standardized “gossip” protocol

- Messages, in the form of transactions, representing state transitions

- A set of consensus rules governing what constitutes a transaction and what makes for a valid state transition

- A state machine that processes transactions according to the consensus rules

- A chain of cryptographically secured blocks that acts as a journal of all the verified and accepted state transitions

- A consensus algorithm that decentralizes control over the blockchain by forcing participants to cooperate in the enforcement of the consensus rules

- A game-theory-sound incentivization scheme (e.g., PoW costs plus block rewards) to economically secure the state machine in an open environment

- One or more open source software implementations of these components (“clients”)

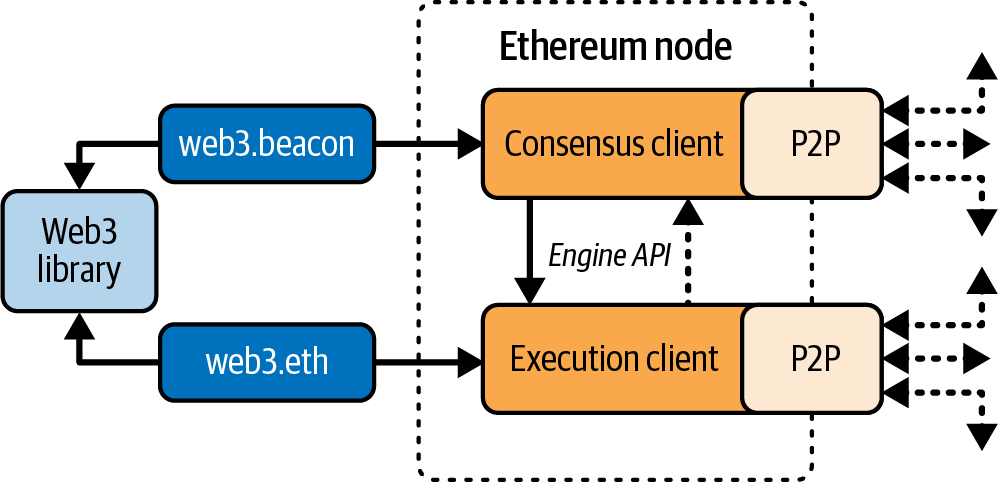

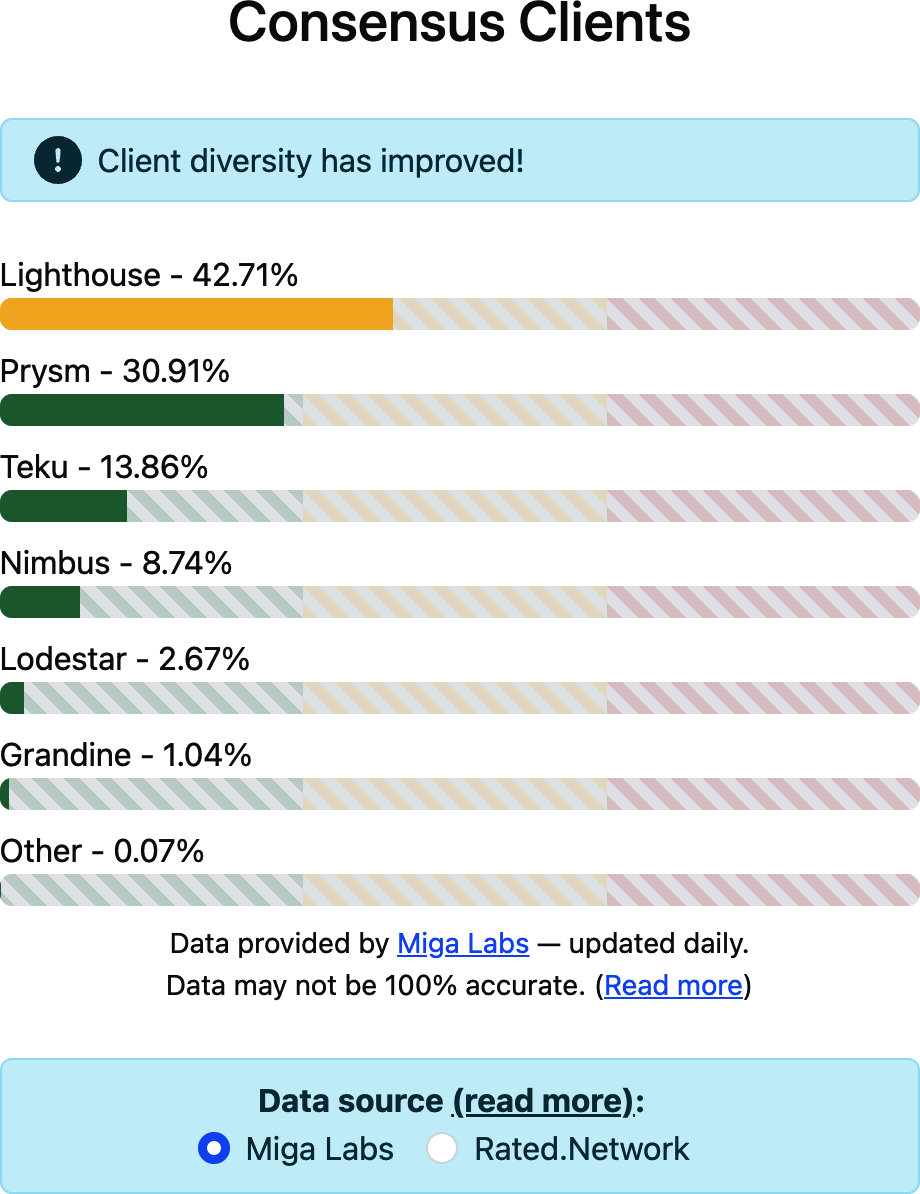

All or most of these components are usually combined in a single software client. For example, in Bitcoin, the reference implementation is developed by the Bitcoin Core open source project and implemented as the Bitcoin client. Initially, Ethereum also required a single client before its transition to PoS. However, Ethereum now utilizes two distinct clients: one for consensus and another for execution. Instead of a reference implementation, Ethereum relies on a reference specification: a mathematical description detailed in the “Yellow Paper”, which has been consistently updated throughout Ethereum’s development. The Ethereum community is currently transitioning toward a reference specification written in Python for both the consensus and the execution clients. A number of clients have been built according to the reference specification. We will dive deeper into this topic in Chapter 3.

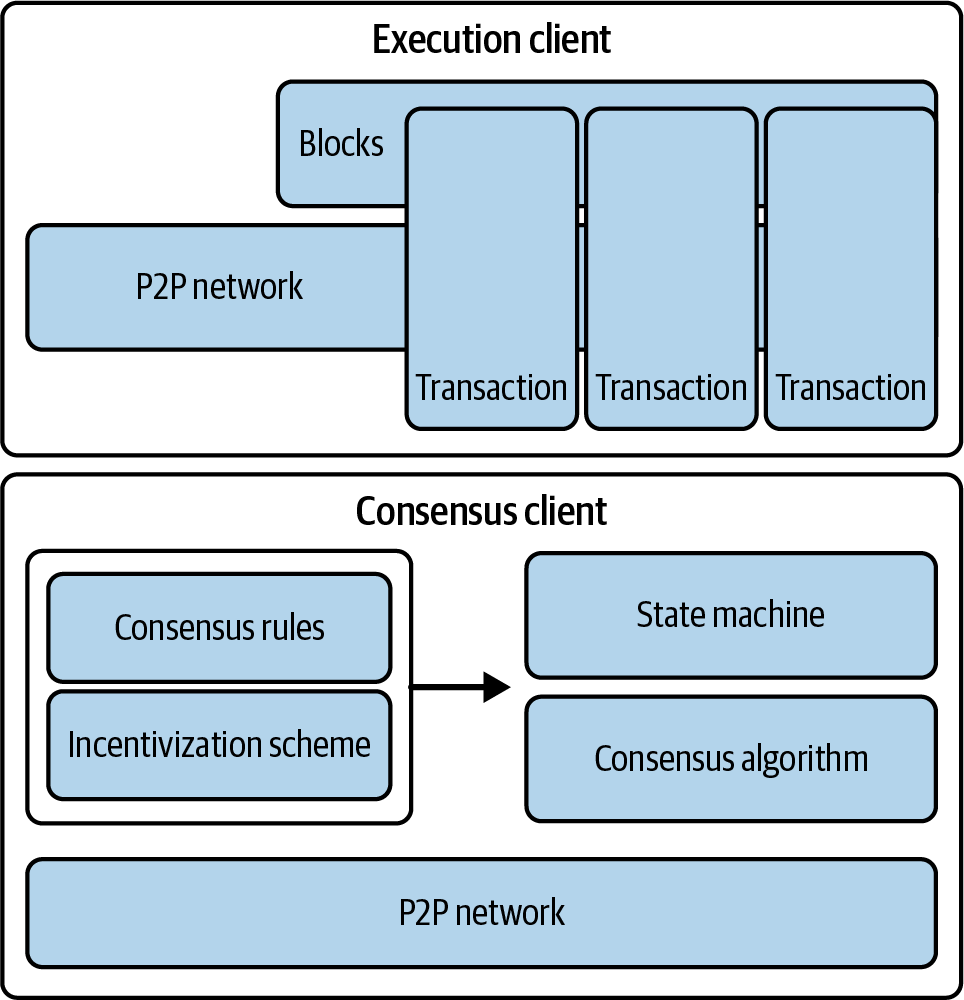

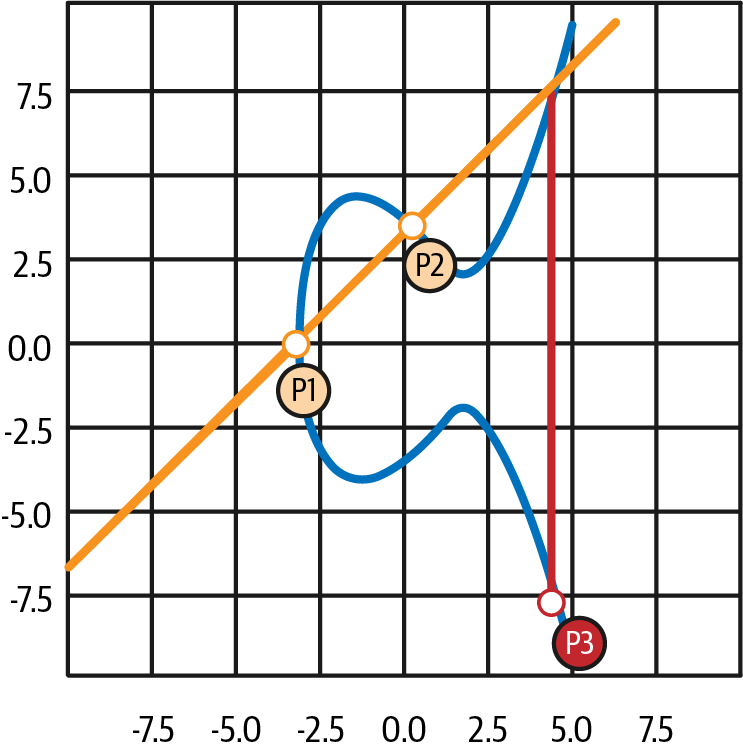

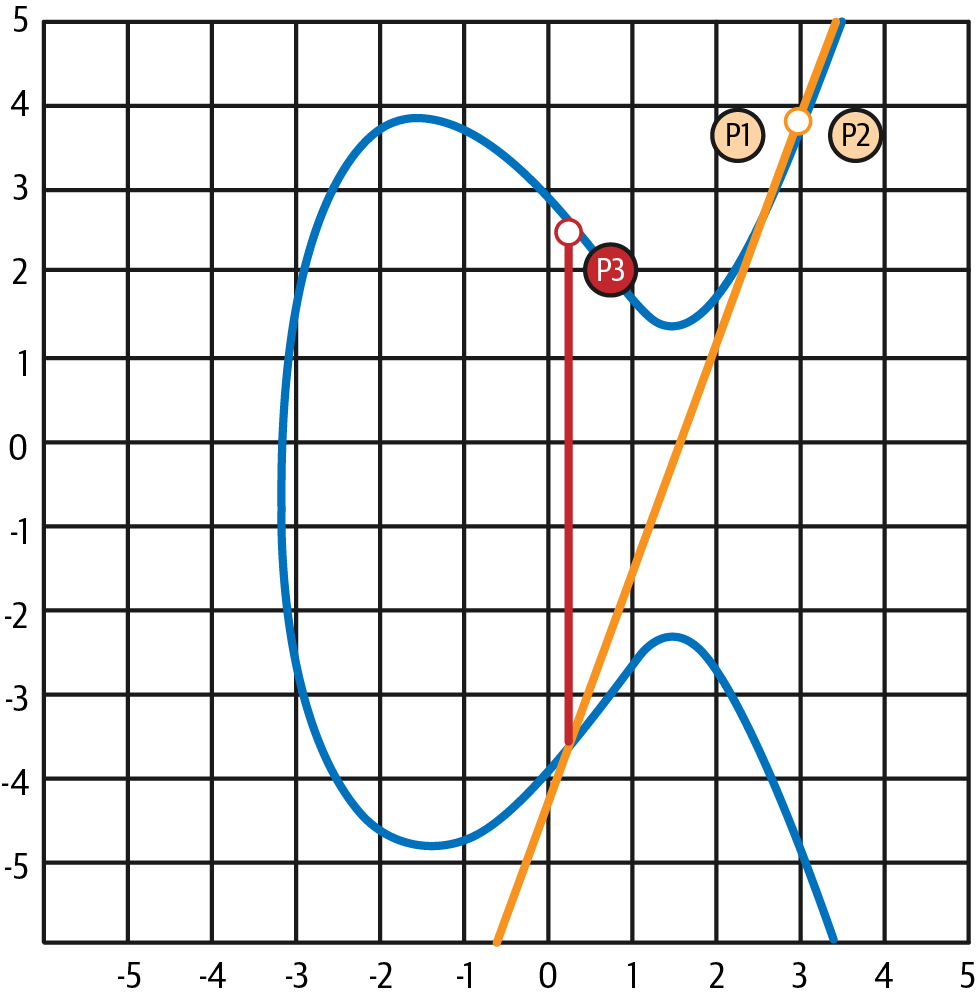

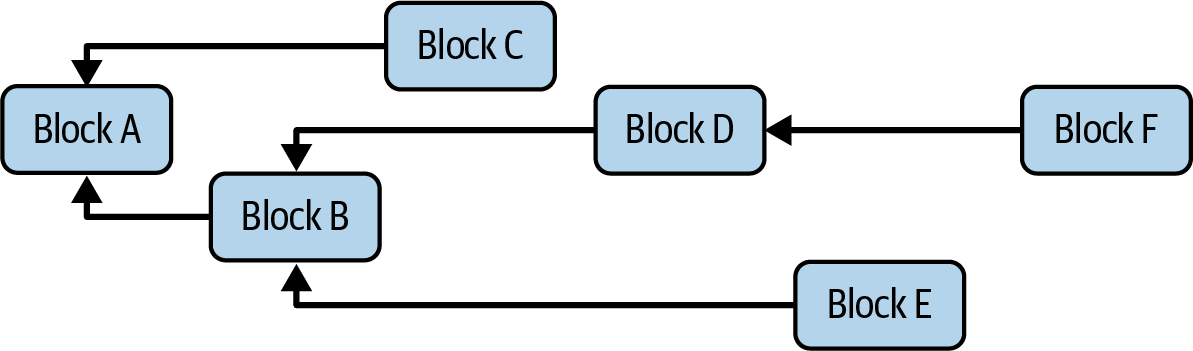

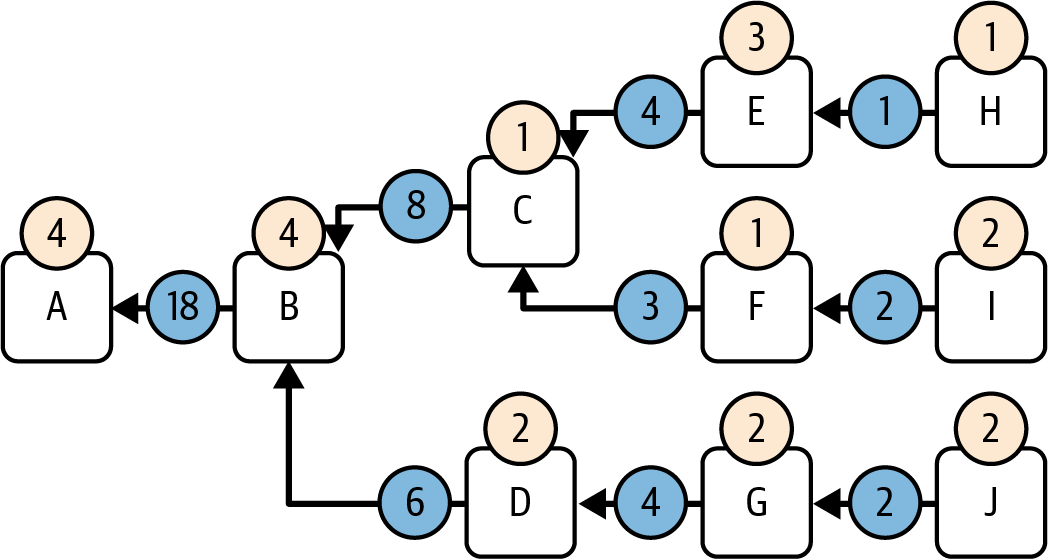

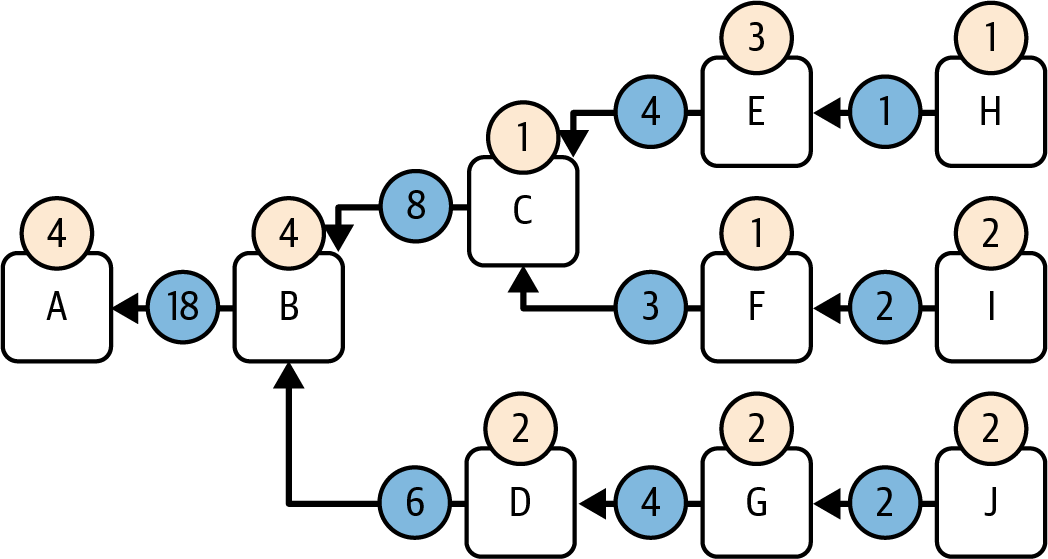

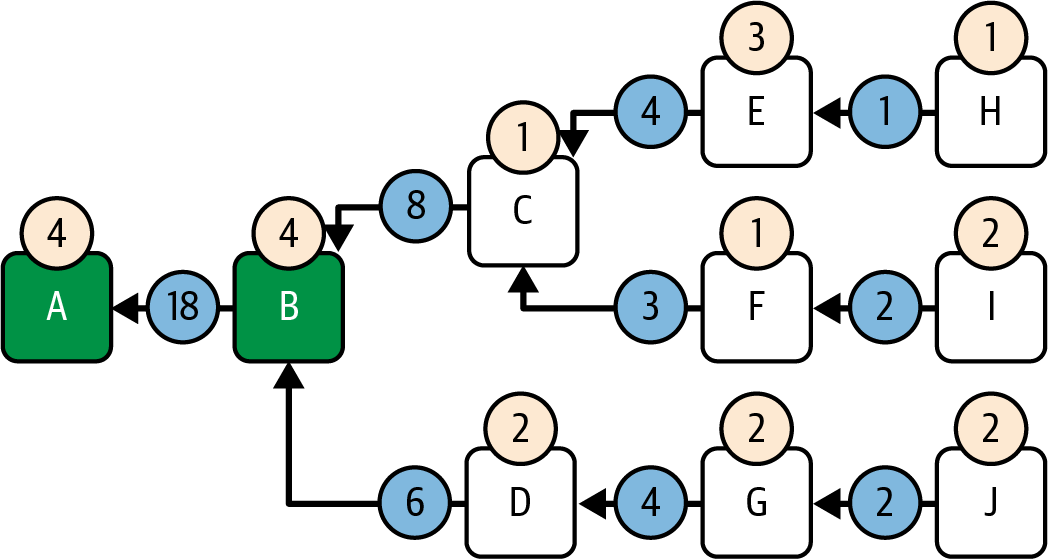

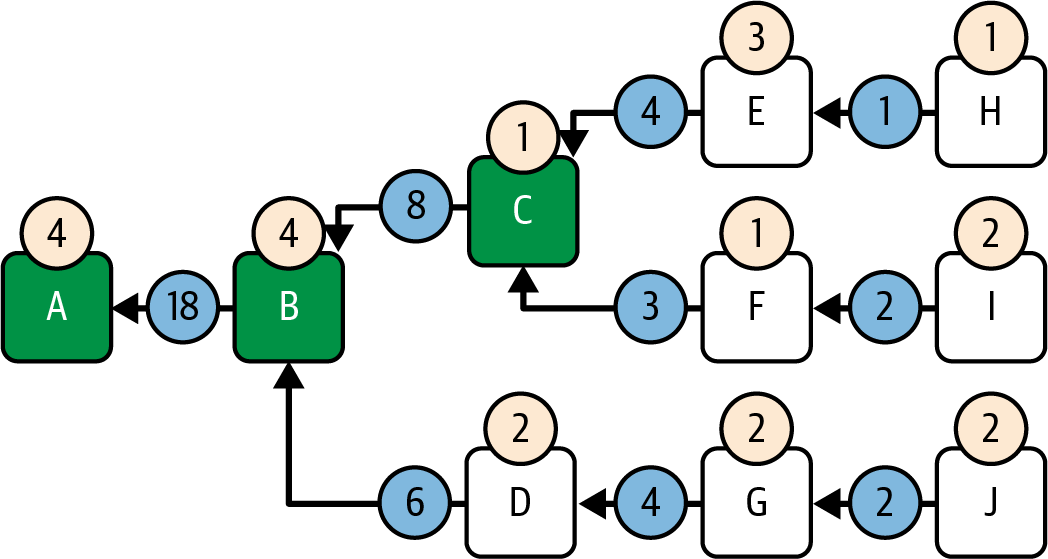

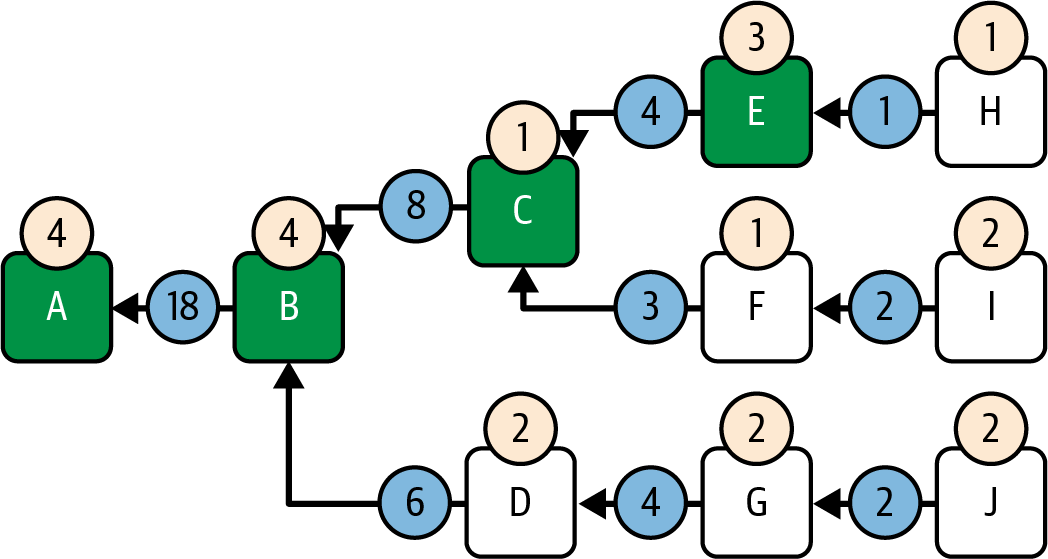

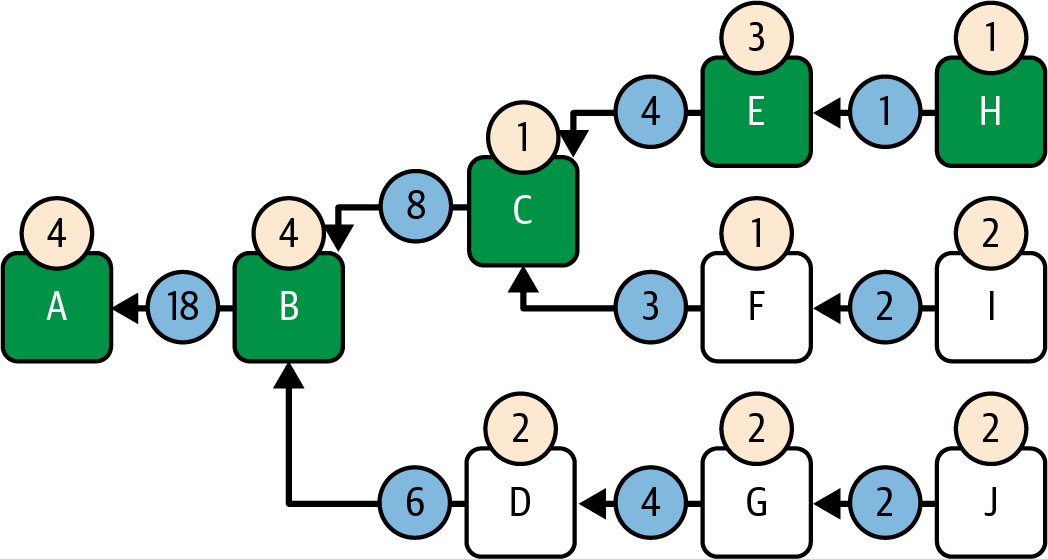

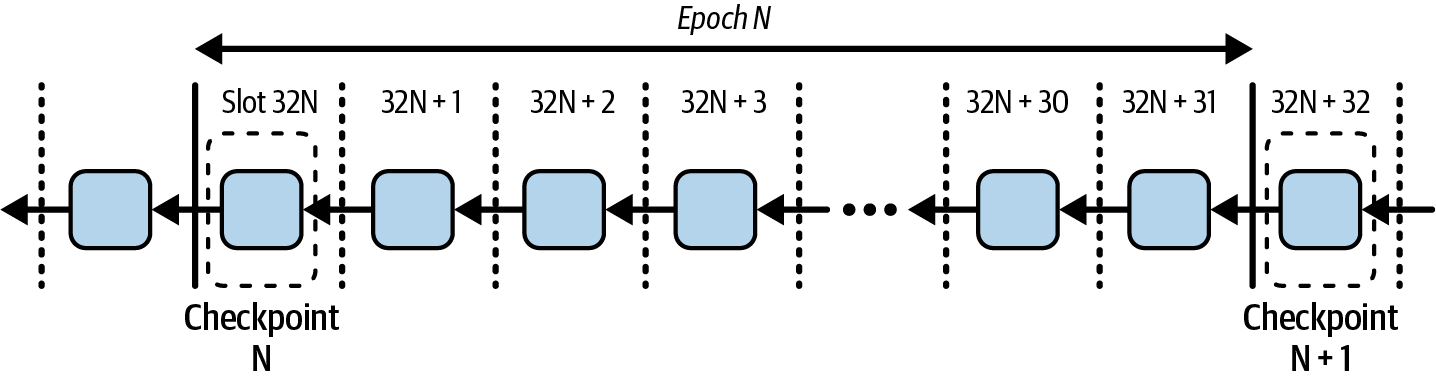

Figure 1-1 shows a graphical representation of the blockchain components.

Figure 1-1. Components of a blockchain

In the past, we used the term blockchain to represent all the components listed as a shorthand reference to the combination of technologies that encompass all the characteristics described. Today, however, there are a huge variety of blockchains with different properties. We need qualifiers to help us understand the characteristics of the blockchain in question, such as *open,*public, global, decentralized, neutral, and censorship resistant, to identify the important emergent characteristics of a “blockchain” system that these components allow.

Not all blockchains are created equal. Despite the huge amount of property they show, we can broadly categorize blockchains into permissioned versus permissionless and public versus private:

Permissionless

Permissionless blockchains, like Bitcoin and Ethereum, are accessible to anyone. These decentralized networks allow anyone to join, participate in the consensus process, and read and write data, promoting trust through transparency.

Permissioned

Permissioned blockchains restrict access, allowing only authorized participants to join the network and perform certain actions.

Public

Public blockchains are decentralized and open to everyone, allowing broad participation in network activities and ensuring transparency through widespread distribution and consensus mechanisms.

Private

Private blockchains limit access to a specific group of participants, often within organizations or among trusted partners.

The Birth of Ethereum

All great innovations solve real problems, and Ethereum is no exception. Ethereum was conceived at a time when people recognized the power of the Bitcoin model and were trying to move beyond cryptocurrency applications. But developers faced a conundrum: they either needed to build on top of Bitcoin or start a new blockchain. Building on Bitcoin meant living within the intentional constraints of the network and trying to find workarounds. The limited set of transaction types, data types, and sizes of data storage seemed to restrict the kinds of applications that could run directly on Bitcoin; anything else needed additional off-chain layers, and that immediately negated many of the advantages of using a public blockchain. For projects that required more freedom and flexibility while staying on chain, a new blockchain was the only option. But that meant a lot of work: bootstrapping all the infrastructure elements, exhaustive testing, and so on.

Toward the end of 2013, Vitalik Buterin, a young programmer and Bitcoin enthusiast, started thinking about further extending the capabilities of Bitcoin and Mastercoin (an overlay protocol that extended Bitcoin to offer rudimentary smart contracts). In October of that year, Buterin proposed a more generalized approach to the Mastercoin team, one that allowed flexible and scriptable (but not Turing complete) contracts to replace the specialized contract language of Mastercoin. Although the Mastercoin team was impressed, this proposal was too radical a change to fit into their development roadmap.

In December 2013, Buterin started sharing a whitepaper that outlined the idea behind Ethereum: a Turing-complete, general-purpose blockchain. A few dozen people saw this early draft and offered feedback, helping Buterin evolve the proposal.

Both of the original authors of this book, Andreas M. Antonopoulos and Dr. Gavin Wood, received an early draft of the whitepaper and commented on it. Antonopoulos was intrigued by the idea and asked Buterin many questions about the use of a separate blockchain to enforce consensus rules on smart contract execution and the implications of a Turing-complete language. Antonopoulos continued to follow Ethereum’s progress with great interest but was in the early stages of writing his book Mastering Bitcoin and did not participate directly in Ethereum until much later. Wood, however, was one of the first people to reach out to Buterin and offer to help with his C++ programming skills. Wood became Ethereum’s cofounder, co-designer, and CTO.

Buterin recounts in his “A Prehistory of the Ethereum Protocol” post:

This was the time when the Ethereum protocol was entirely my own creation. From here on, however, new participants started to join the fold. By far the most prominent on the protocol side was Gavin Wood.

Wood can also be largely credited for the subtle change in vision from seeing Ethereum as a platform for building programmable money, with blockchain-based contracts that can hold digital assets and transfer them according to preset rules, to viewing it as a general-purpose computing platform. This started with subtle changes in emphasis and terminology, and later this influence became stronger with the increasing emphasis on the “Web3” ensemble, which saw Ethereum as one piece of a suite of decentralized technologies, with the other two being Whisper and Swarm. Starting in December 2013, Buterin and Wood refined and evolved the idea, together building the protocol layer that became Ethereum.

Ethereum’s founders were thinking about a blockchain without a specific purpose, which could support a broad variety of applications by being programmed. The idea was that by using a general-purpose blockchain like Ethereum, a developer could program their particular application without having to implement the underlying mechanisms of P2P networks, blockchains, consensus algorithms, and the like. Ethereum abstracts away those details and offers a deterministic, secure environment for writing decentralized applications. This shift in thinking didn’t just make development easier; it fundamentally expanded what blockchains could do. It laid the groundwork for entirely new sectors like decentralized finance, NFTs, and decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), which wouldn’t have been feasible with earlier single-purpose blockchains.

Much like Satoshi Nakamoto (the pseudonymous developer of Bitcoin), Buterin and Wood didn’t just invent a new technology; they combined new inventions with existing technologies in a novel way and delivered the prototype code to prove their ideas to the world.

The founders worked for years to build and refine their vision. And on July 30, 2015, the first Ethereum block was mined. The world’s computer started serving the world.

Note

Vitalik Buterin’s article “A Prehistory of the Ethereum Protocol” was published in September 2017 and provides a fascinating first-person view of Ethereum’s earliest moments.

Ethereum’s Stages of Development

Ethereum’s development was planned over four distinct stages, with major changes occurring at each stage. A stage may include subreleases, known as hard forks, that change functionality in a way that is not backward compatible.

The four main development stages are codenamed Frontier, Homestead, Metropolis, and Serenity. At the time of writing, we are in the last stage: Serenity. The Serenity stage has been further broken down into six substages codenamed The Merge, The Surge, The Scourge, The Verge, The Purge, and The Splurge.

Let’s now dive into the four development stages and describe their main purposes:

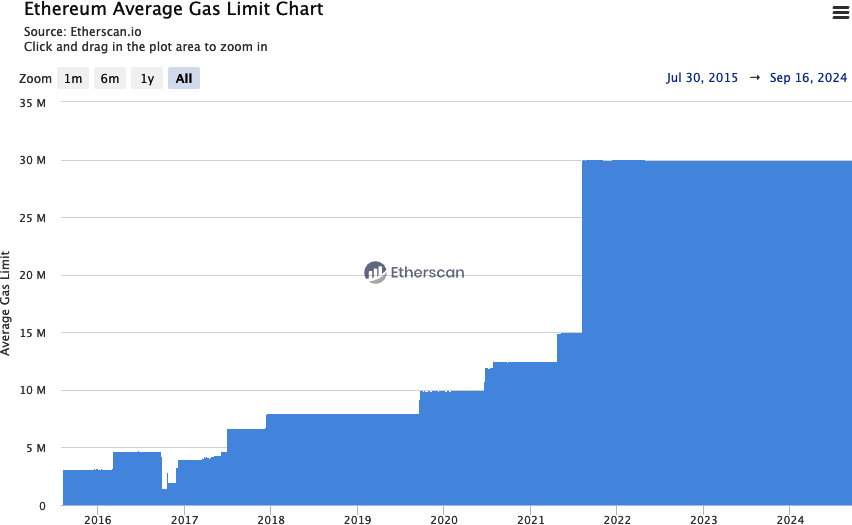

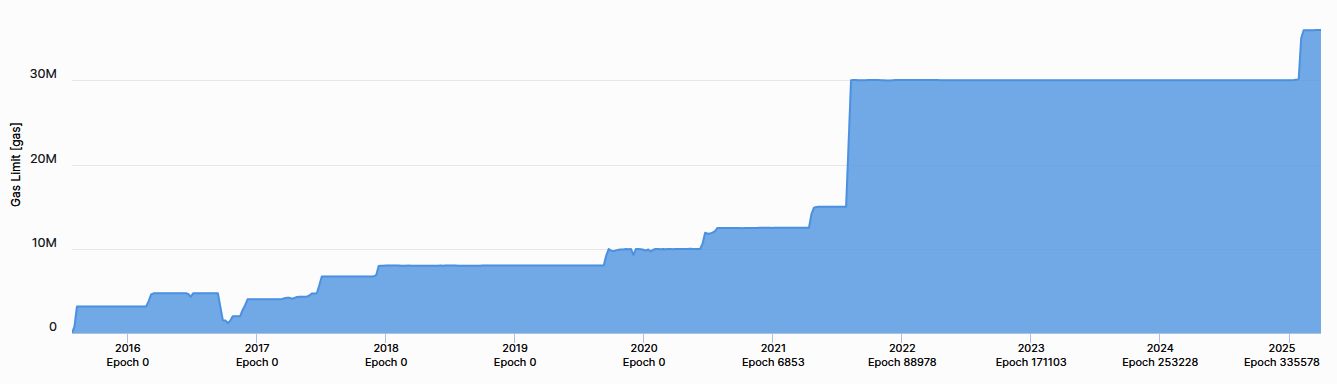

Frontier (July 30, 2015)

Launched at Genesis (when the first Ethereum block was mined), Frontier prepared the foundation for miners and developers by enabling the setup of mining rigs, the initiation of ETH token trading, and the testing of decentralized applications (DApps) in a minimal network setting. Initially, blocks had a gas limit of five thousand, but that was lifted in September 2015, allowing for transactions and introducing the “difficulty bomb.” Ethereum’s difficulty bomb is a mechanism designed to exponentially increase the difficulty of mining over time, ultimately making it infeasible. This incentivizes the transition from the original PoW consensus to the more energy-efficient PoS model currently in use.

Homestead (March 14, 2016)

Initiated at block 1,150,000, Homestead made Ethereum safer and more stable through key protocol updates (EIP-2, EIP-7, and EIP-8). These upgrades enhanced developer friendliness and paved the way for further protocol improvements, although the network remained in the beta phase.

Metropolis (October 16, 2017)

Starting at block 4,370,000, Metropolis aimed to increase network functionality, fostering DApp creation and overall network utility. Significant forks like Byzantium, Constantinople, and Istanbul during this phase optimized gas costs, enhanced security, and introduced layer-2 (L2) scaling solutions. Byzantium reduced mining rewards and implemented cryptographic provisions, while Constantinople further optimized gas costs and allowed interactions with uncreated addresses. Istanbul made the network more resilient against distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks and introduced zero-knowledge cryptographic proofs (zk-SNARKs and STARKs) for improved scalability and privacy. These enhancements collectively set the stage for Ethereum 2.0, representing the final phase of Ethereum 1.0.

Serenity (September 15, 2022)

Serenity, commonly known as Ethereum 2.0, represents a major upgrade aimed at transforming Ethereum from a PoW to a PoS consensus mechanism. Serenity focuses on making Ethereum more sustainable and capable of handling a growing number of users and applications. This stage addresses critical issues like high energy consumption and network congestion, clearing the way for a more robust and efficient blockchain.

The Serenity upgrade is divided into several substages, each addressing specific aspects of the network’s evolution. While the main four development stages have been implemented sequentially, the five Serenity substages are being developed at the same time. This parallel approach is a strategic departure from the previous development method and is made possible because the foundational work laid down by the initial four stages was necessary for the simultaneous development of the Serenity substages. Each of these substages improves the Ethereum chain in a different aspect, unrelated to the others, enabling a more flexible and dynamic upgrade process:

The Merge

The Merge combines Ethereum’s mainnet with the Beacon Chain (the sidechain handling the PoS consensus), officially transitioning the network to PoS and reducing energy consumption significantly.

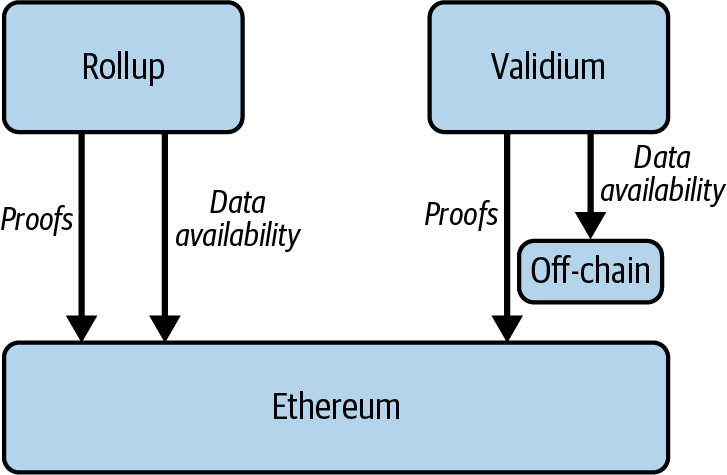

The Surge

The Surge introduces sharding, increasing Ethereum’s scalability by splitting the network into smaller, manageable pieces, which allows for more transactions per second.

The Scourge

The Scourge addresses issues of centralization and censorship resistance, ensuring that Ethereum remains a decentralized and open network.

The Verge

The Verge implements Verkle trees, reducing the data storage required for nodes and thus improving network efficiency and scalability.

The Purge

The Purge aims to reduce the historical data stored on Ethereum, simplifying node operation and lowering network congestion.

The Splurge

The Splurge includes various minor upgrades and optimizations to ensure that Ethereum runs smoothly and efficiently after all major changes are implemented.

Ethereum: A General-Purpose Blockchain

The original blockchain—namely, Bitcoin’s blockchain—tracks the state of units of Bitcoin and their ownership. You can think of Bitcoin as a distributed-consensus state machine, where transactions cause a global state transition, altering the ownership of coins. The state transitions are constrained by the rules of consensus, allowing all participants to (eventually) converge on a common (consensus) state of the system, after several blocks are mined.

Ethereum is also a distributed state machine. But instead of tracking only the state of currency ownership, Ethereum tracks the state transitions of a general-purpose data store—that is, a store that can hold any data expressible as a key-value tuple. A key-value data store holds arbitrary values, each referenced by some key: for example, the value “Mastering Ethereum” referenced by the key “Book Title.” In some ways, this serves the same purpose as the data-storage model of random-access memory (RAM) used by most general-purpose computers.

Ethereum has memory that stores both code and data, and it uses the Ethereum blockchain to track how this memory changes over time. Like a general-purpose, stored-program computer, Ethereum can load code into its state machine and run that code, storing the resulting state changes in its blockchain. Two of the critical differences from most general-purpose computers are that Ethereum state changes are governed by the rules of consensus and the state is distributed globally. Ethereum answers the question “What if we could track any arbitrary state and program the state machine to create a worldwide computer operating under consensus?”

Ethereum’s Components

In Ethereum, the components of a blockchain system (described in “Components of a Blockchain”) are, more specifically, as follows:

P2P network

Ethereum runs on the Ethereum main network, which is addressable on TCP port 30303, and runs a protocol called ÐΞVp2p.

Consensus rules

Ethereum’s original consensus protocol was Ethash, a PoW model defined in the reference specification: the “Yellow Paper.” It then evolved to PoS in September 2022 during The Merge upgrade (see Chapter 15).

Transactions

Ethereum transactions are network messages that include (among other things) a sender, a recipient, a value, and a data payload.

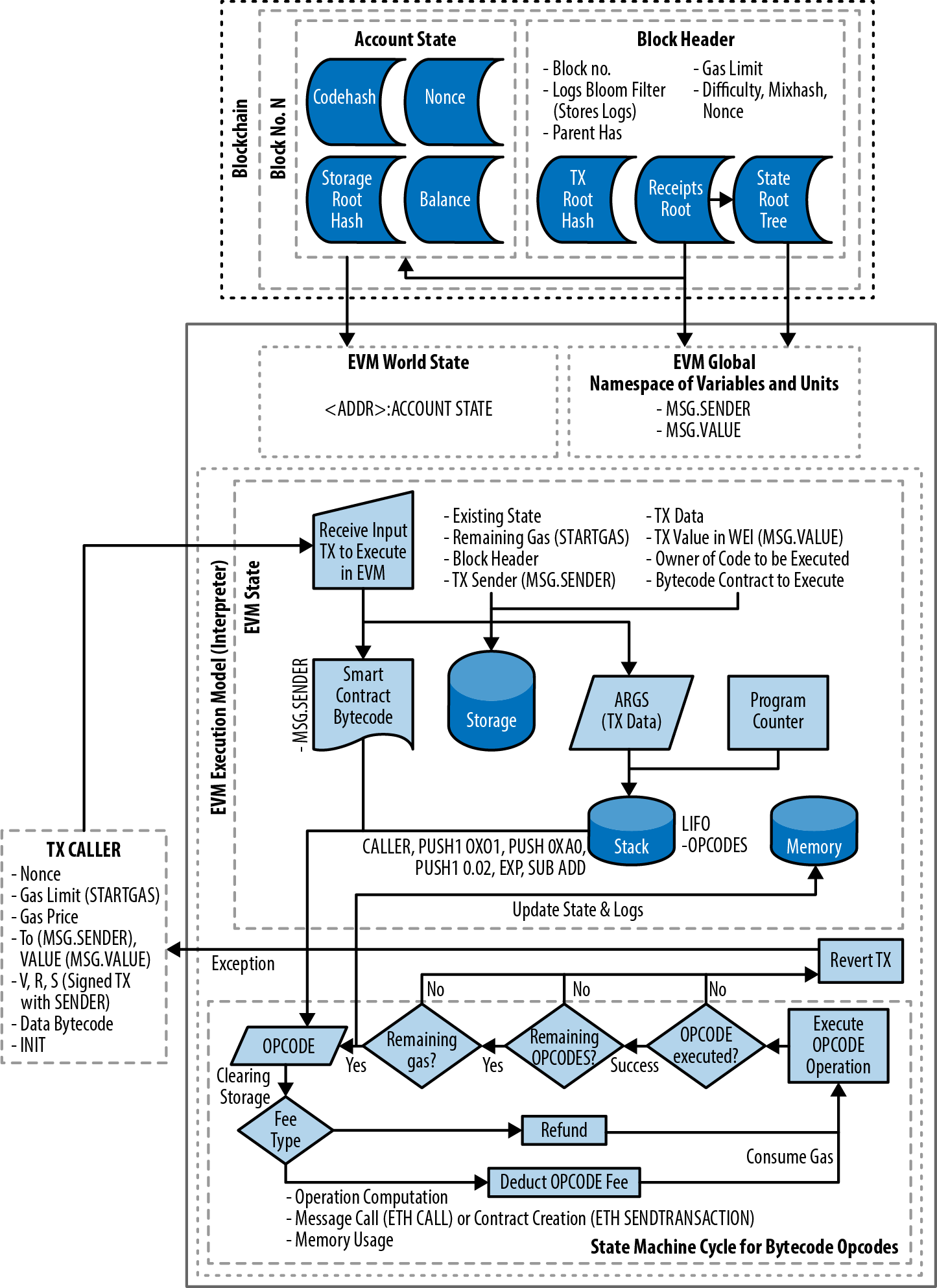

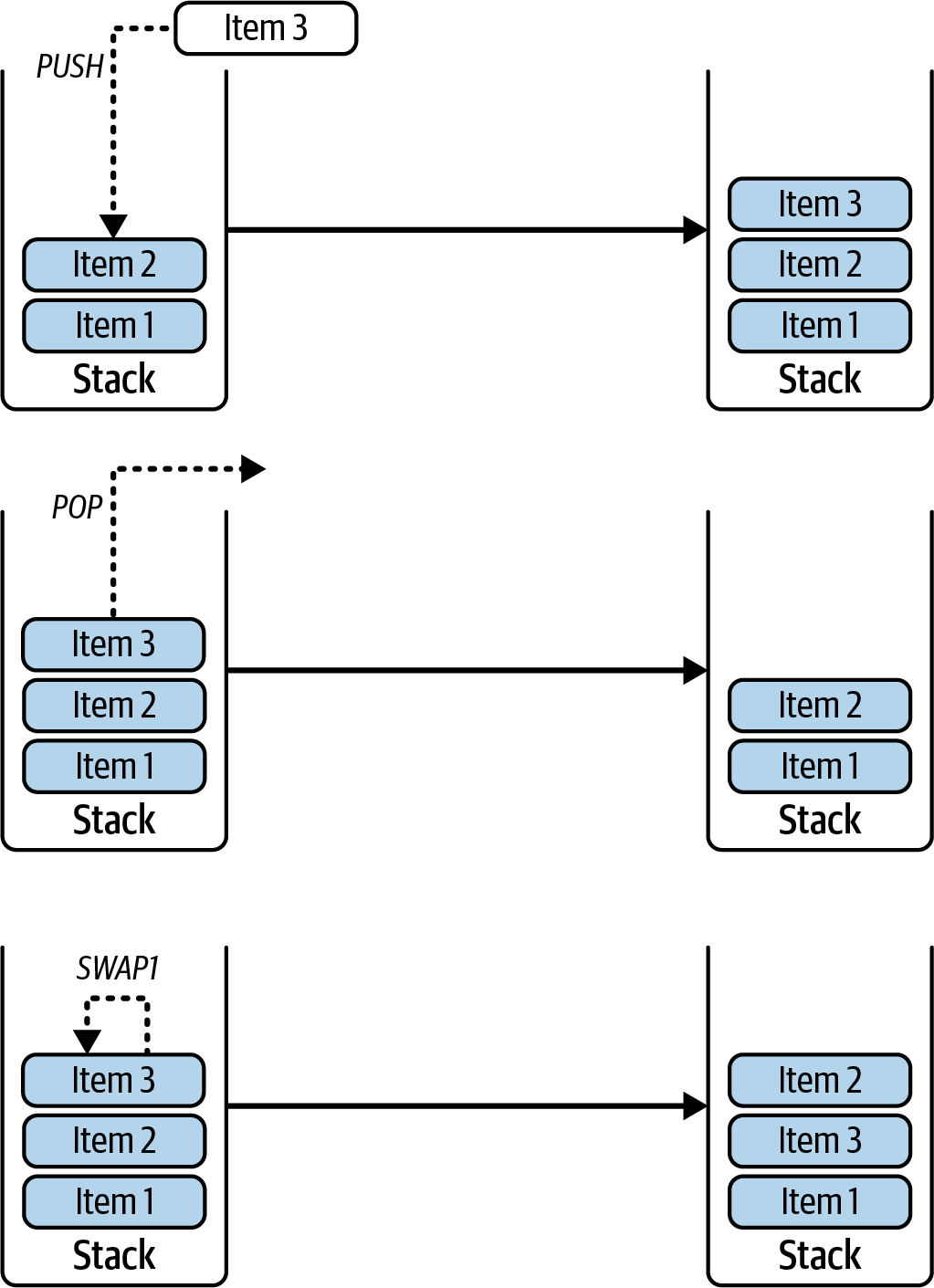

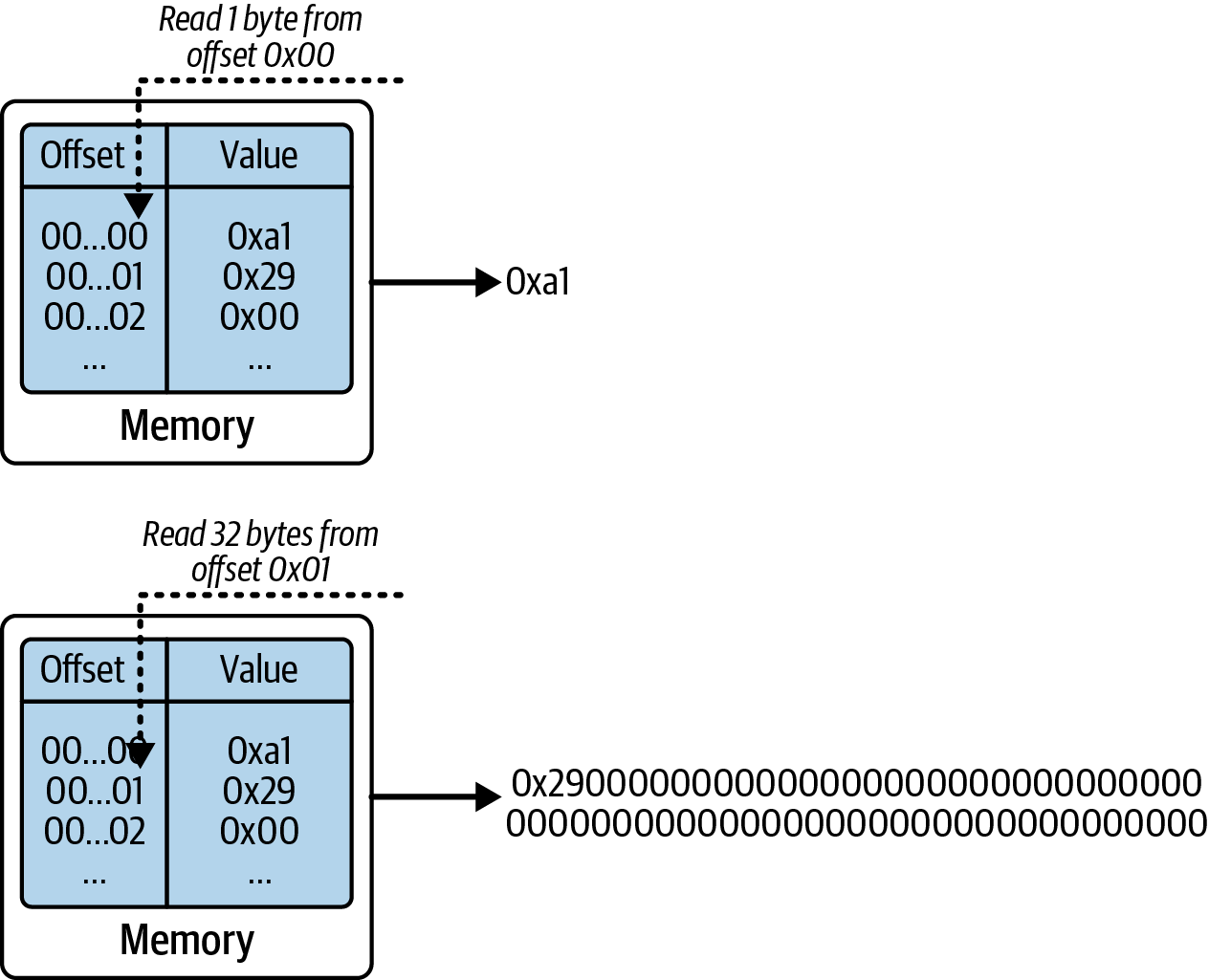

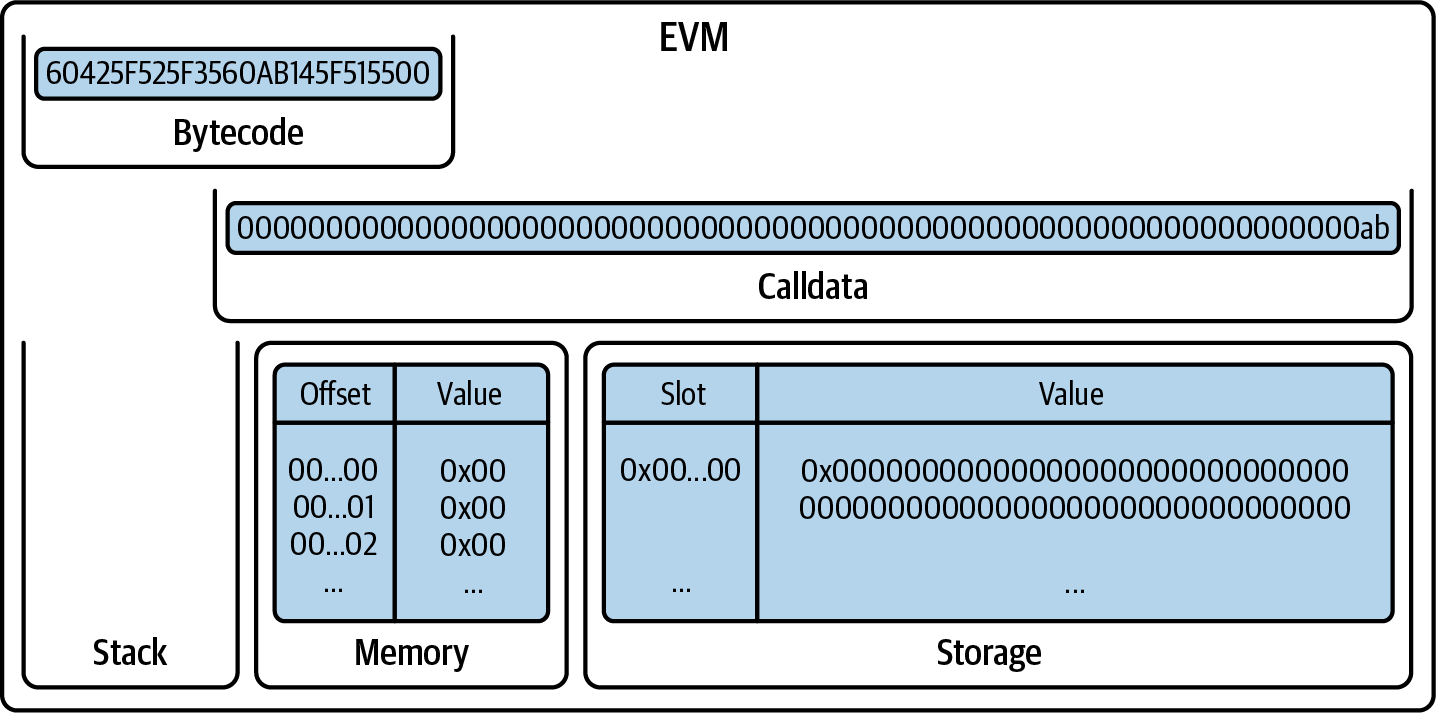

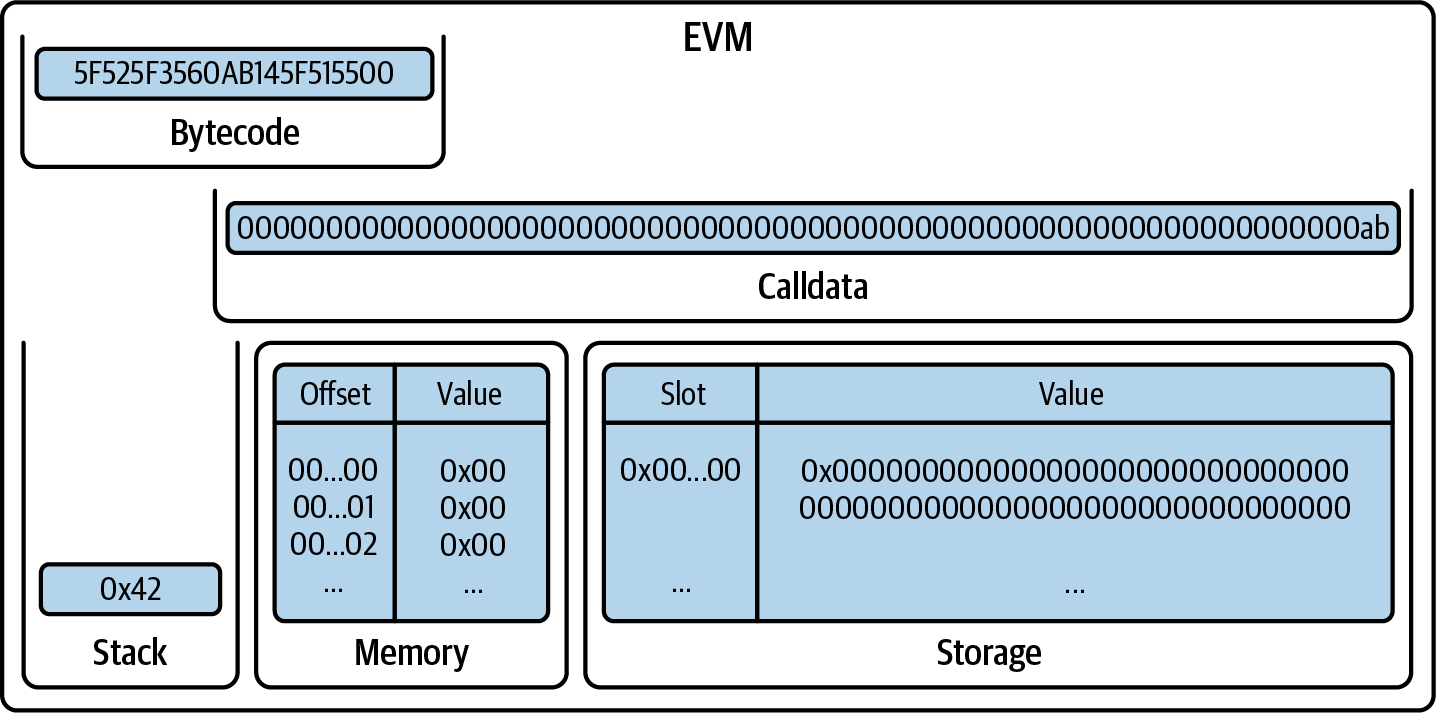

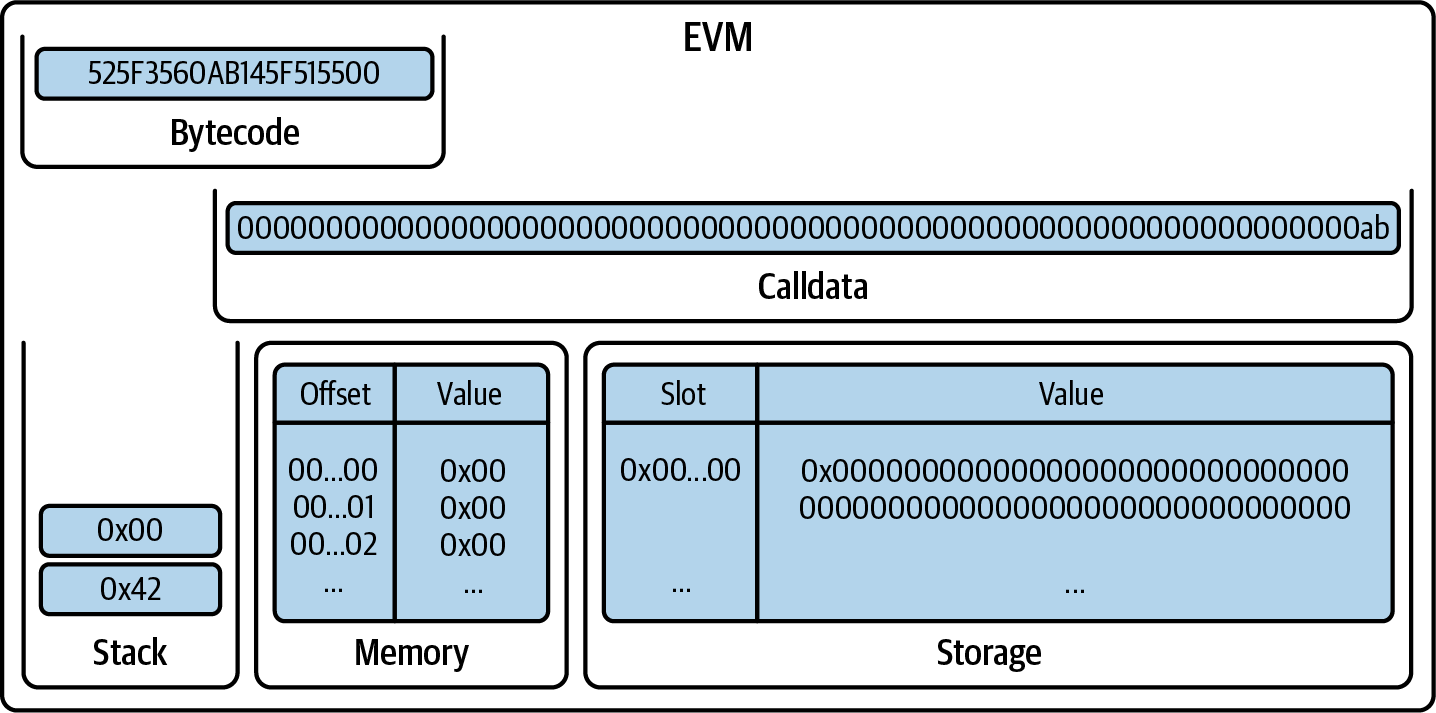

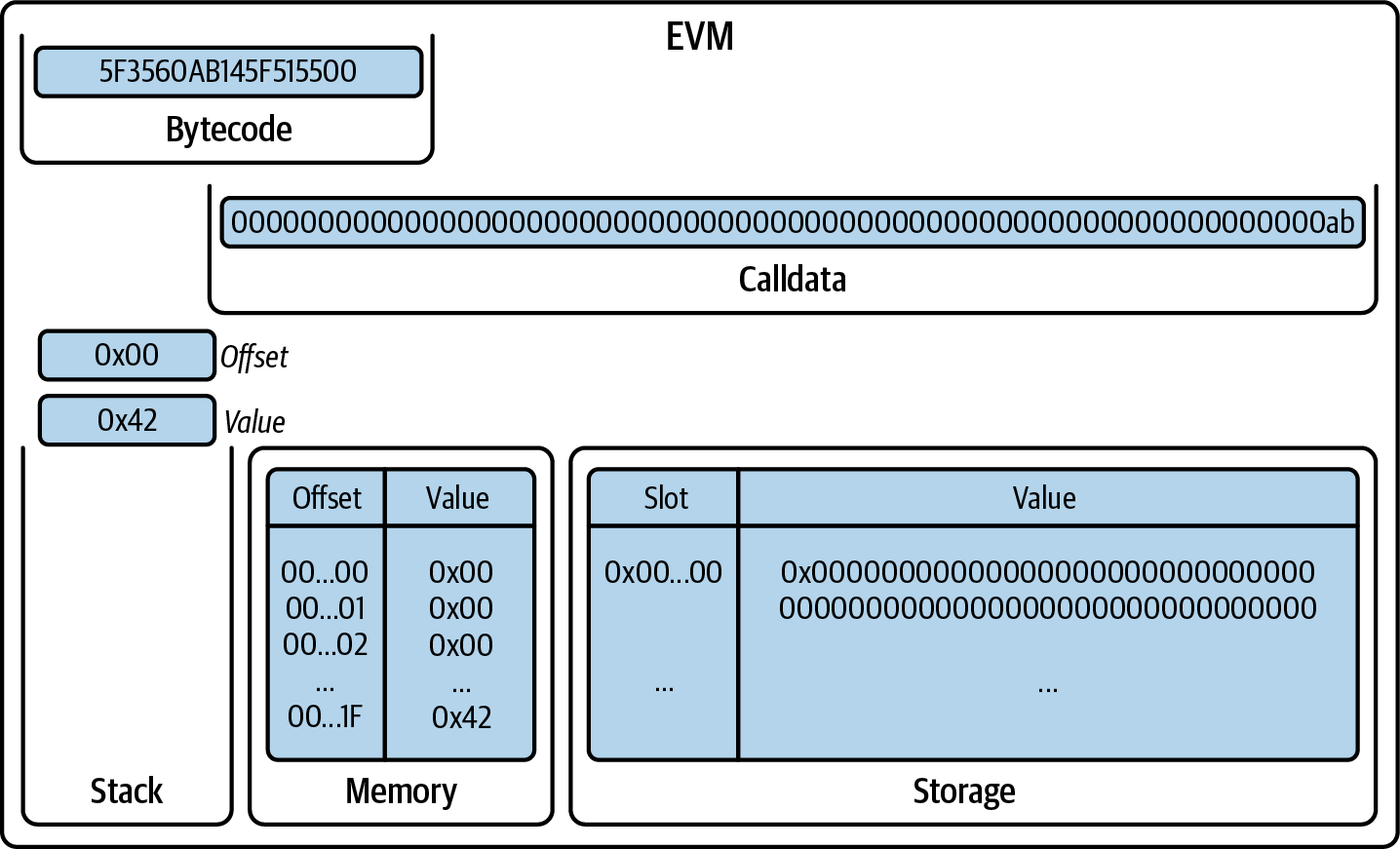

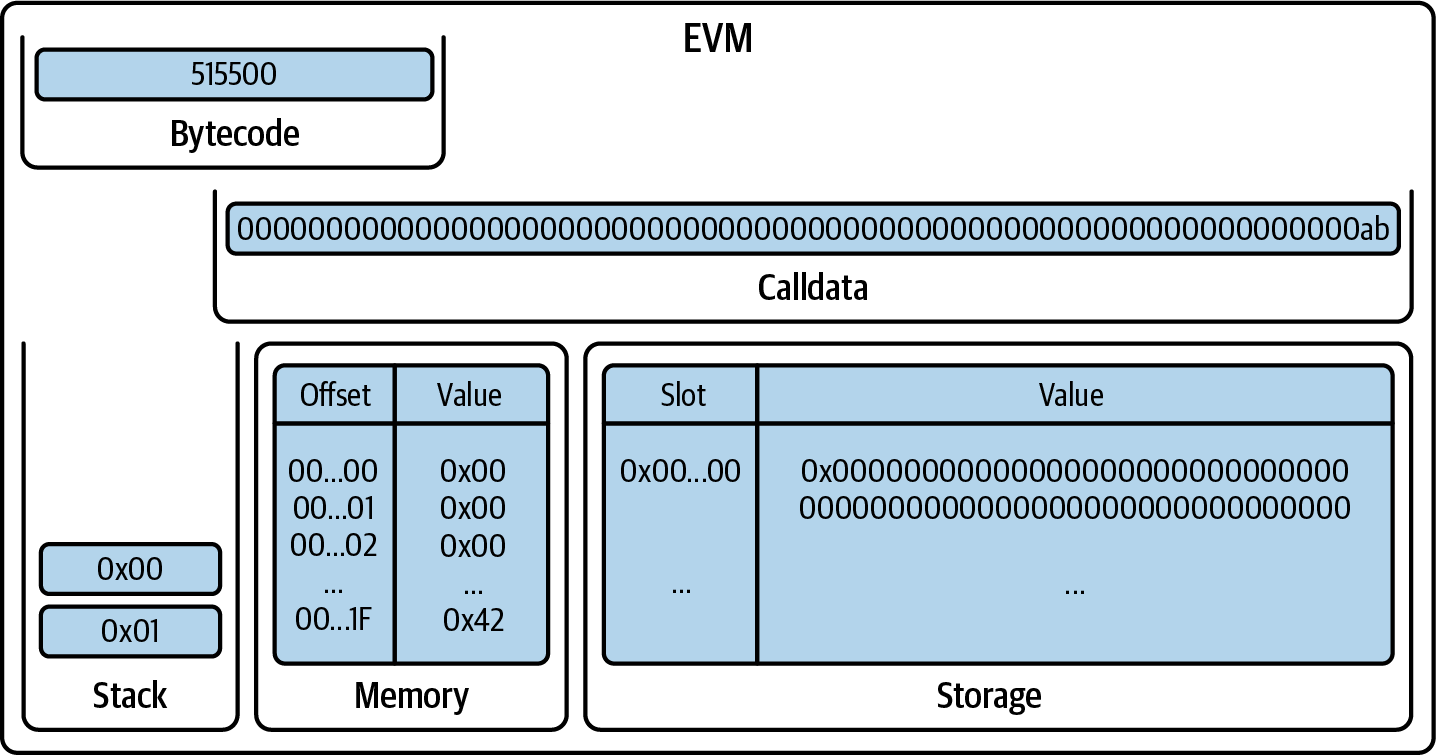

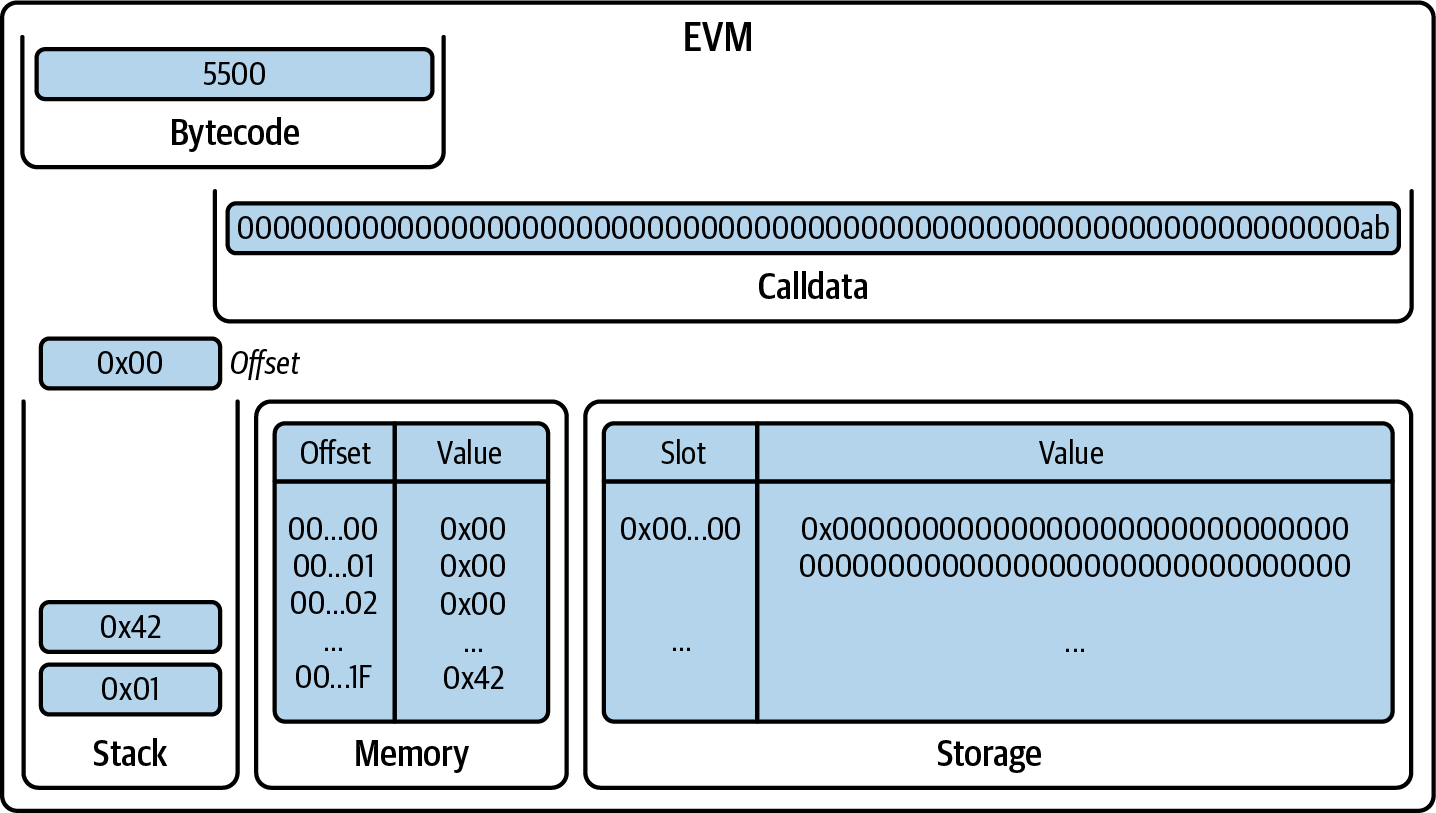

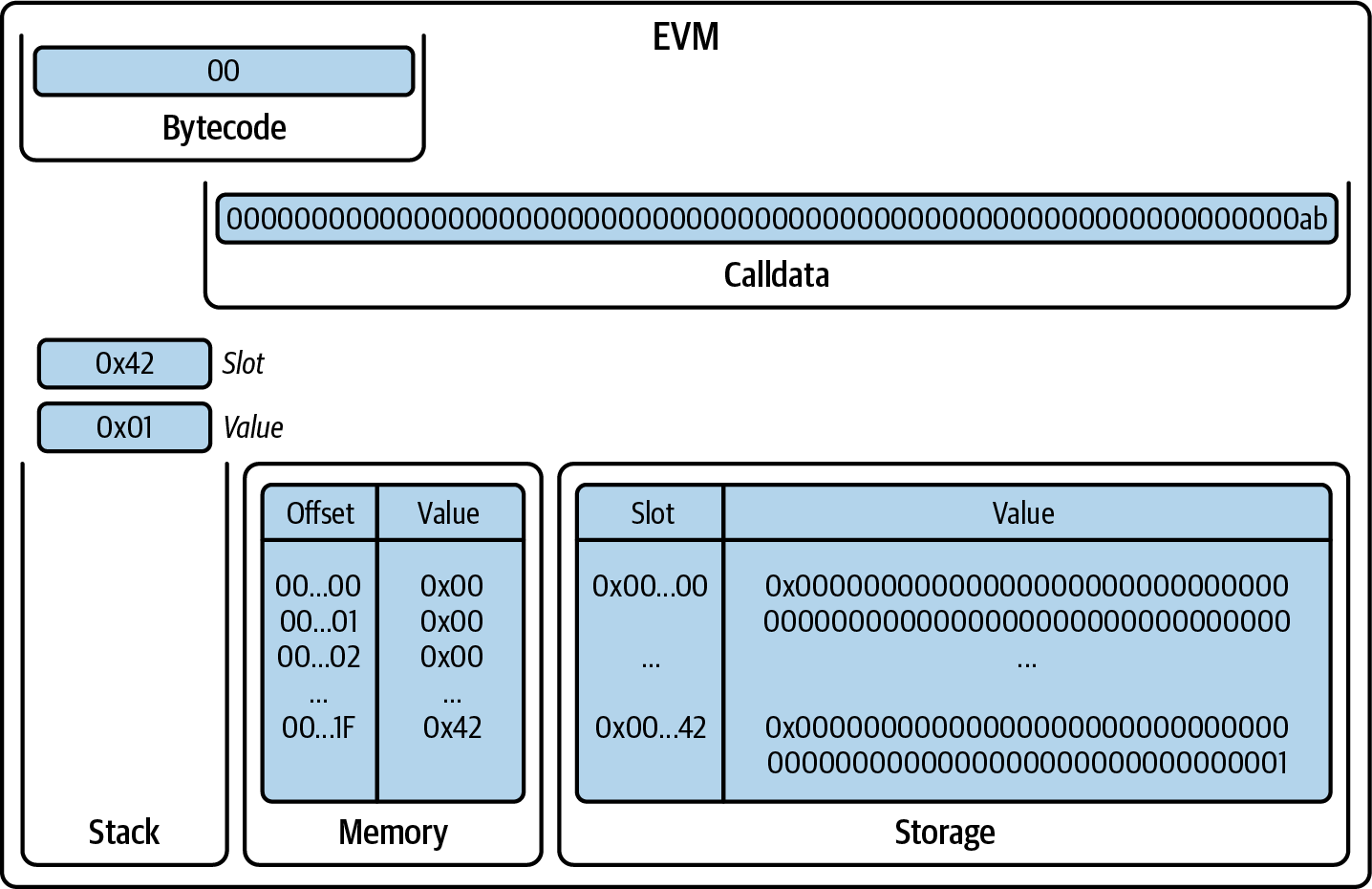

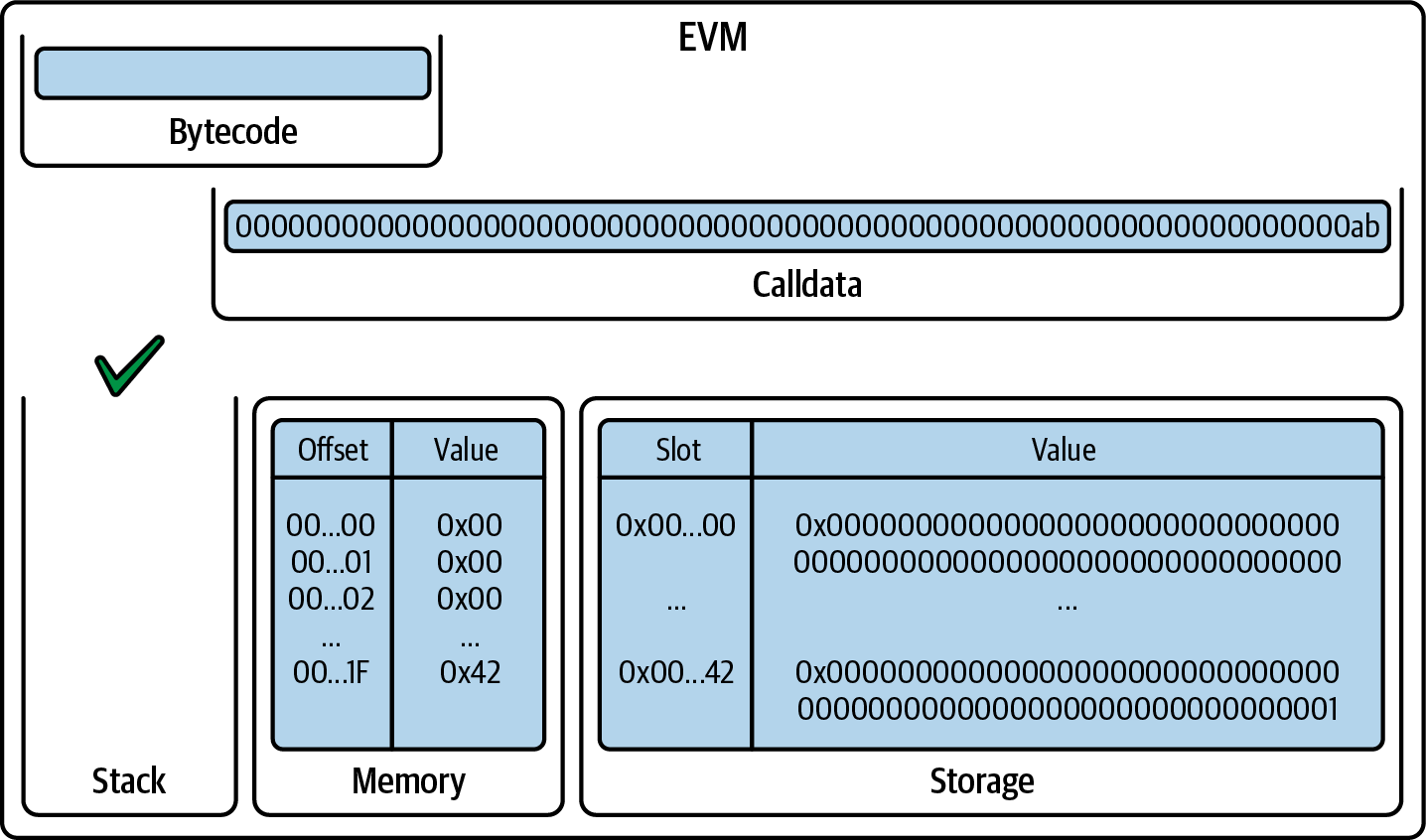

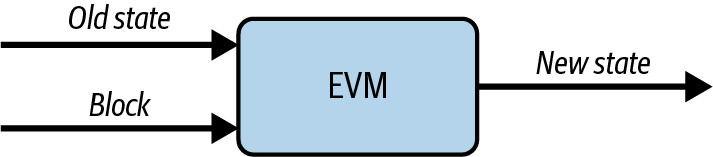

State machine

Ethereum state transitions are processed by the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), a stack-based virtual machine that executes bytecode (machine-language instructions). EVM programs called smart contracts are written in high-level languages (e.g., Solidity) and compiled to bytecode for execution on the EVM.

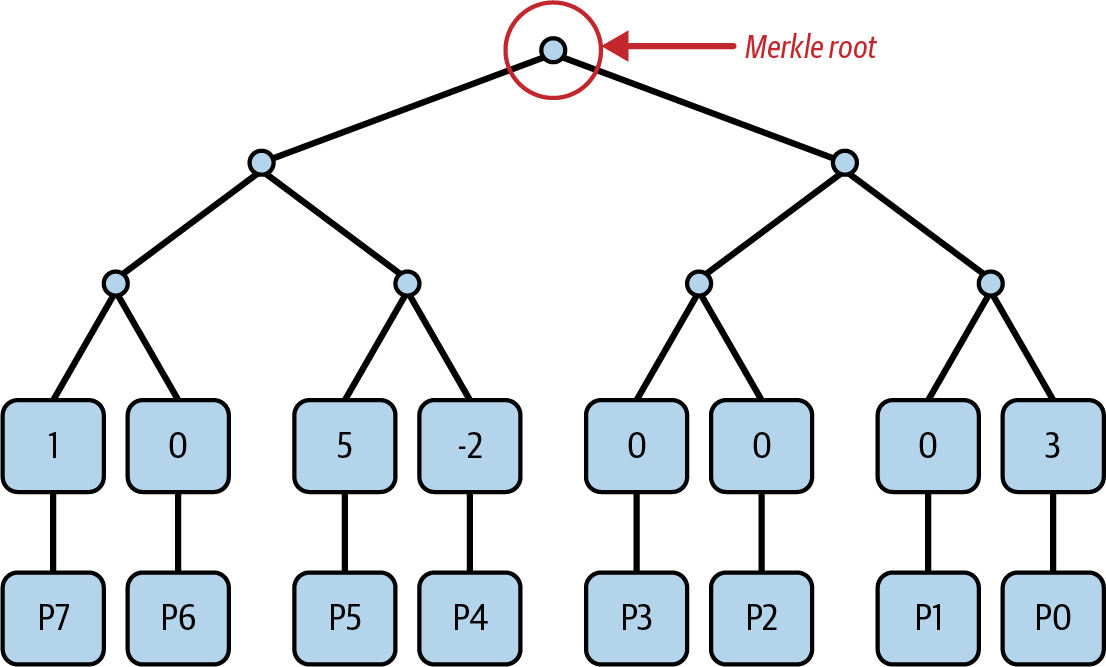

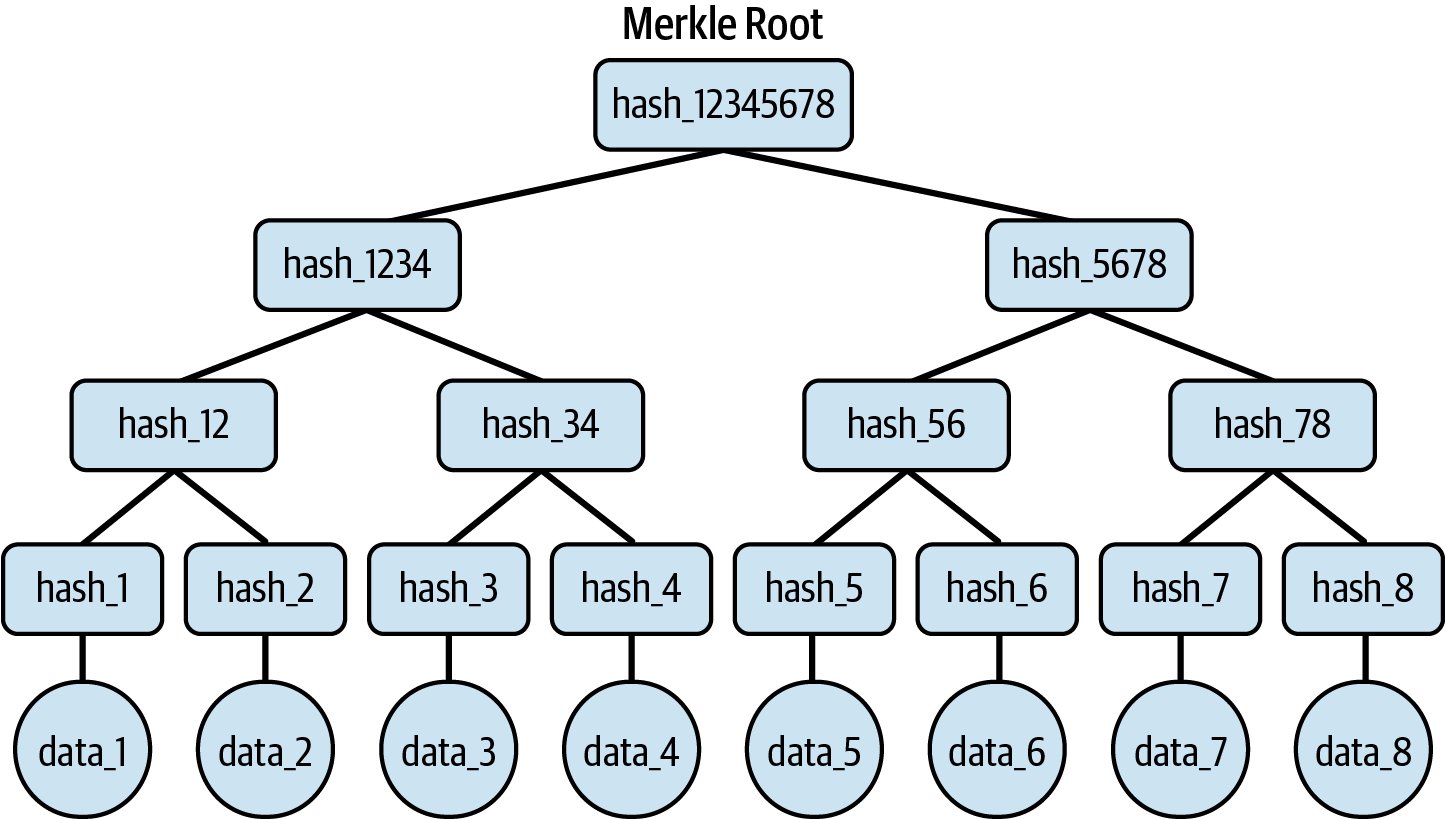

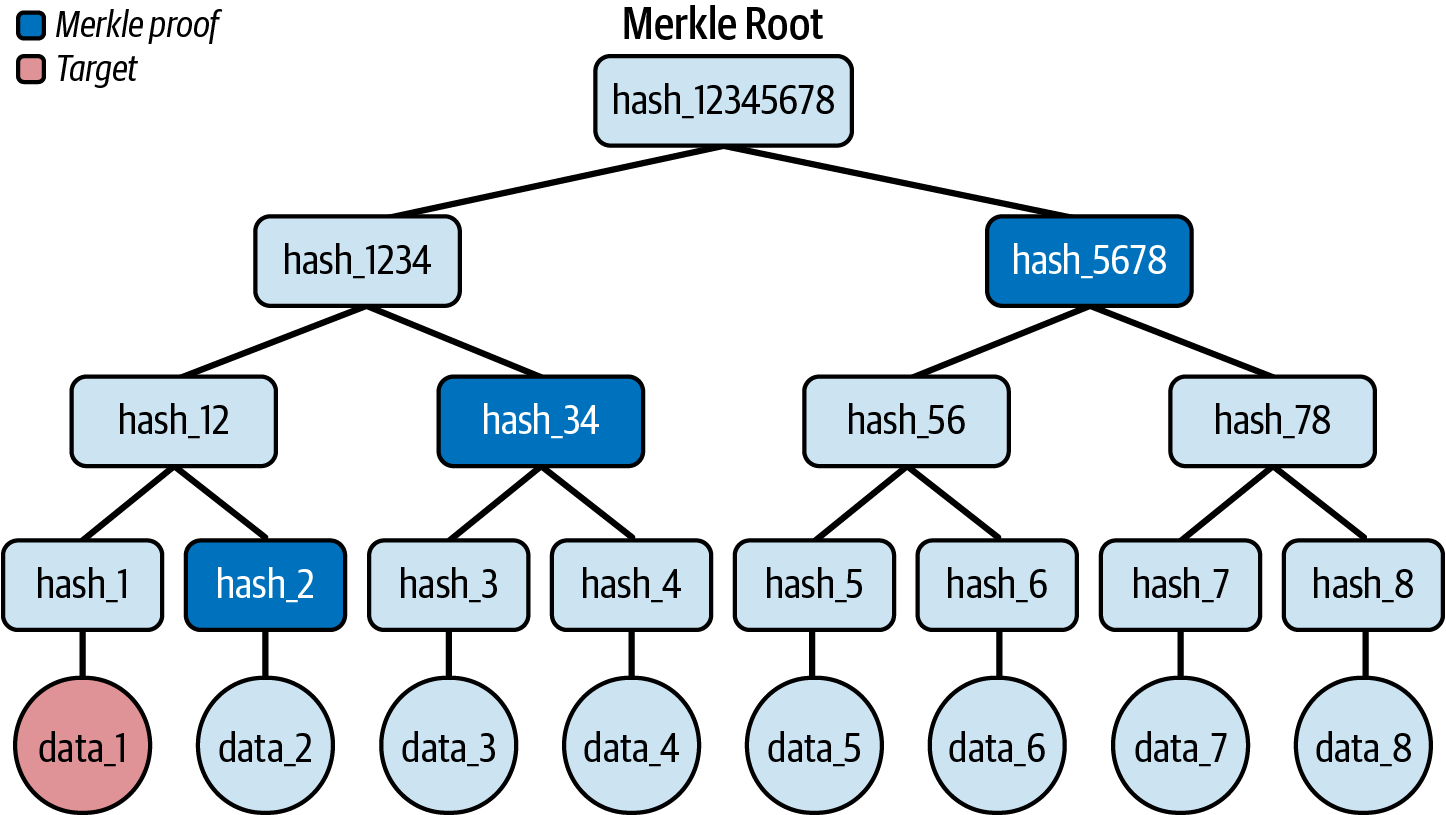

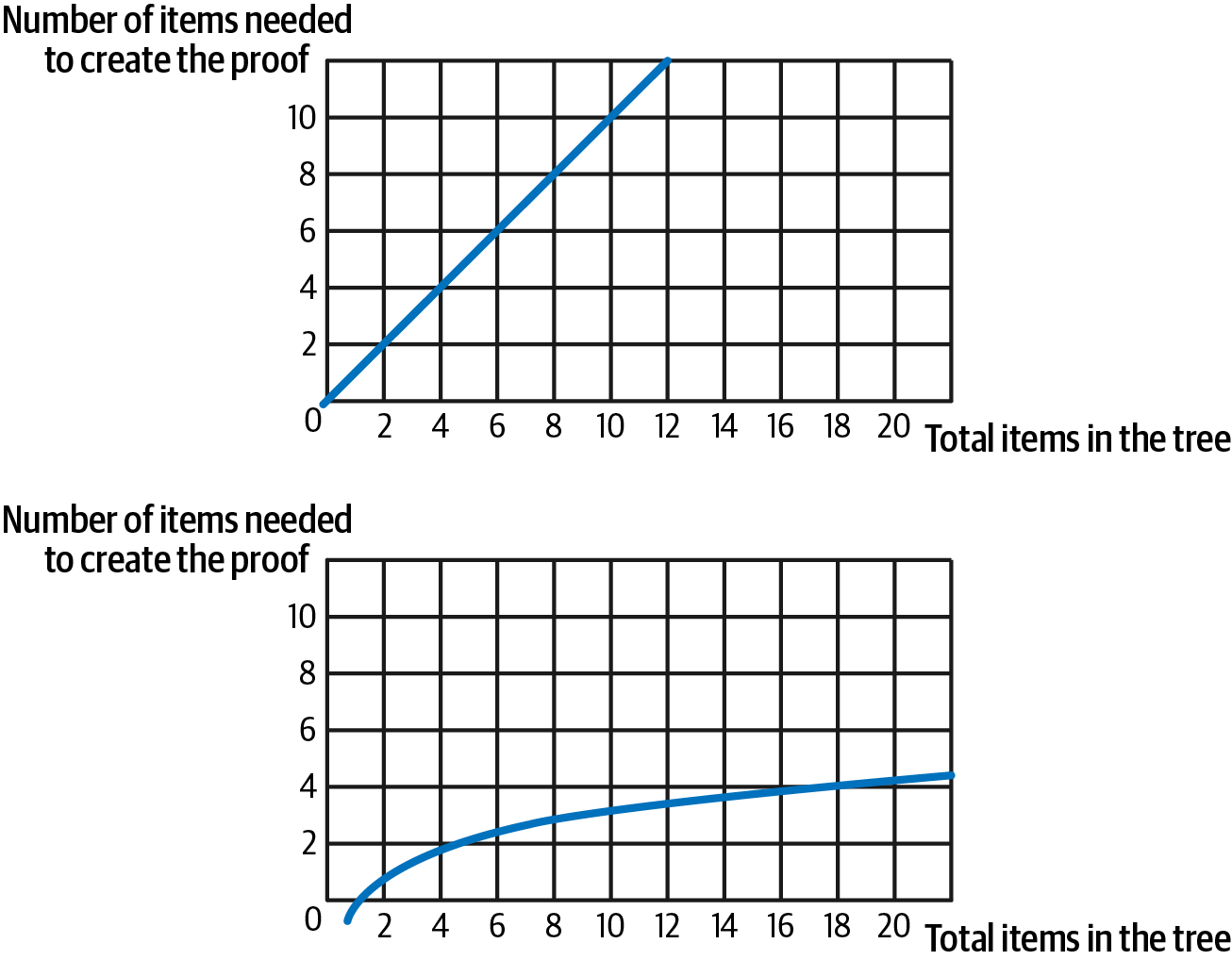

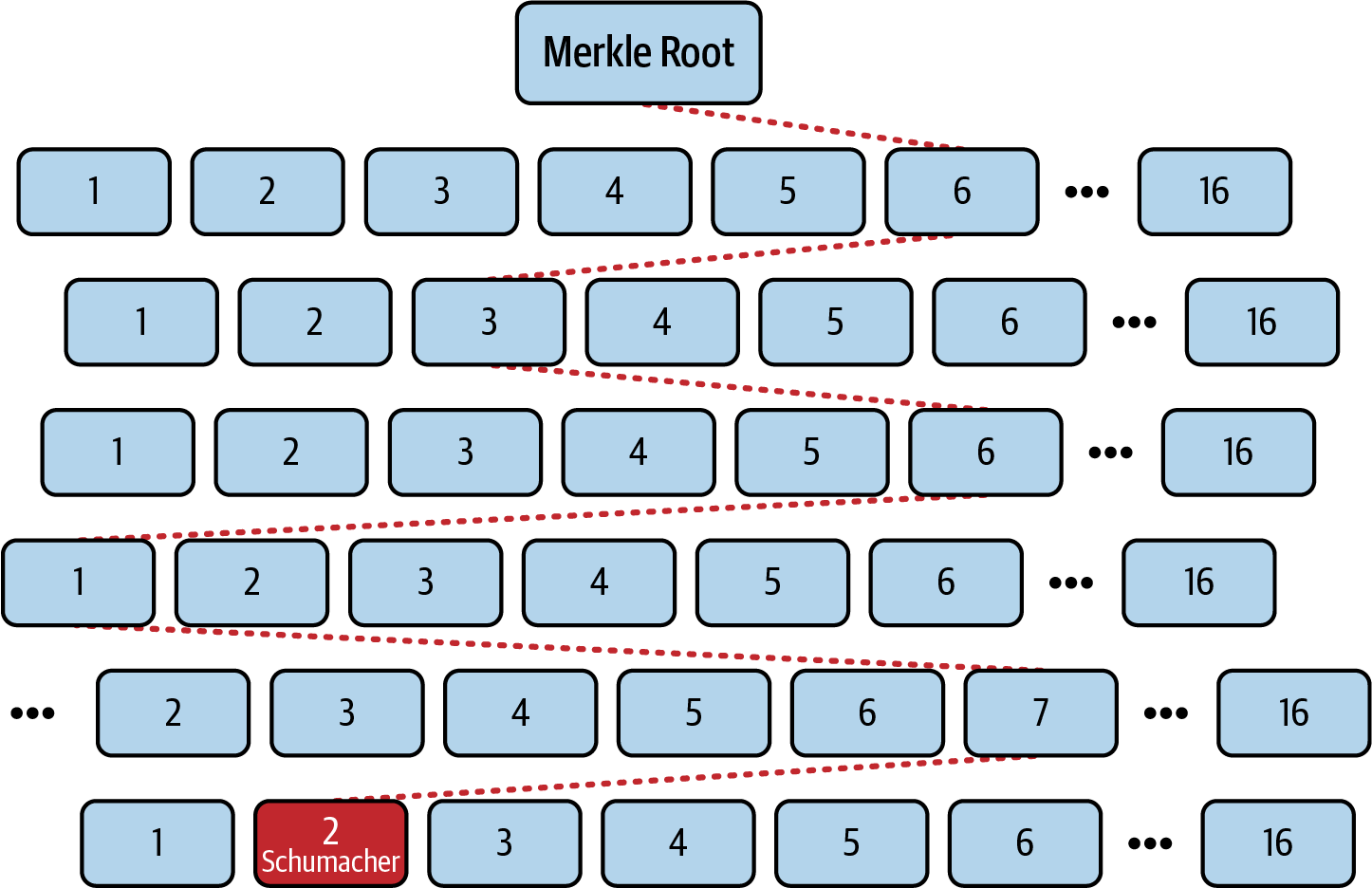

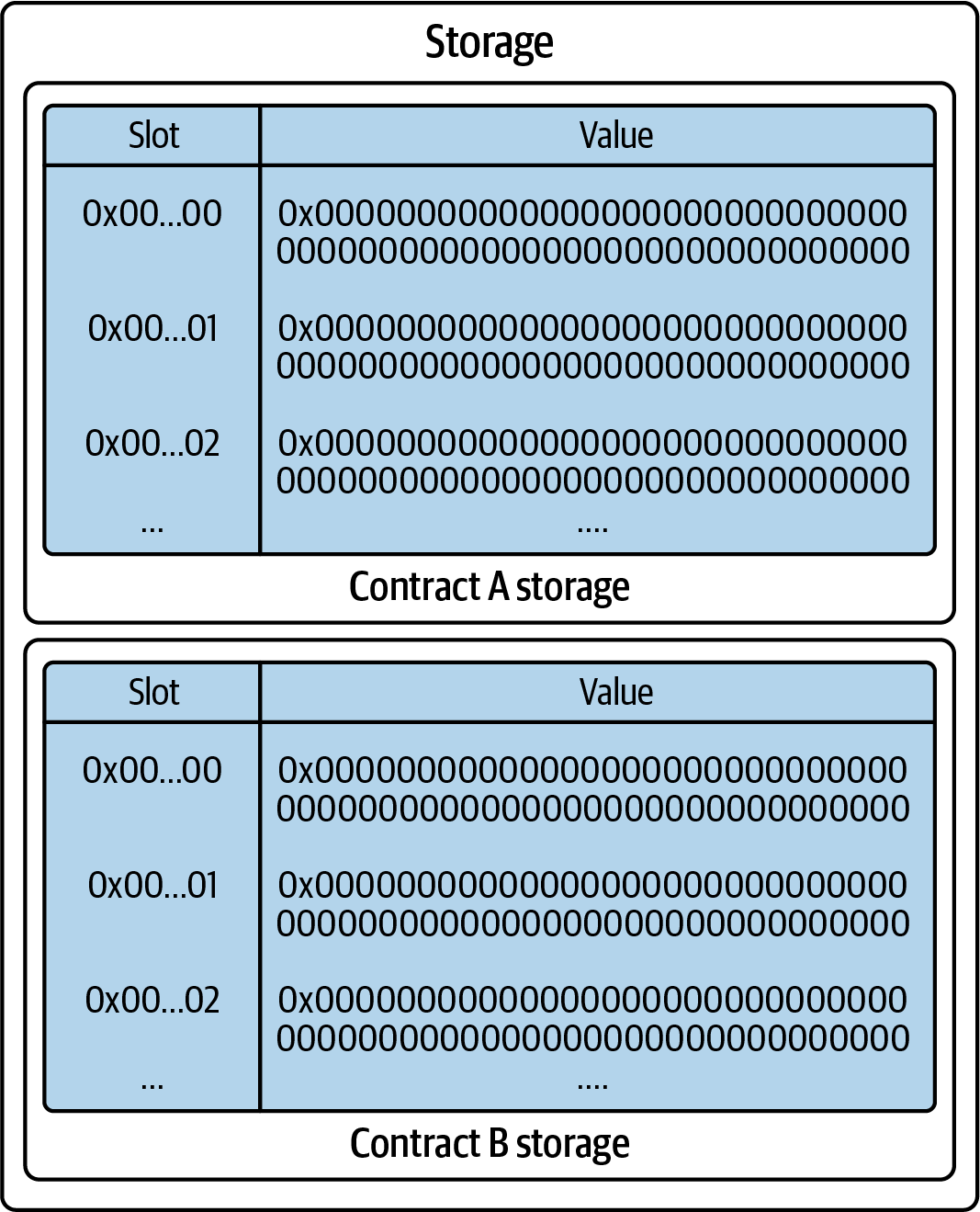

Data structures

Ethereum’s state is stored locally on each node as a database (usually Google’s LevelDB), which contains the transactions and system state in a serialized hashed data structure called a Merkle-Patricia trie.

Consensus algorithm

Ethereum transitioned from a PoW to a PoS consensus mechanism to enhance energy efficiency and scalability. In PoS, validators stake their cryptocurrency to earn the right to validate transactions, create new blocks, and maintain network security. Ethereum’s PoS is the fusion of two distinct algorithms: Casper the Friendly Finality Gadget (FFG) and GHOST (Greedy Heaviest Observed Subtree) with latest message driven (LMD) updates (more on this in Chapter 15).

Economic security

Ethereum uses a PoS algorithm called Gasper that provides economic security to the blockchain. We’ll explore how Gasper works in detail in Chapter 15, including its role in finality and validator coordination.

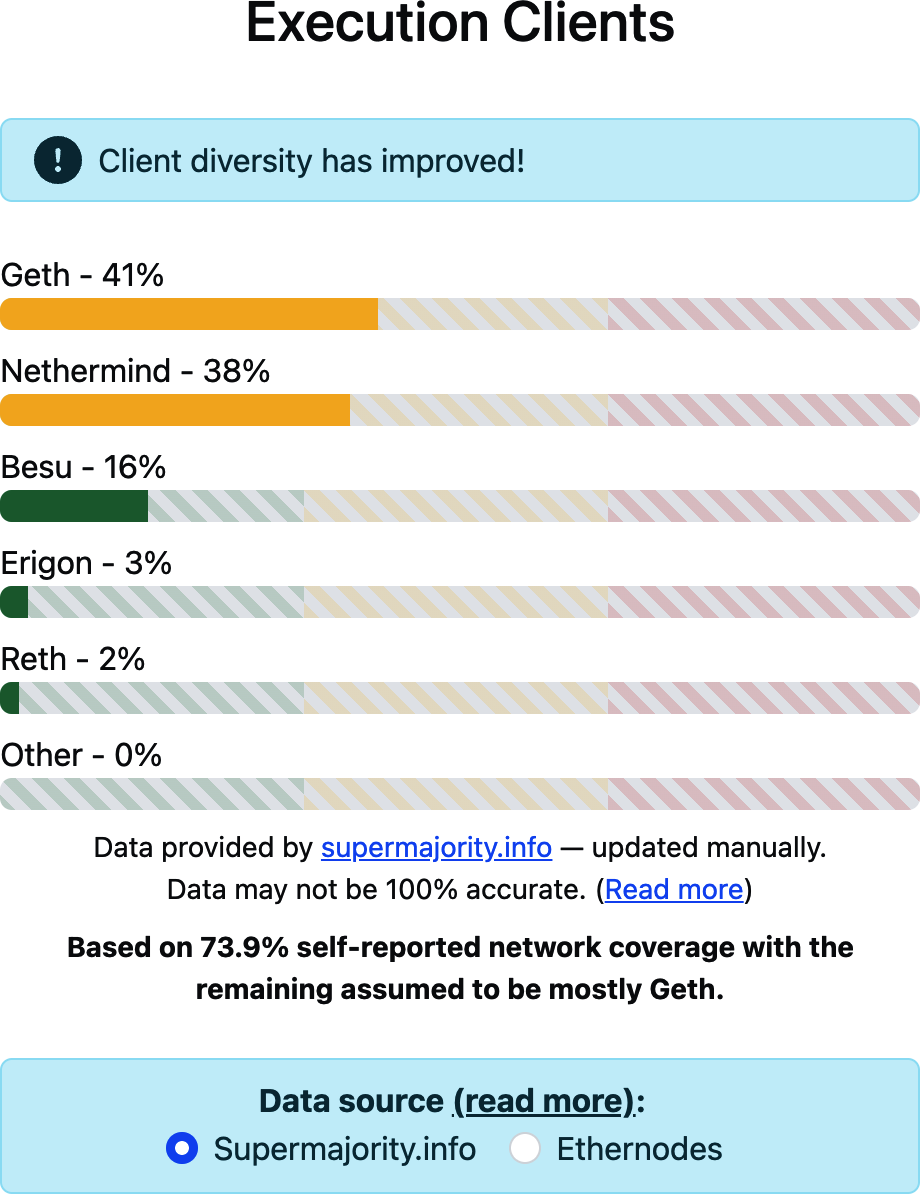

Clients

Ethereum has several interoperable implementations of its execution and consensus client software, the most prominent of which are go-ethereum (Geth) and Nethermind for execution and Prysm and Lighthouse for consensus.

These references provide additional information on the technologies mentioned here:

- Ethereum “Yellow Paper”

- Consensus client Python specifications

- Execution client Python specifications

Ethereum and Turing Completeness

As soon as you start reading about Ethereum, you will encounter the term Turing complete. Ethereum, they say, is Turing complete, unlike Bitcoin. What exactly does that mean?

The term refers to English mathematician Alan Turing, who is considered the father of computer science. In 1936, he created a mathematical model of a computer consisting of a state machine that manipulates symbols by reading and writing them on sequential memory (resembling an infinite-length paper tape). With this construct, Turing went on to provide a mathematical foundation to answer (in the negative) questions about universal computability, meaning whether all problems are solvable. He proved that there are classes of problems that are uncomputable. Specifically, he proved that the halting problem (whether it is possible, given an arbitrary program and its input, to determine whether the program will eventually stop running) is not solvable.

Turing further defined a system to be Turing complete if it can be used to simulate any Turing machine. Such a system is called a universal Turing machine (UTM).

Ethereum’s ability to execute a stored program—in a state machine called the EVM—while reading and writing data to memory makes it a Turing-complete system and therefore a UTM. Ethereum can compute any algorithm that can be computed by any Turing machine, given the limitations of finite memory.

Ethereum’s groundbreaking innovation is to combine the general-purpose computing architecture of a stored-program computer with a decentralized blockchain, thereby creating a distributed single-state (singleton) world computer. Ethereum programs run “everywhere” yet produce a common state that is secured by the rules of consensus.

Turing Completeness as a “Feature”

Hearing that Ethereum is Turing complete, you might arrive at the conclusion that this is a feature that is somehow lacking in a system that is Turing incomplete. Rather, it is the opposite. Turing completeness is very easy to achieve; in fact, the simplest Turing-complete state machine known has four states and uses six symbols, with a state definition that is only 22 instructions long. Indeed, sometimes systems are found to be “accidentally Turing complete” (here’s a fun reference of such systems).

However, Turing completeness is very dangerous, particularly in open-access systems like public blockchains, because of the halting problem described in the previous section. For example, modern printers are Turing complete and can be given files to print that send them into a frozen state. The fact that Ethereum is Turing complete means that any program of any complexity can be computed by Ethereum. But that flexibility brings some thorny security and resource management problems. An unresponsive printer can be turned off and turned back on again. That is not possible with a public blockchain.

Implications of Turing Completeness

Turing proved that you cannot predict whether a program will terminate by simulating it on a computer. In simple terms, we cannot predict the path of a program without running it. Turing-complete systems can run in infinite loops, a term used (in oversimplification) to describe a program that does not terminate. It is trivial to create a program that runs a loop that never ends. But unintended never-ending loops can arise without warning due to complex interactions between the starting conditions and the code. In Ethereum, this poses a challenge: every participating node (client) must validate every transaction, running any smart contracts it calls. But as Turing proved, Ethereum can’t predict if a smart contract will terminate or how long it will run without actually running it (possibly running forever). Whether by accident or on purpose, a smart contract can be created such that it runs forever when a node attempts to validate it. This is effectively a denial-of-service (DoS) attack. And of course, between a program that takes a millisecond to validate and one that runs forever is an infinite range of nasty, resource-hogging, memory-bloating, CPU-overheating programs that simply waste resources. In a world computer, a program that abuses resources gets to abuse the world’s resources. How does Ethereum constrain the resources used by a smart contract if it cannot predict resource use in advance?

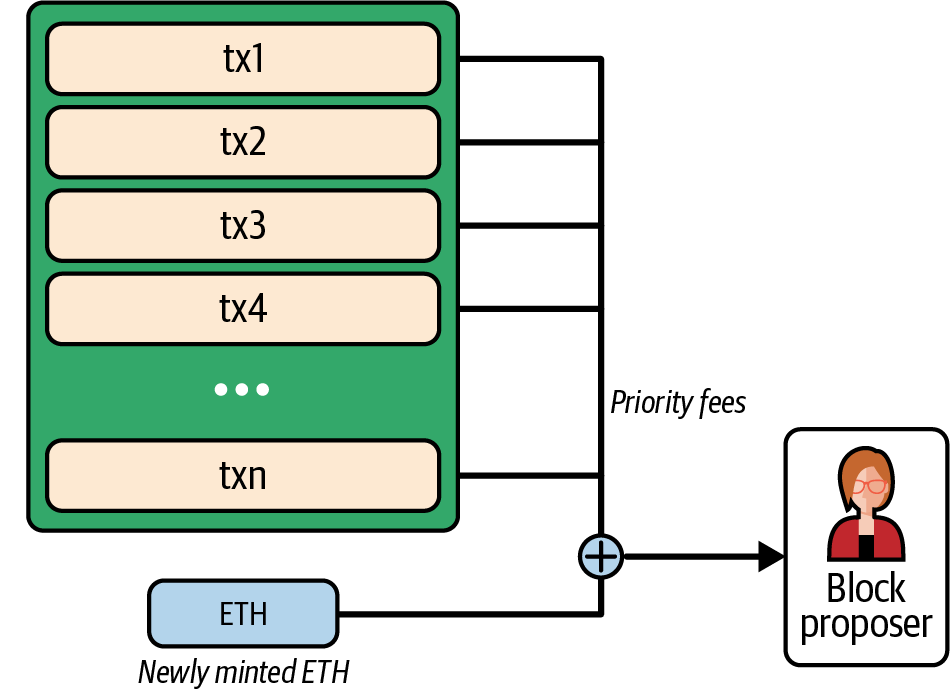

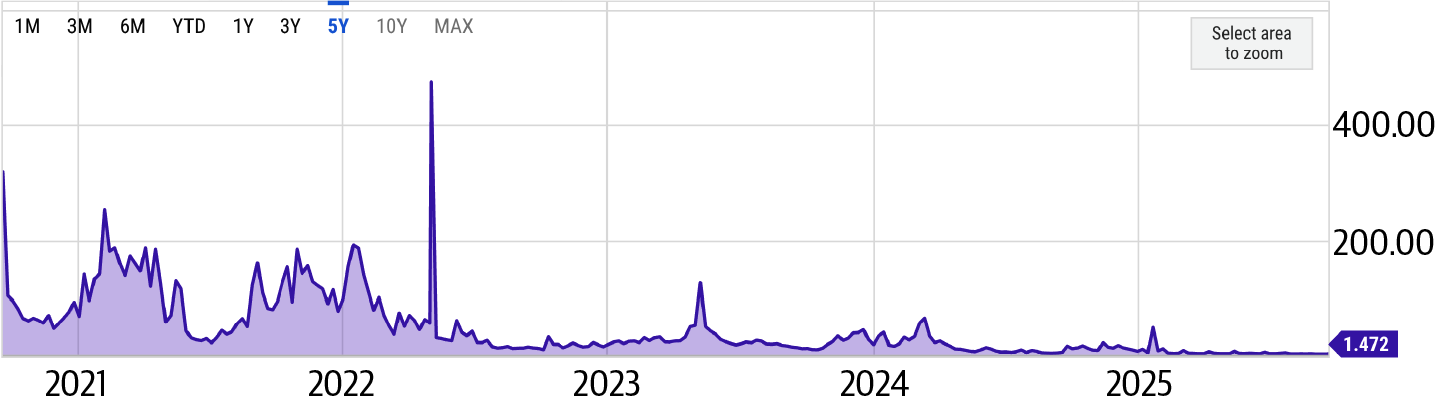

To answer this challenge, Ethereum introduced a metering mechanism called gas. As the EVM executes a smart contract, it carefully accounts for every instruction (computation, data access, etc.). Each instruction has a predetermined cost in units of gas. When a transaction triggers the execution of a smart contract, it must include an amount of gas that sets the upper limit of what can be consumed running the smart contract. The EVM will terminate execution if the amount of gas consumed by computation exceeds the gas available in the transaction. Gas is the mechanism Ethereum uses to allow Turing-complete computation while limiting the resources that any program can consume.

The next question is: how does one get gas to pay for computation on the Ethereum world computer? You won’t find gas on any exchanges. It can only be purchased as part of a transaction and can only be bought with ether. Ether needs to be sent along with a transaction, and it needs to be explicitly earmarked for the purchase of gas, along with an acceptable gas price. Just like at the pump, the price of gas is not fixed. Gas is purchased for the transaction, the computation is executed, and any unused gas is refunded back to the sender of the transaction.

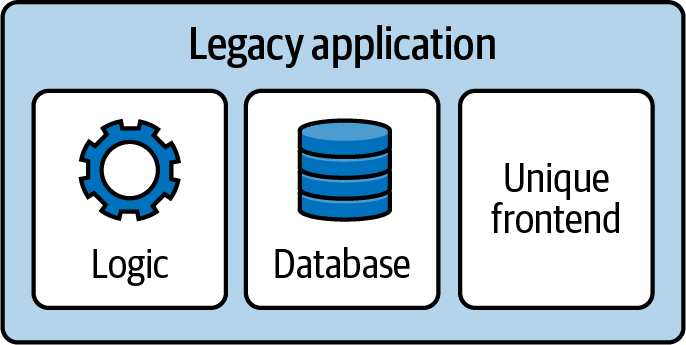

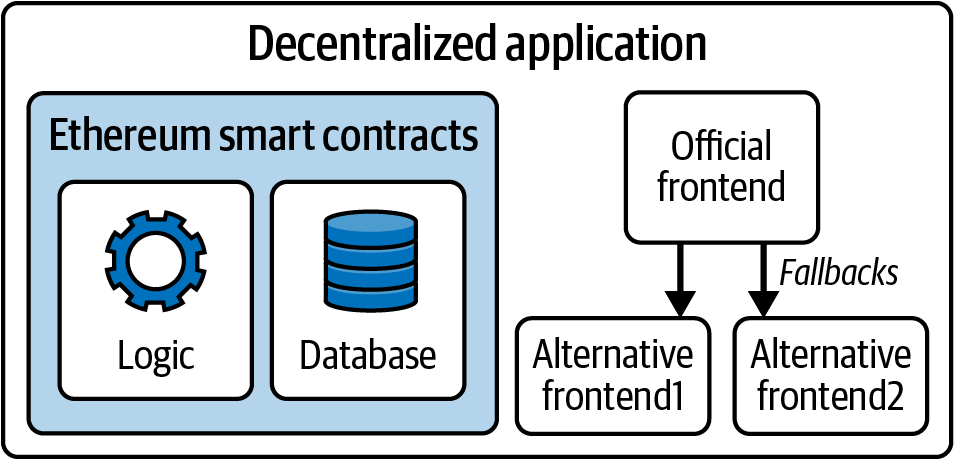

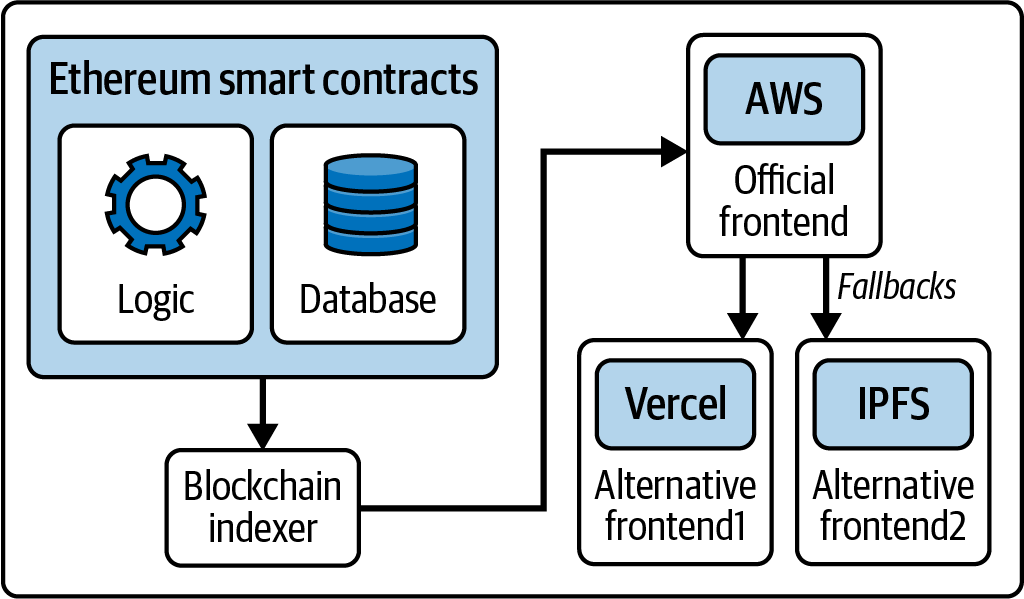

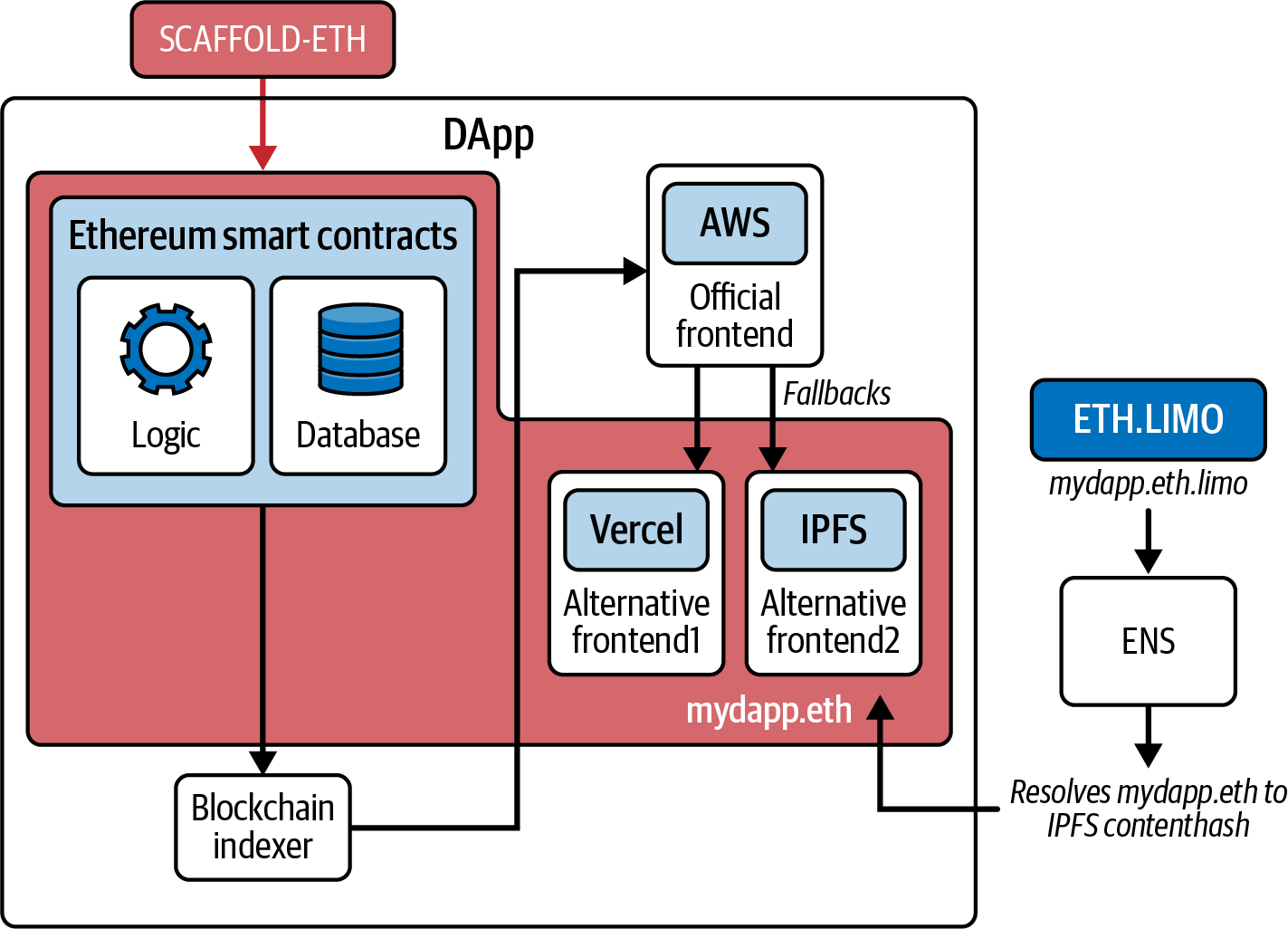

From General-Purpose Blockchains to DApps

Ethereum started as a way to make a general-purpose blockchain that could be programmed for a variety of uses. But very quickly, Ethereum’s vision expanded to become a platform for programming DApps. DApps represent a broader perspective than smart contracts. A DApp is, at the very least, a smart contract and a web user interface. More broadly, a DApp is a web application that is built on top of open, decentralized, P2P infrastructure services.

A DApp is composed of at least:

- Smart contracts on a blockchain

- A web frontend user interface

In addition, many DApps include other decentralized components, such as:

- A decentralized (P2P) storage protocol and platform

- A decentralized (P2P) messaging protocol and platform

From a practical perspective, the Ethereum web3.js JavaScript library bridges JavaScript applications that run in your browser with the Ethereum blockchain. It originally included a P2P storage network called Swarm and a P2P messaging service called Whisper—tools that made it possible to develop fully decentralized Web3 DApps. Despite the appeal of this fully decentralized DApp design, it did not gain much traction in the years following. Compromises had to be accepted to improve the user experience and boost user adoption, and a centralized Web2 website interacting with smart contracts is nowadays the standard for a DApp.

The Third Age of the Internet

In 2004, the term Web 2.0 came to prominence as a label of the evolution of the web toward user-generated content, responsive interfaces, and interactivity. Web 2.0 is not a technical specification but rather a term describing the new focus of web applications.

The concept of DApps is meant to take the Web to its next natural evolutionary stage, introducing decentralization with P2P protocols into every aspect of a web application. The term used to describe this evolution is Web3, meaning the third “version” of the web. First proposed by Gavin Wood, Web3 represents a new vision and focus for web applications: from centrally owned and managed applications to applications built on decentralized protocols.

Ethereum’s Development Culture

So far, we’ve talked about how Ethereum’s goals and technology differ from those of other blockchains that preceded it, like Bitcoin. Ethereum also has a very different development culture.

In Bitcoin, development is guided by conservative principles: all changes are carefully studied to ensure that none of the existing systems are disrupted. For the most part, changes are only implemented if they are backward compatible. Existing clients are allowed to opt in but will continue to operate if they decide not to upgrade. This cautious approach aligns with Bitcoin’s governance model, where changes go through the Bitcoin Improvement Proposal (BIP) process, an intentionally slow and consensus-driven pipeline designed to preserve stability.

In Ethereum, by comparison, the community’s development culture is focused on the future rather than the past. The (not entirely serious) mantra is “move fast and break things.” If a change is needed, it is implemented, even if that means invalidating prior assumptions, breaking compatibility, or forcing clients to update. Ethereum’s governance reflects this more hands-on style, with coordination happening publicly through frequent AllCoreDevs calls where researchers, client teams, and ecosystem stakeholders discuss and align on upcoming changes. It’s a more agile and iterative process that trades some stability for a faster pace of innovation.

What this means to you as a developer is that you must remain flexible and be prepared to rebuild your infrastructure as some of the underlying assumptions change. One of the big challenges facing developers in Ethereum is the inherent contradiction between deploying code to an immutable system and a development platform that is still evolving. You can’t simply “upgrade” your smart contracts. You must be prepared to deploy new ones; migrate users, apps, and funds; and start over.

Ironically, this also means that the goal of building systems with more autonomy and less centralized control is still not fully realized. Autonomy and decentralization require a bit more stability in the platform than you’re likely to get in Ethereum in the next few years. To “evolve” the platform, you have to be ready to scrap and restart your smart contracts, which means you have to retain a certain degree of control over them.

But on the positive side, Ethereum is moving forward very quickly. There is little opportunity for bike-shedding: an expression that means holding up development by arguing over minor details, such as how to build the bicycle shed at the back of a nuclear power station. If you start bike-shedding, you might suddenly discover that while you were distracted, the rest of the development team changed the plan and ditched bicycles in favor of autonomous hovercraft.

Eventually, the development of the Ethereum platform will slow, and its interfaces will become fixed. But in the meantime, innovation is the driving principle. You’d better keep up because no one will slow down for you.

Why Learn Ethereum?

Blockchains have a very steep learning curve because they combine multiple disciplines into one domain: programming, information security, cryptography, economics, distributed systems, P2P networks, and so on. Ethereum makes this learning curve a lot less steep, so you can get started quickly. But just below the surface of a deceptively simple environment lies a lot more. As you learn and start looking deeper, there’s always another layer of complexity and wonder.

Ethereum is a great platform for learning about blockchains, and it’s building a massive community of developers, faster than any other blockchain platform. More than any other, Ethereum is a developer’s blockchain: built by developers for developers. A developer familiar with JavaScript applications can drop into Ethereum and start producing working code very quickly. For the first few years of Ethereum’s life, it was common to see T-shirts announcing that you can create a token in just five lines of code. Of course, this is a double-edged sword. It’s easy to write code, but it’s very hard to write good and secure code.

Many blockchain projects, like L2s, are based on Ethereum. Learning Ethereum helps you understand these projects better and gives you the tools to explore further developments in the blockchain world. This knowledge is key for anyone looking to get involved with the latest in blockchain technology.

Conclusion

Ethereum stands out as a groundbreaking platform in the blockchain landscape. Its design as a Turing-complete system allows for the creation of decentralized applications with sophisticated, programmable logic, going beyond the simpler functionality of Bitcoin.

For developers and technologists, understanding Ethereum opens doors to a deeper comprehension of blockchain technology and its potential applications. By mastering Ethereum, you gain the tools to participate in and contribute to the ongoing evolution of the internet, putting yourself at the cutting edge of this exciting field.

Chapter 2. Ethereum Basics

In this chapter, we will start exploring Ethereum. We'll discuss how to use wallets, create transactions, and run a basic smart contract.

Ether Currency Units

Ethereum's currency unit is called ether, identified also as ETH or with the symbols Ξ (from the Greek letter Xi that looks like a stylized capital E) or, less often, ♦: for example, 1 ether, 1 ETH, Ξ1, or ♦1.

Tip

Use Unicode characters U+039E for Ξ and U+2666 for ♦.

Ether is subdivided into smaller units, down to the smallest unit possible, which is named wei. One ether is 1 quintillion wei (1 × 10^18^, or 1,000,000,000,000,000,000). You may hear people refer to the currency as "Ethereum," too, but this is a common beginner's mistake. Ethereum is the system; ether is the currency.

The value of ether is always represented internally in Ethereum as an unsigned integer value denominated in wei. When you transact 1 ether, the transaction encodes 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 wei as the value.

Ether's various denominations have both a scientific name using the International System of Units (SI) and a colloquial name that pays homage to many of the great minds of computing and cryptography. Table 2-1 lists the various units, their colloquial (common) names, and their SI names. In keeping with the internal representation of value, the table shows all denominations in wei (first row), with ether shown as 10^18^ wei in the seventh row.

Table 2-1. Ether denominations and unit names

| Value (in wei) | Exponent | Common name | SI name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Wei | Wei |

| 1,000 | 10^3^ | Babbage | Kilowei or femtoether |

| 1,000,000 | 10^6^ | Lovelace | Megawei or picoether |

| 1,000,000,000 | 10^9^ | Shannon | Gigawei or nanoether |

| 1,000,000,000,000 | 10^12^ | Szabo | Microether or micro |

| 1,000,000,000,000,000 | 10^15^ | Finney | Milliether or milli |

| 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 | 10^18^ | Ether | Ether |

| 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 | 10^21^ | Grand | Kiloether |

| 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 | 10^24^ | Megaether |

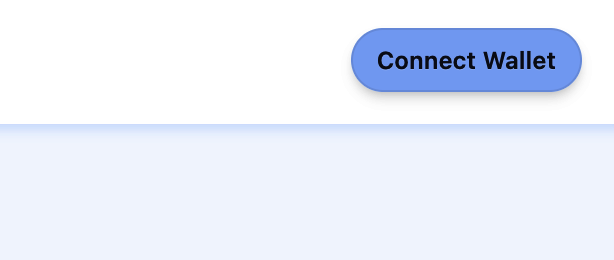

Choosing an Ethereum Wallet

The term wallet has come to mean many things, although the definitions are all related, and on a day-to-day basis, they all boil down to pretty much the same thing. We will use the term wallet to refer to a software application that helps you manage your Ethereum account. In short, an Ethereum wallet is your gateway to the Ethereum system. It holds your keys and can create and broadcast transactions on your behalf. Choosing an Ethereum wallet can be difficult because there are many options with different features and designs. Some are more suitable for beginners, and some are more suitable for experts. The Ethereum platform itself is still being improved, and the "best" wallets are often the ones that adapt to the changes that come with the platform upgrades.

But don't worry! If you choose a wallet and don't like how it works—or if you like it at first but later want to try something else—you can change wallets quite easily. All you have to do is make a transaction that sends your funds from the old wallet to the new wallet or export your private keys and import them into the new one.

Remember that for a wallet application to work, it must have access to your private keys, so it is vital that you only download and use wallet applications from sources you trust. Fortunately, in general, the more popular a wallet application is, the more trustworthy it is likely to be. Nevertheless, it is good practice to avoid "putting all your eggs in one basket" and have your Ethereum accounts spread across a couple of wallets and seed phrases.

The following are some good starter wallets; the selection of these wallets is not an endorsement of their quality or security. They are simply a good starting place for demonstrations and testing. All of the following wallets are both browser-extension wallets and mobile wallets:

MetaMask

MetaMask is easy to use and convenient for testing as it is able to connect to a variety of Ethereum nodes and test blockchains.

Rabby Wallet

Rabby is often a good choice for new users as it is designed for simplicity and ease of use. It has a lot of security features built in.

Phantom

Phantom is a wallet that can connect only to Ethereum, among other non-EVM chains.

Control and Responsibility

Open blockchains like Ethereum are important because they operate as a decentralized system. That means lots of things, but one crucial aspect is that each user of Ethereum can—and should—control their own private keys, which control access to funds and smart contracts. We sometimes call the combination of access to funds and smart contracts an account or wallet. These terms can get quite complex in their functionality, so we will go into this in more detail later. As a fundamental principle, however, it is as easy as one private key equals one "account." Some users choose to give up control over their private keys by using a third-party custodian, such as an online centralized exchange. In this book, we will teach you how to take control and manage your own private keys.

With control comes a big responsibility. If you lose your private keys, you lose access to your funds and contracts. No one can help you regain access—your funds will be locked forever. Here are a few tips to help you manage this responsibility:

-

Do not improvise security. Use tried-and-tested standard approaches.

-

The more important the account (e.g., the higher the value of the funds controlled compared to your total net worth), the higher the security measures that should be taken.

-

One of the highest security levels is gained from a hardware wallet device, but this level is not required for every account.

-

Never store your private key in plain form, especially digitally. Fortunately, most user interfaces today won't even let you see the raw private key without throwing multiple warnings.

-

When you are prompted to back up a key as a mnemonic word sequence, use pen and paper to make a physical backup. Do not leave that task "for later"; you will forget. These backups can be used to rebuild your private key in case you lose all the data saved on your system or if you forget or lose your password. However, they can also be used by attackers to get your private keys, so never store them digitally and keep at least one physical copy stored securely.

-

Before transferring any large amounts (especially to new addresses), first do a small test transaction (e.g., less than $1 value) and wait for confirmation of receipt.

-

When you create a new account, start by sending only a small test transaction to the new address. Once you receive the test transaction, try sending it back again from that account. There are lots of reasons account creation can go wrong, and if it has gone wrong, it is better to find out with a small loss. If the tests work, all is well (also a testnet could be used to avoid any kind of loss).

-

Public block explorers are an easy way to independently see whether a transaction has been accepted by the network; while this information is already public on the blockchain, block explorers make it incredibly easy to access. However, this convenience has a negative impact on your privacy because you reveal your addresses to block explorers, which can track you.

-

Public block explorers are usually reliable, but not all the time—do not trust them blindly.

-

Do not send money to any of the addresses shown in this book. The private keys are listed in the book, and someone could immediately take that money.

Now that we've covered some basic best practices for key management and security, let's get to work using MetaMask!

Getting Started with MetaMask

Open the Google Chrome browser and navigate to Extensions. Search for "MetaMask" and click on the logo of a fox. You should see something similar to Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1. The detail page of the MetaMask Chrome extension

It's important to verify that you are downloading the real MetaMask extension because sometimes people are able to sneak malicious extensions past Google's filters. The real one does the following:

-

Shows the ID

nkbihfbeogaeaoehlefnkodbefgpgknnin the address bar -

Is offered by https://metamask.io

-

Has more than 5,400 reviews

-

Has more than 15 million users

Once you confirm that you are looking at the correct extension, click "Add to Chrome" to install it.

Creating a Wallet

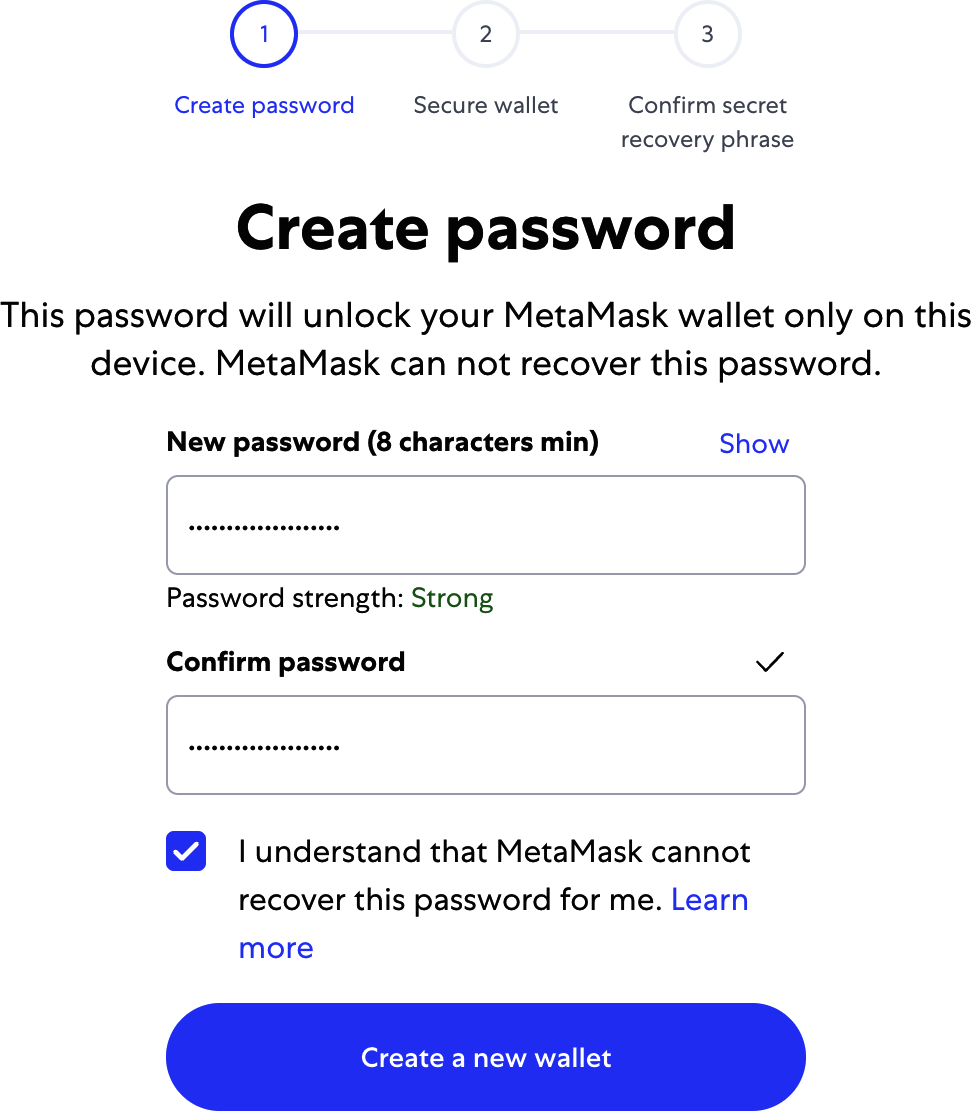

Once MetaMask is installed, you should see a new icon (the head of a fox) in your browser's toolbar. Click it to get started. You will be asked to accept the terms and conditions and then to create your new Ethereum wallet by entering a password (see Figure 2-2).

Figure 2-2. The password page of the MetaMask Chrome extension

Tip

The password controls access to MetaMask so that it can't be used by anyone with access to your browser. This password is only for your local device; if an attacker gains access to the private key or seed phrase, they will be able to access the funds in your addresses. The password is not needed if the attacker has the private key or seed phrase.

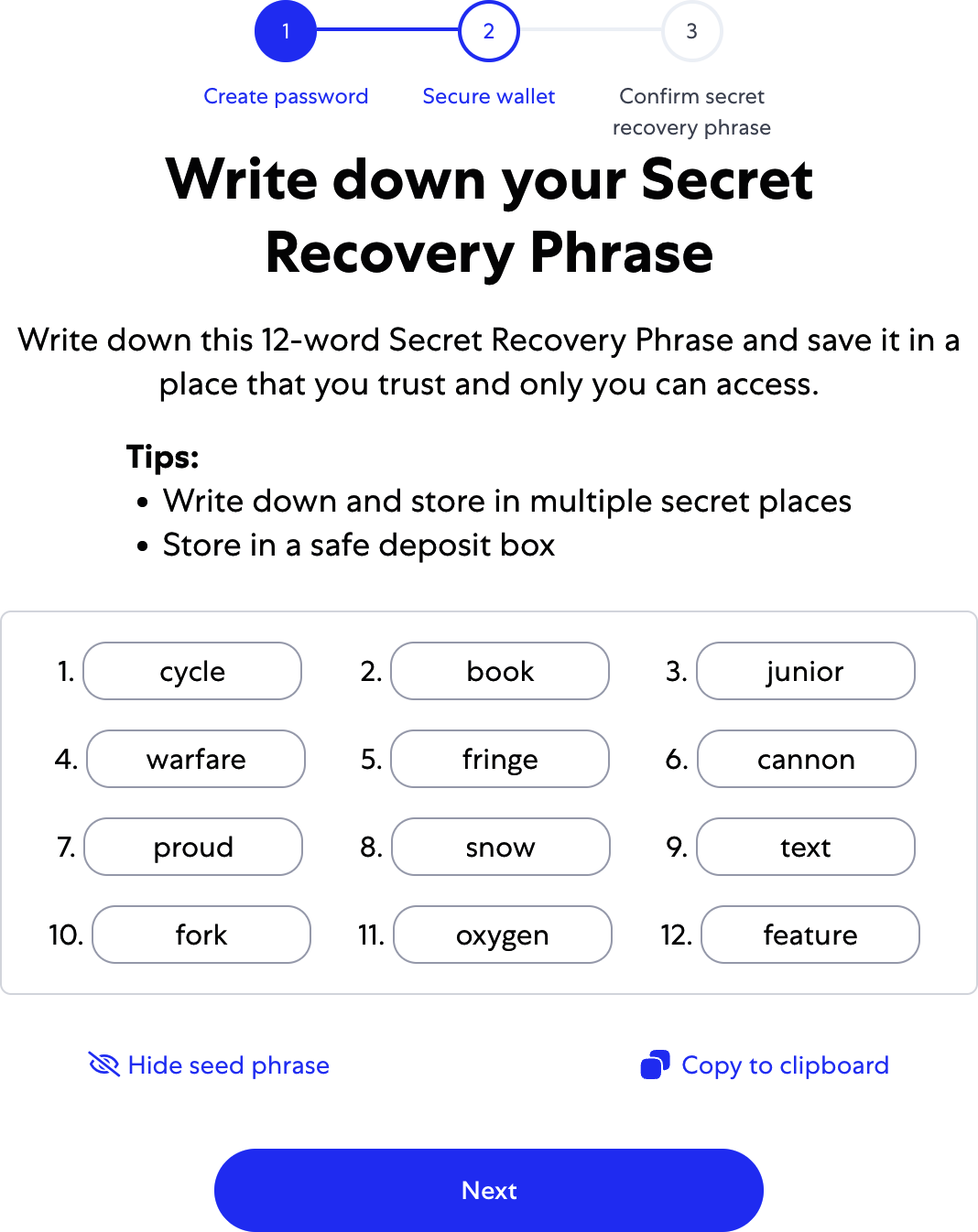

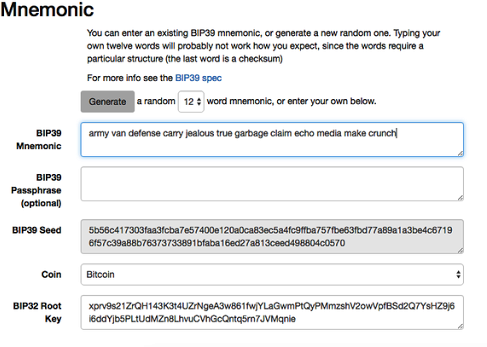

Once you've set a password, MetaMask will generate a wallet for you and show you a mnemonic backup consisting of 12 English words (see Figure 2-3). These words can be used in any compatible wallet to recover access to your funds should something happen to MetaMask or your computer. You do not need the password for this recovery; the 12 words are sufficient.

Figure 2-3. The mnemonic backup of your wallet created by MetaMask

Tip

Back up your mnemonic (12 words) on paper, twice. Store the two paper backups in two separate secure locations, such as a fire-resistant safe, a locked drawer, or a safe deposit box. Treat the paper backups like cash of equivalent value to what you store in your Ethereum wallet. Anyone with access to these words can gain access to and steal your money. We will go into much more detail on how to keep your seed phrase safe in Chapter 5.

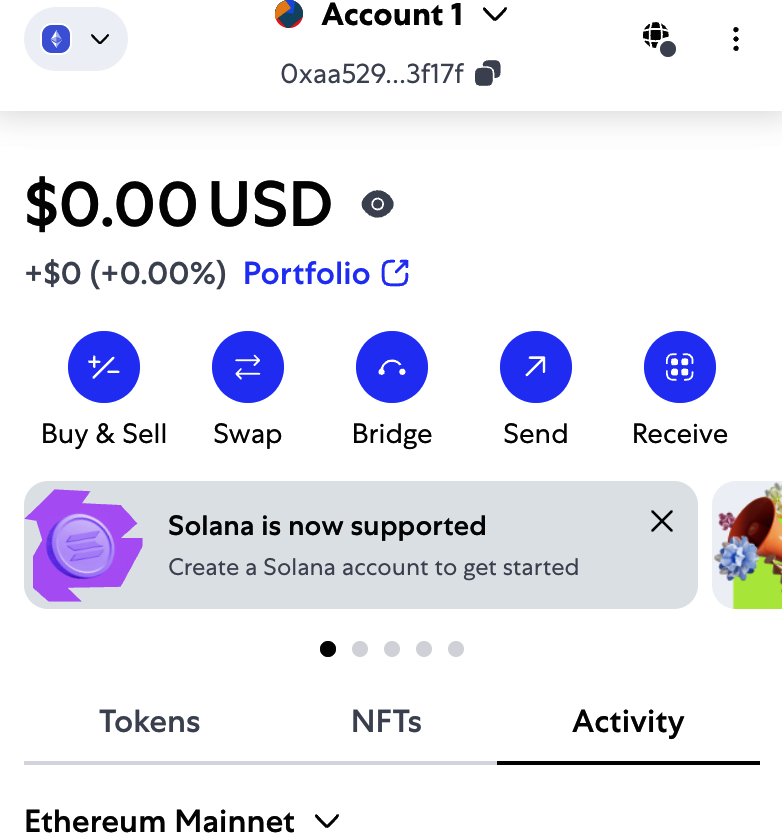

Once you have confirmed that you have stored the mnemonic securely, you'll be able to see the details of your Ethereum account, as shown in Figure 2-4.

Figure 2-4. Your Ethereum account in MetaMask

Note

Do not send any assets to the addresses shown in this book. The seed phrase is public for educational purposes, and every asset sent to these addresses will probably be lost.

Your account page shows the name of your account ("Account 1" by default), an Ethereum address (0xaa529…f17f in the example), and a colorful icon to help you visually distinguish this account from other accounts. At the top of the account page, you can see which Ethereum network you are currently working on ("Main Network" in the example).

Congratulations! You have set up your first Ethereum wallet.

Switching Networks

As you can see on the MetaMask account page, you can choose among multiple Ethereum networks. By default, MetaMask will try to connect to the main network. The other choices are public testnets, any Ethereum node of your choice, or nodes running private blockchains on your own computer (localhost):

Main Ethereum Network

The main public Ethereum blockchain. Real ETH, real value, and real consequences.

Sepolia Test Network

Launched in October 2021 as a proof-of-authority network by Ethereum's core developers, Sepolia has since transitioned to a PoS consensus, mirroring Ethereum's mainnet environment.

Holesky Test Network

The Holesky Testnet is Ethereum's advanced testing ground for staking, infrastructure, and protocol development.

Localhost 8545

Connects to a node running on the same computer as the browser. The node can be part of any public blockchain (main or testnet) or a private testnet.

Custom RPC

Allows you to connect MetaMask to any node with a Geth-compatible remote procedure call (RPC) interface. The node can be part of any public or private blockchain.

Note

Your MetaMask wallet uses the same private key and Ethereum address on all the networks it connects to. However, your Ethereum address balance on each Ethereum network will be different. For instance, if you use your keys to send ether on the Sepolia testnet, your balances on other networks will remain unaffected.

Getting Some Test Ether

Your first task is to get your wallet funded. You won't be doing that on the main network because real ether costs money and handling it requires a bit more experience. For now, you'll load your wallet with some testnet ether.

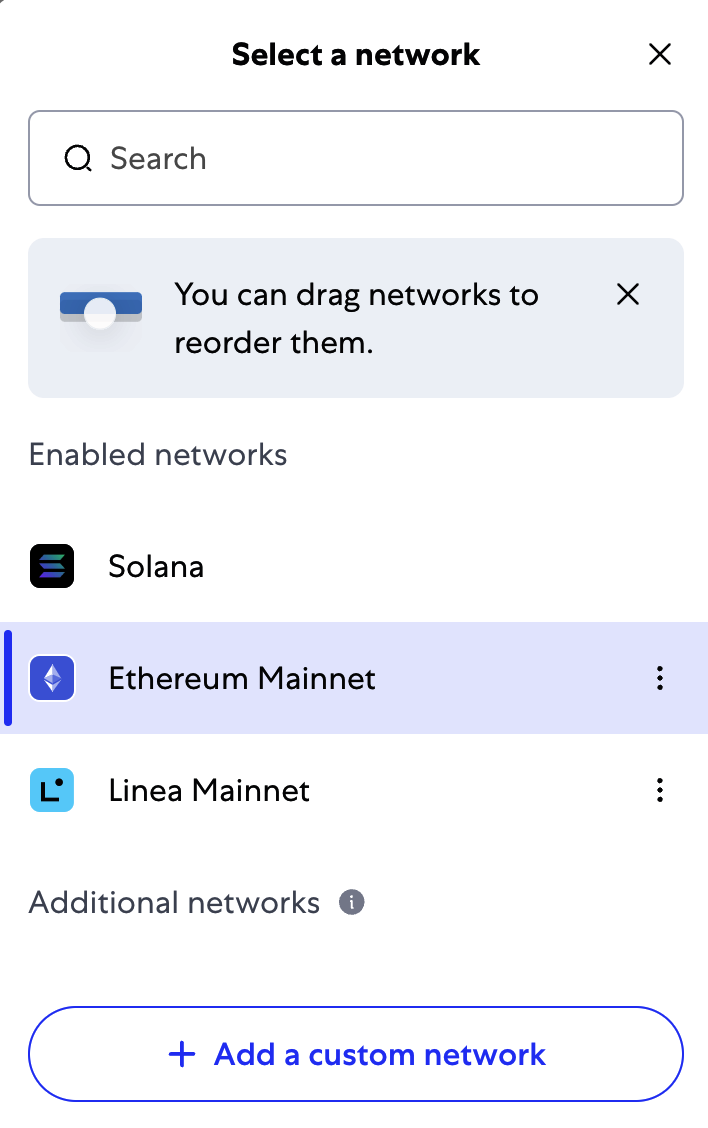

Switch MetaMask to the Sepolia Test Network by clicking the Ethereum icon on the top left; toggle the option "Show test networks" and click Sepolia, as shown in Figure 2-5.

Figure 2-5. MetaMask networks

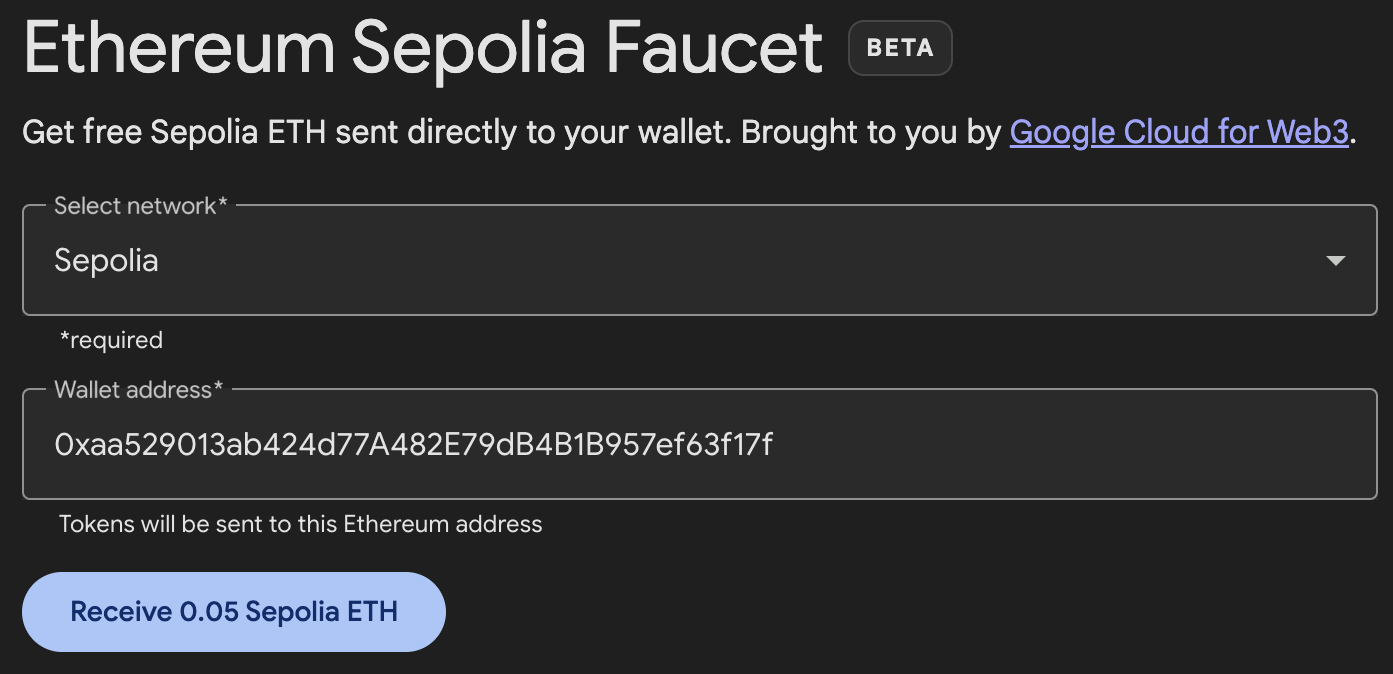

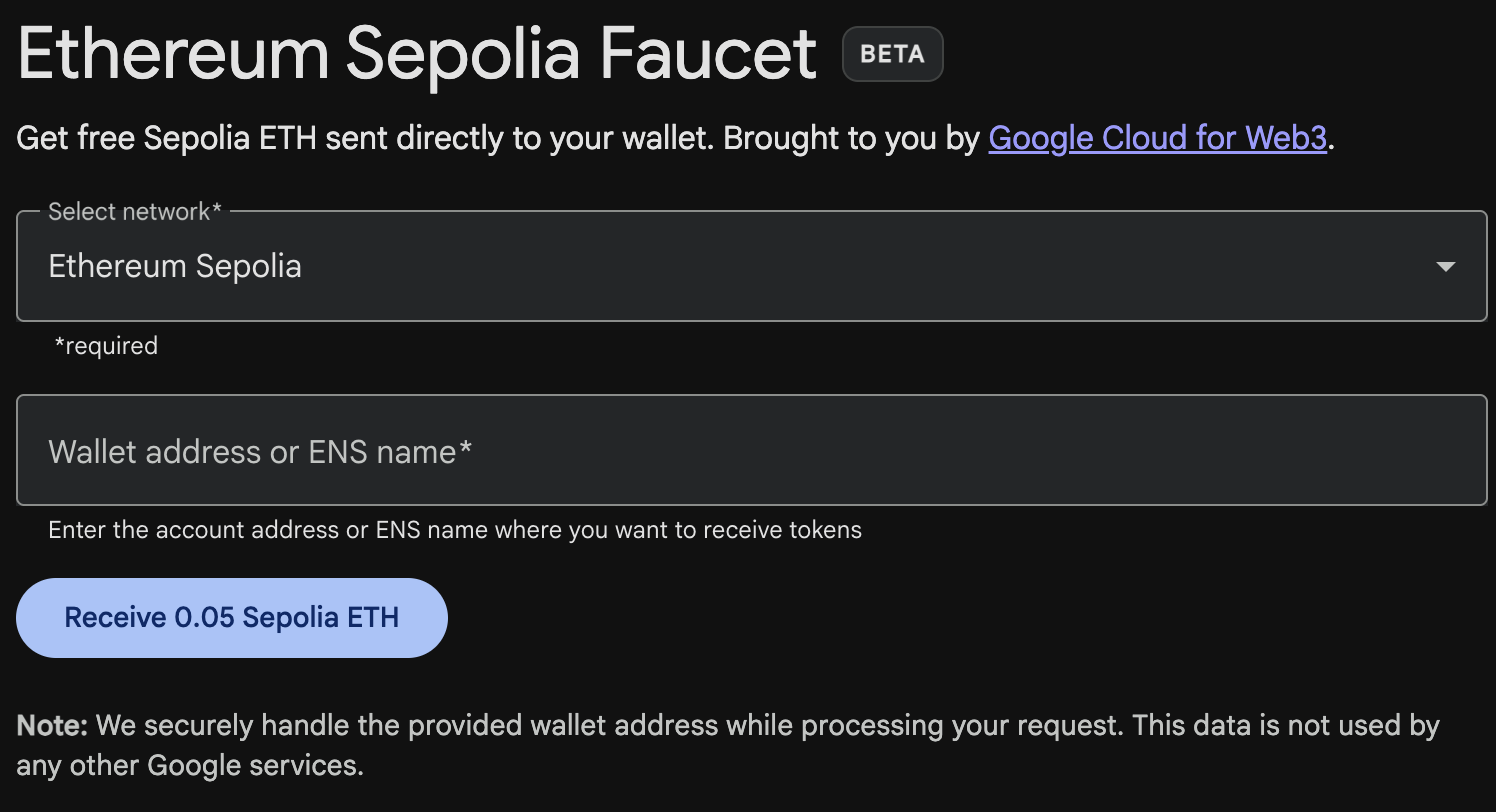

Click Buy, then navigate to one of the faucets in this list. Once you have decided which faucet you want to use—they are all pretty much equivalent—you can request ethers on the test network, as shown in Figure 2-6.

Figure 2-6. MetaMask Sepolia test faucet

The transaction ID for the request of testnet ether looks like this:

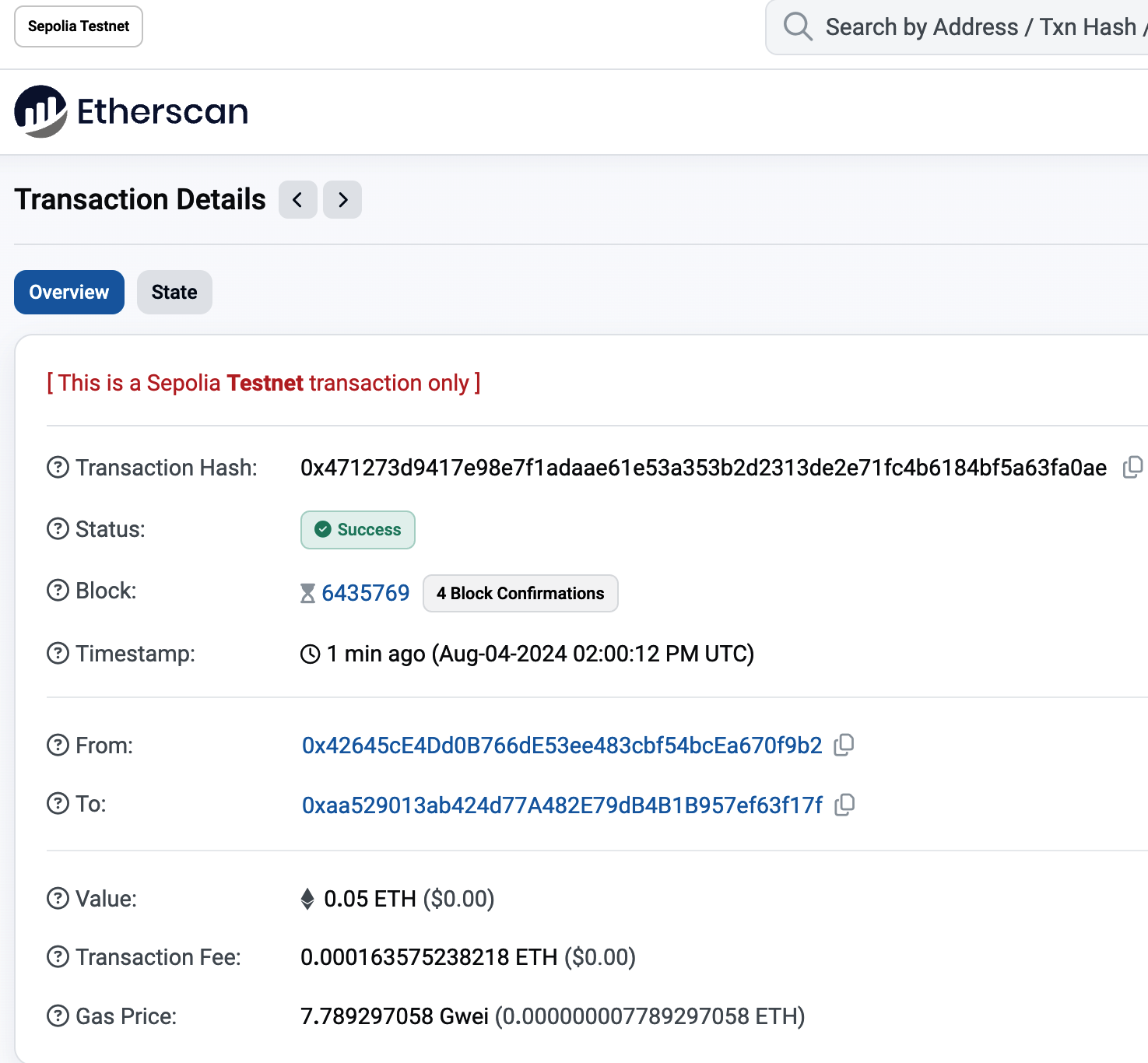

0x471273d9417e98e7f1adaae61e53a353b2d2313de2e71fc4b6184bf5a63fa0ae

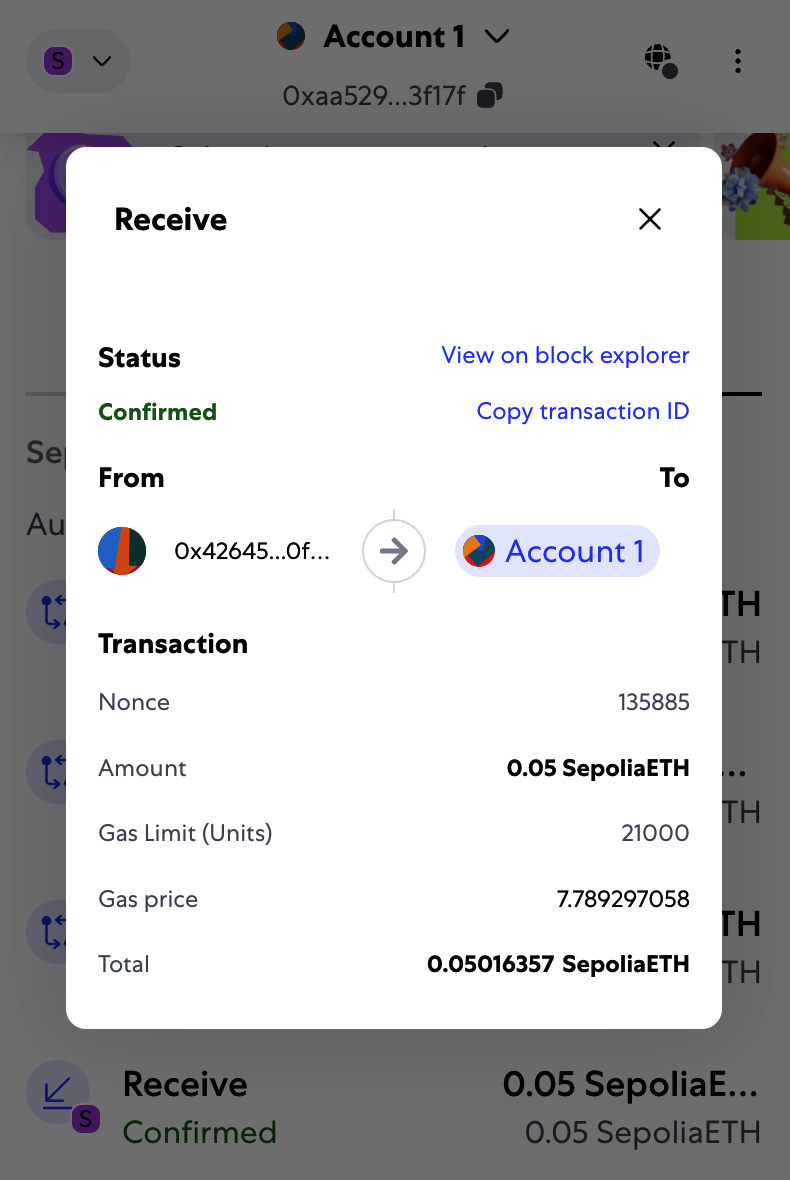

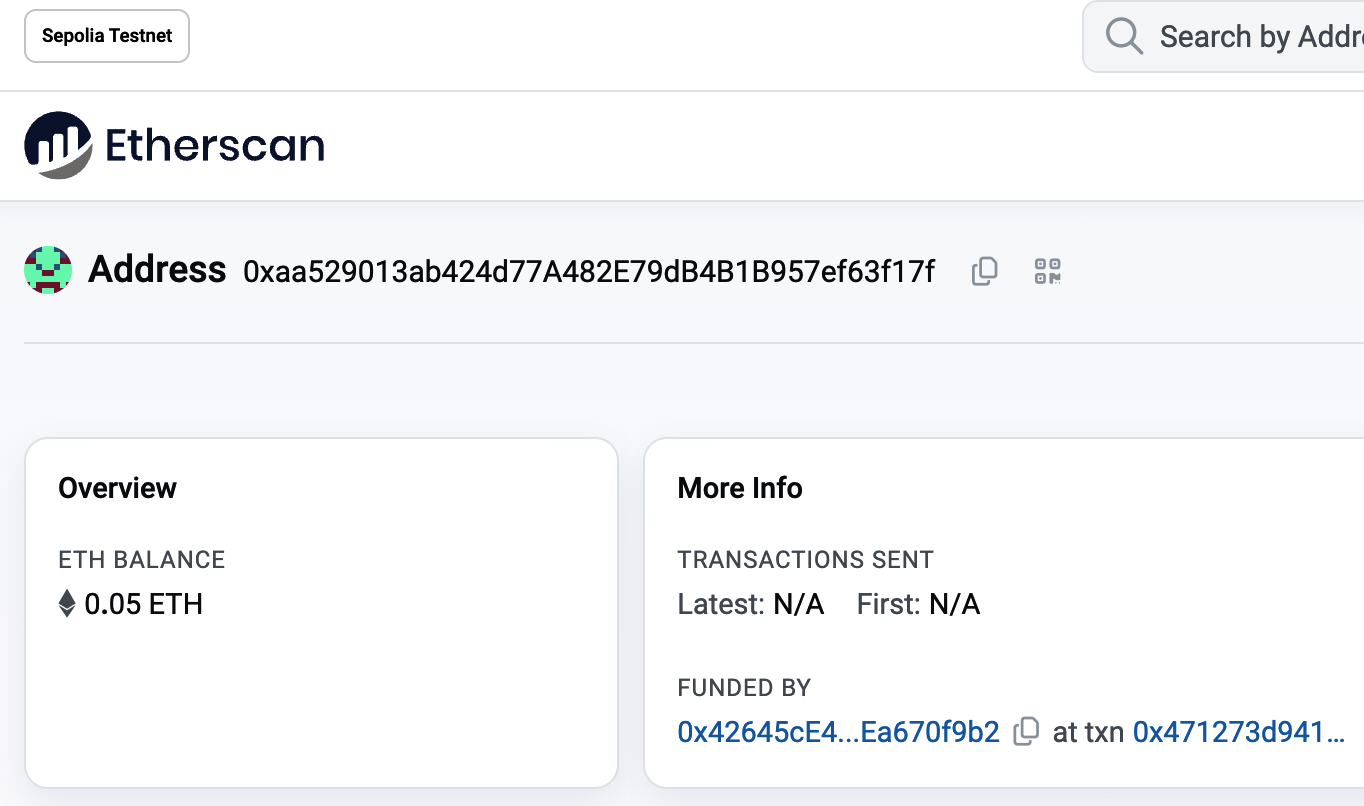

In a few seconds, the new transaction will be processed by the Sepolia network, and your MetaMask wallet will show a balance of 0.05 ETH (this depends on how much ether the faucet is willing to send). Now, click to the first transaction in your browser extension and click "View on block explorer," as shown in Figure 2-7. This will navigate to a block explorer, which is a website that allows you to visualize and explore blocks, addresses, and transactions.

Figure 2-7. Transaction viewed from MetaMask

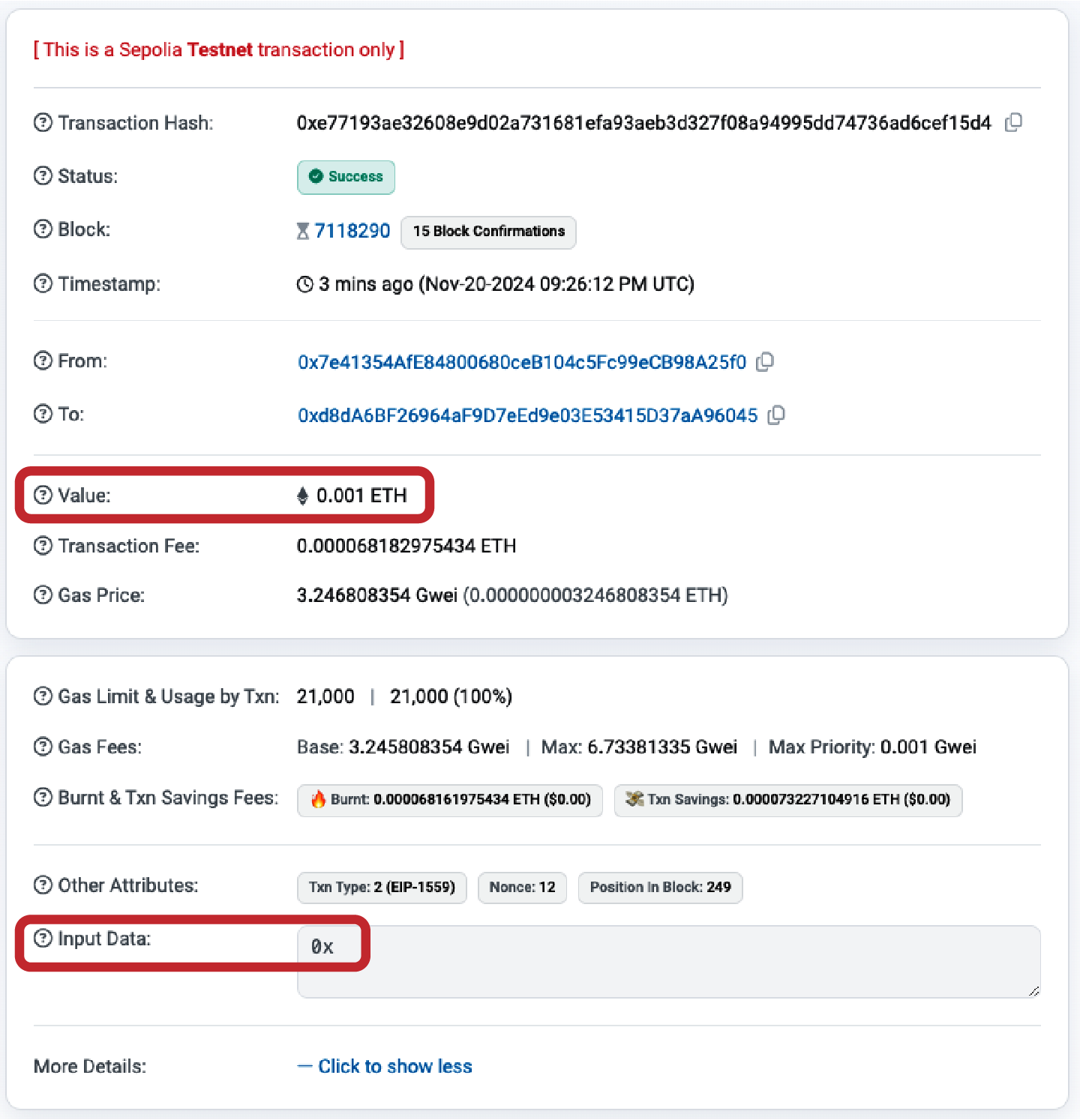

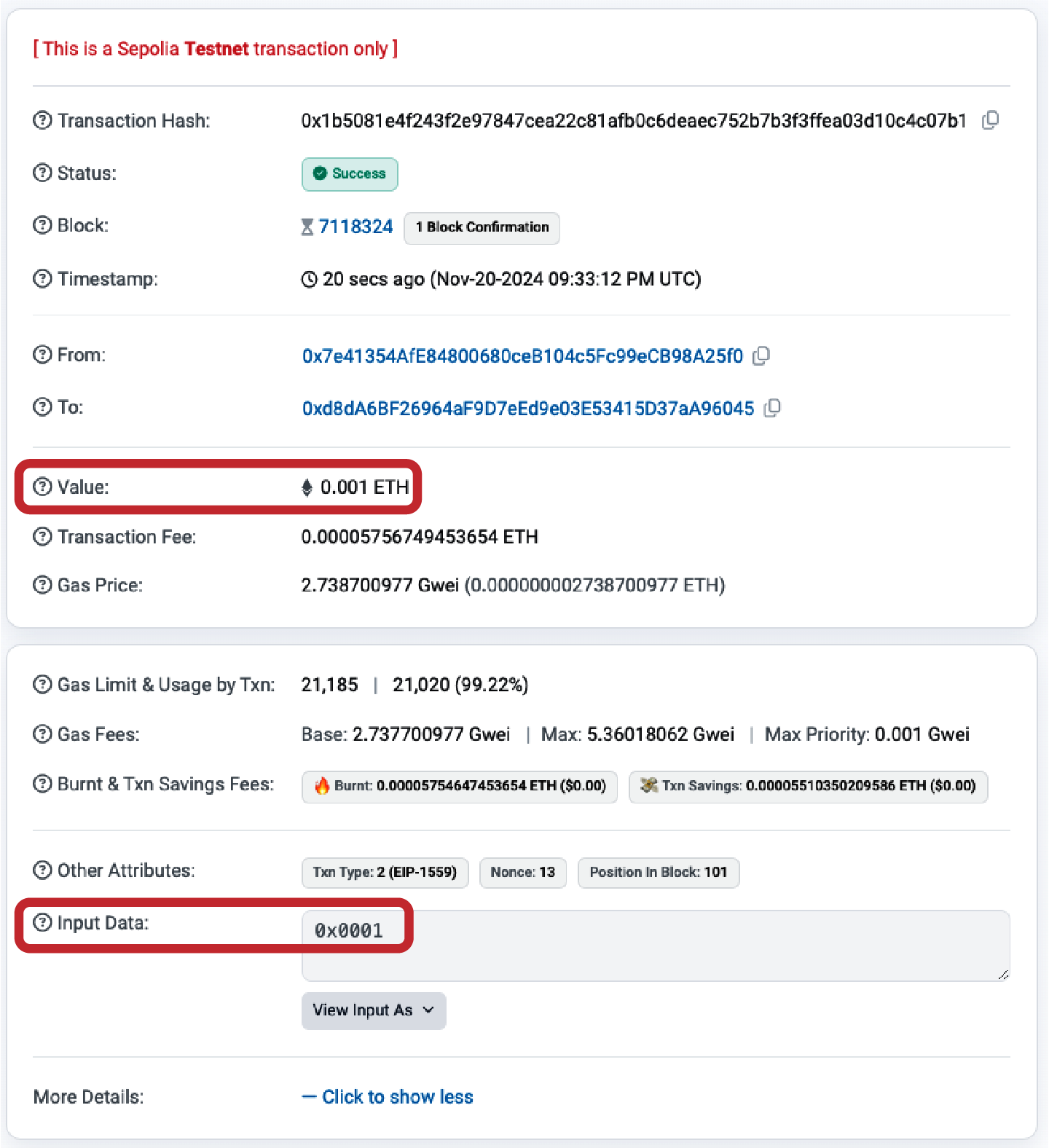

MetaMask uses the Etherscan block explorer, one of the more popular Ethereum block explorers. The transaction containing the payment from the Sepolia test faucet is shown in Figure 2-8.

Figure 2-8. Etherscan Sepolia block explorer

The transaction has been recorded on the Sepolia blockchain and can be viewed at any time by anyone, simply by searching for the transaction ID. Try entering the transaction hash into the sepolia.etherscan.io website to see it for yourself:

0x471273d9417e98e7f1adaae61e53a353b2d2313de2e71fc4b6184bf5a63fa0ae

Sending Ether from MetaMask

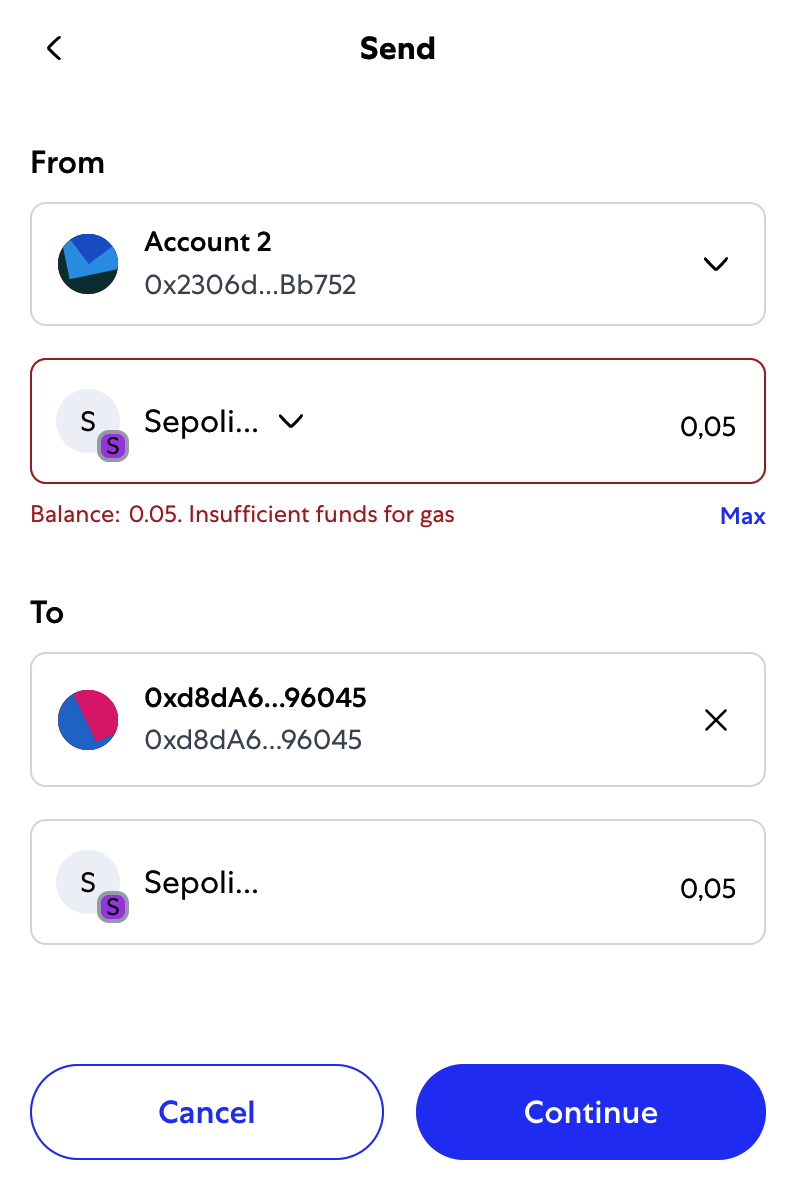

Once you've received your first test ether from the Sepolia test faucet, you can experiment with sending ether by trying to send some back to the faucet or to any other address. In this example, we will be trying to send some testnet ether to Vitalik Buterin, as shown in Figure 2-9.

Figure 2-9. Sending 0.05 ether to an address

Oops! You probably noticed that you can't complete the transaction—MetaMask says you have an insufficient balance. At first glance, this may seem confusing: you have 0.05 ETH, you want to send 0.05 ETH, so why is MetaMask saying you have insufficient funds?

The answer is because of the cost of gas. Every Ethereum transaction requires payment of a fee, which is collected by the network to validate the transaction. The fees in Ethereum are charged in a virtual currency called gas. You pay for the gas with ether, as part of the transaction.

Note

Fees are required on the test networks, too. Without fees, a test network would behave differently from the main network, making it an inadequate testing platform. Fees also protect the test networks from DoS attacks and poorly constructed contracts (e.g., infinite loops), much like they protect the main network.

When you send the transaction, MetaMask will calculate the average gas price of recent successful transactions—for example, at 3 gwei, which stands for gigawei. Wei is the smallest subdivision of the ether currency, as we discussed in "Ether Currency Units". The gas limit is set at the cost of sending a basic transaction: 21,000 gas units, which is the smallest amount of gas that can be used to send a transaction. Therefore, the maximum amount of ETH you will spend is 3 × 21,000 gwei = 63,000 gwei = 0.000063 ETH. (Be advised that average gas prices can fluctuate. We will see in a later chapter how you can increase or decrease your gas limit to ensure that your transaction takes precedence if need be.)

All this is to say that making a 0.05 ETH transaction costs 0.050063 ETH. Click Reject to cancel this transaction. Let's try again, this time by sending 0.01 ETH.

Exploring the Transaction History of an Address

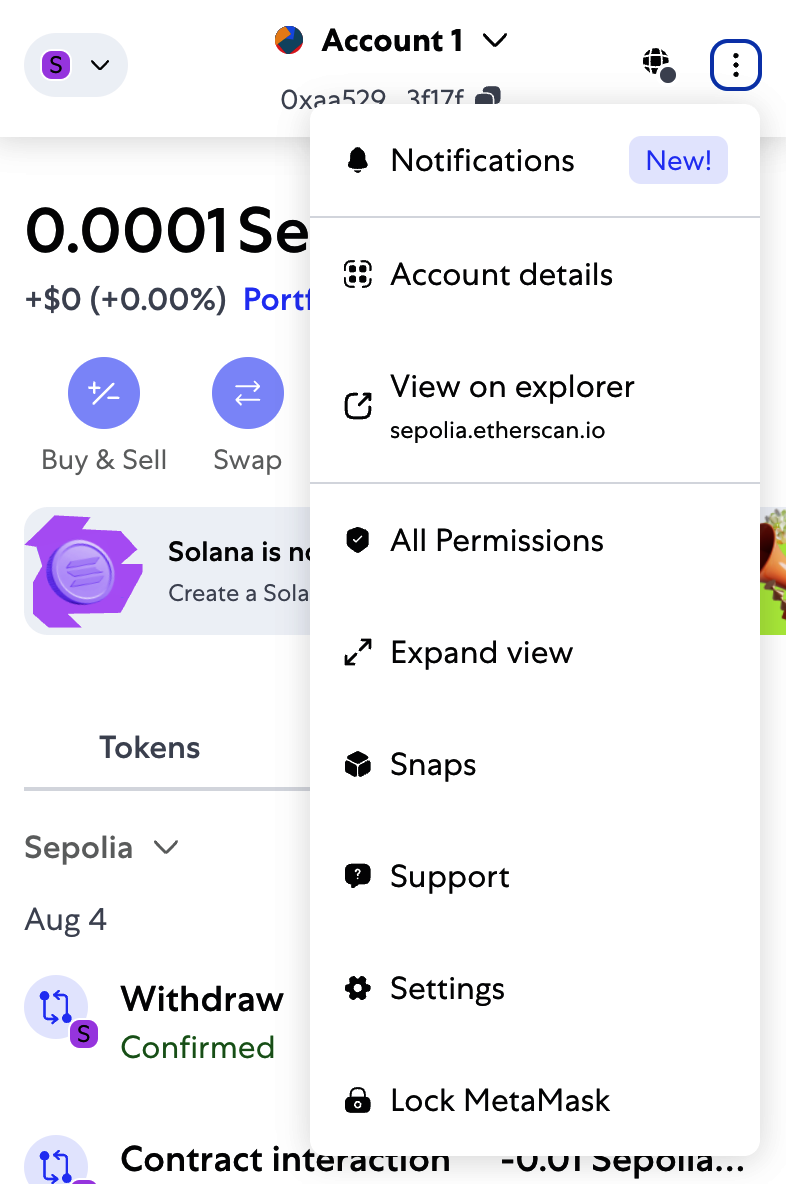

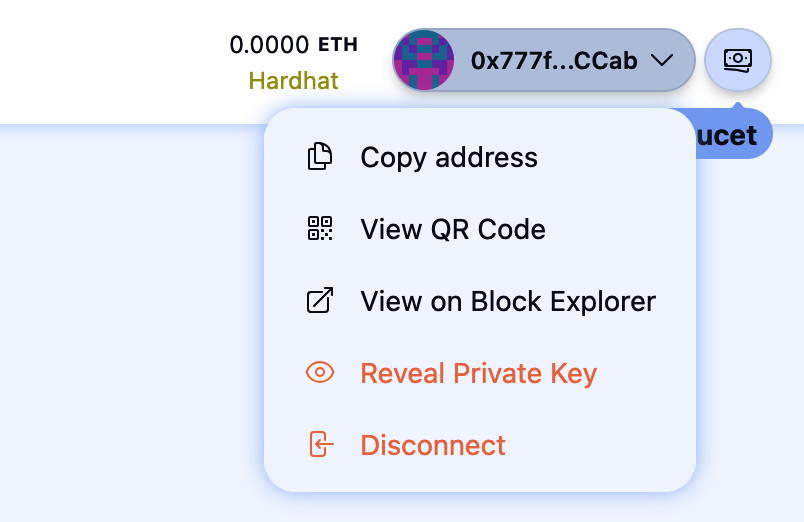

By now, you have become an expert in using MetaMask to send and receive test ether. Your wallet has received and sent payments. You can view all these transactions using the sepolia.etherscan.io block explorer. You can either copy your wallet address and paste it into the block explorer's search box or have MetaMask open the page for you. Next to your account icon in MetaMask, you will see a button showing three dots. Click it to show a menu of account-related options (see Figure 2-10).

Figure 2-10. MetaMask account context menu

Tip

The default settings of MetaMask are not very privacy centric. It is advisable to carefully analyze the settings found in Settings → Security and Privacy. Once you are familiar with how MetaMask works, it is also advisable to change the Ethereum mainnet network from the default one to one that uses an RPC with privacy settings that suit your needs. The most private solution would be to have your own node with an RPC to which you can connect; we will see how to do that in Chapter 3.

Select "View account on Etherscan" to open a web page in the block explorer showing your account's transaction history, as shown in Figure 2-11.

Figure 2-11. Address transaction history on Etherscan

Here you can see the entire transaction history of your Ethereum address. It shows all the transactions recorded on the Sepolia blockchain where your address is the sender or recipient. Click on a few of these transactions to see more details.

Warning

Beware, there is a known attack, called address poisoning, that can display transactions with spoofed addresses on the block explorer. The block explorer should be used for a quick check, but the information shown might not be accurate.

You can explore the transaction history of any address. Take a look at the transaction history of the Sepolia test faucet address (hint: it is the "sender" address listed in the oldest payment to your address). You can see all the test ether sent from the faucet to you and to other addresses. Every transaction you see can lead you to more addresses and more transactions. Before long, you will be lost in the maze of interconnected data. Public blockchains contain an enormous wealth of information, all of which can be explored programmatically, as we will see in future examples.

Introducing the World Computer

You've now created a wallet and sent and received ether. So far, we've treated Ethereum as a cryptocurrency. But Ethereum is much, much more. In fact, the cryptocurrency function is subservient to Ethereum's function as a decentralized world computer. Ether is meant to be used to pay for running smart contracts, which are computer programs that run on an emulated computer called the EVM.

The EVM is a global singleton, meaning that it operates as if it were a global single-instance computer, running everywhere. Each node on the Ethereum network runs a local copy of the EVM to validate contract execution, while the Ethereum blockchain records the changing state of this world computer as it processes transactions and smart contracts. We'll discuss this in much greater detail in Chapter 14.

Externally Owned Accounts and Contracts

The type of account you created in the MetaMask wallet is called an externally owned account (EOA). EOAs are those that have a private key; having the private key means control over access to funds or contracts.

You're probably guessing that there is another type of account. That other type of account is a contract account. A contract account has smart contract code, which a simple EOA can't have. Furthermore, a contract account does not have a private key. Instead, it is owned (and controlled) by the logic of its smart contract code: the software program recorded on the Ethereum blockchain at the contract account's creation and executed by the EVM.

Contracts have addresses, just like EOAs. Contracts can also send and receive ether, just like EOAs. However, when a transaction destination is a contract address, it causes that contract to run in the EVM, using the transaction—and the transaction's data—as its input. In addition to ether, transactions can contain data indicating which specific function in the contract to run and what parameters to pass to that function. In this way, transactions can call functions within contracts.

Note that because a contract account does not have a private key, it cannot initiate a transaction. Only EOAs can initiate transactions, but contracts can react to transactions by calling other contracts, building complex execution paths.

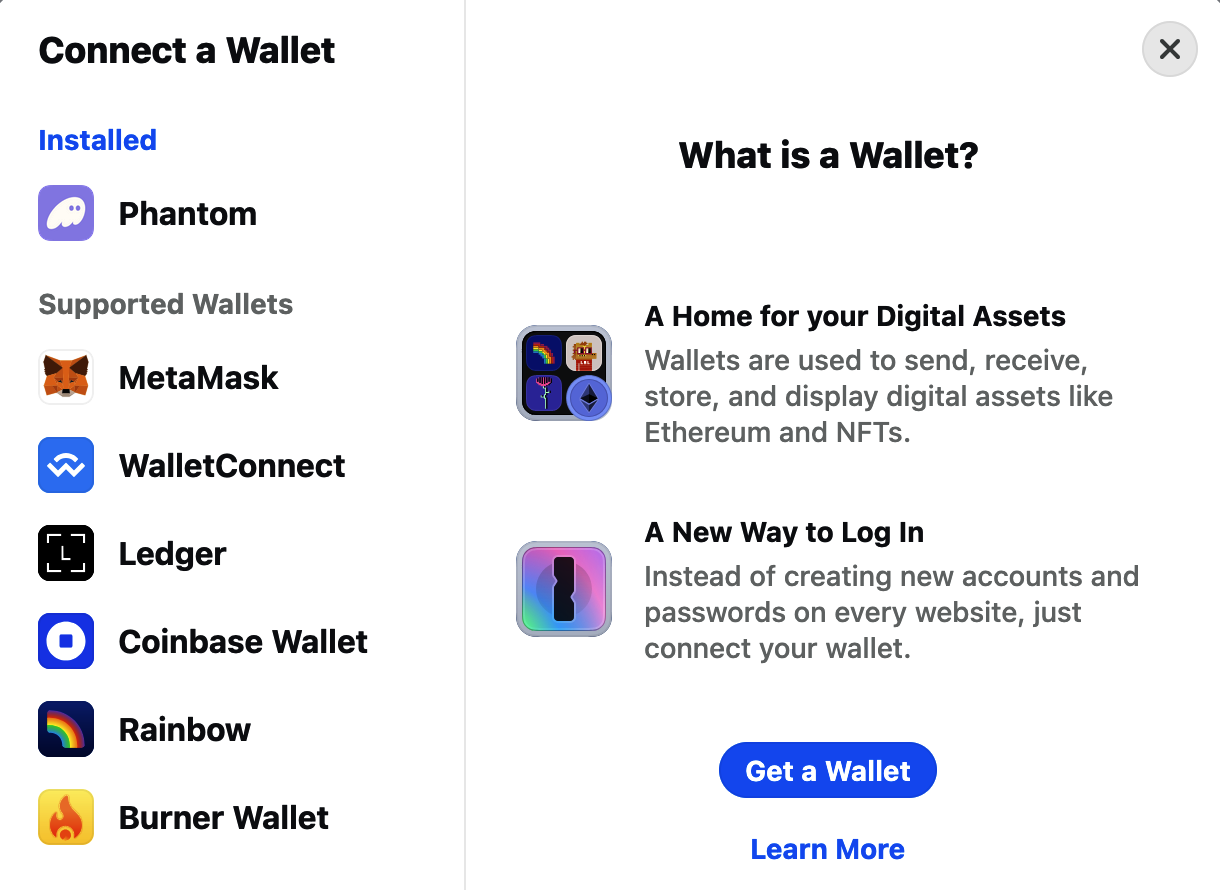

In the next few sections, we will write our first contract. You will then learn how to create, fund, and use that contract with your MetaMask wallet and test ether on the Sepolia test network.

A Simple Contract: A Test Ether Faucet

Ethereum has a few different high-level languages, all of which can be used to write a contract and produce EVM bytecode. You can read about the most prominent and interesting ones in Chapter 7. One high-level language is by far the dominant choice for smart contract programming: Solidity. Solidity was created by Gavin Wood and has become the most widely used language in Ethereum (and beyond). We'll use Solidity to write our first contract.

For our first example (Example 2-1), we will write a contract that controls a faucet. You've already used a faucet to get test ether on the Sepolia test network. A faucet is a relatively simple thing: it gives out ether to any address that asks and can be refilled.

Example 2-1. Faucet.sol: a Solidity contract implementing a faucet

pragma solidity 0.8.26;

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

// Our first contract is a faucet!

contract Faucet {

// Give out ether to anyone who asks

function withdraw(uint256 _withdrawAmount, address payable _to) public {

// Limit withdrawal amount

require(_withdrawAmount <= 1000000000000);

// Send the amount to the address that requested it

_to.transfer(_withdrawAmount);

}

// Function to receive Ether. msg.data must be empty

receive() external payable {}

// Fallback function is called when msg.data is not empty

fallback() external payable {}

}

This is a very simple contract, about as simple as we can make it. It is also a flawed contract, demonstrating a number of bad practices and security vulnerabilities. We will learn by examining many of its flaws in later sections. But for now, let's look at what this contract does and how it works, line by line. You will quickly notice that many elements of Solidity are similar to existing programming languages, such as JavaScript, Java, or C++.

The first line is the pragma statement:

pragma solidity 0.8.26;

By including this line at the top of a Solidity source file, you ensure that the code is compiled with version 0.8.26 of the Solidity compiler, ensuring compatibility and avoiding potential issues that might arise from using a different compiler version.

Next is a comment indicating that the smart contract is licensed under the GPL-3.0 license:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: GPL-3.0

This is important for legal and compliance reasons because it informs users and developers about their rights and obligations concerning the use and distribution of the code.

Comments are for humans to read and are not included in the executable EVM bytecode. We usually put them on the line before the code we are trying to explain, or sometimes on the same line. Comments start with two forward slashes: //. Everything from the first slash until the end of that line is treated the same as a blank line and ignored.

This is also a comment:

// Our first contract is a faucet!

The next line is where our actual contract starts:

contract Faucet {

This line declares a contract object, similar to a class declaration in other object-oriented languages. The contract definition includes all the lines between the curly braces ({}), which define a scope, much like how curly braces are used in many other programming languages.

Next, we declare the first function of the Faucet contract:

function withdraw(uint256 _withdrawAmount, address payable _to) public {

The function is named withdraw, and it takes one unsigned integer (uint256) named _withdrawAmount and an address payable named _to. It is declared as a public function, meaning it can be called by other contracts. The function definition follows, between curly braces. The first part of the withdraw function sets a limit on withdrawals:

require(_withdrawAmount <= 1000000000000);

It uses the built-in Solidity function require to test a precondition: that the _withdrawAmount is less than or equal to 1,000,000,000,000 wei, which is the base unit of ether (see Table 2-1) and equivalent to 0.000001 ether. If the withdraw function is called with a withdraw_amount greater than that amount, the require function here will cause contract execution to stop and fail with an exception. Note that statements need to be terminated with a semicolon in Solidity.

This part of the contract is the main logic of our faucet. It controls the flow of funds out of the contract by placing a limit on withdrawals. It's a very simple control but can give you a glimpse of the power of a programmable blockchain: decentralized software controlling money.

Here we have the first design flaw of the contract. It is not a security flaw, but it would be better to always add an error message to the require statement. This way, when a user's transaction fails due to a require statement, the reason is clear.

The corrected require statement is:

require(_withdrawAmount <= 1000000000000, "The requested amount is too much, try a smaller amount!");

Next comes the actual withdrawal:

_to.transfer(_withdrawAmount);

A couple of interesting things are happening here. The function transfer is a built-in function that transfers ether from the current contract to another specified address—in this case, the _to address. The transfer function takes an amount as its only argument. We pass the _withdrawAmount value that was the parameter to the withdraw function declared a few lines earlier.

This is possible because the _to address was defined as payable. The built-in functions transfer and send can be called only on payable addresses. Here is the second flaw in the code: while transfer is perfectly fine if an EOA calls the withdraw function, it becomes problematic if another contract triggers this function. In that case, the transaction might fail because the transfer function can utilize only up to 2,300 gas, and multiple contract calls will likely exceed this limit. To fix this issue, you can use the built-in call function instead of transfer and send. However, this built-in function needs to be handled properly to avoid security flaws. For now, we will leave the built-in transfer function as is.

The very next line is the closing curly brace, indicating the end of the definition of our withdraw function.

Next, we declare two more functions:

receive() external payable {}

fallback() external payable {}

These functions are the fallback and receive functions, which are called if the transaction that triggered the contract didn't name any of the declared functions in the contract, or any function at all, or didn't contain data. Contracts can have these functions and are usually the ones that receive ether. When msg.data is empty, the receive function will be triggered; when msg.data is not empty, the fallback function will be triggered.

Right below our fallback function is the final closing curly brace, which closes the definition of the contract Faucet. That's it!

Compiling the Faucet Contract

Now that we have our first example contract, we need to use a Solidity compiler to convert the Solidity code into EVM bytecode so that it can be executed by the EVM on the blockchain itself.

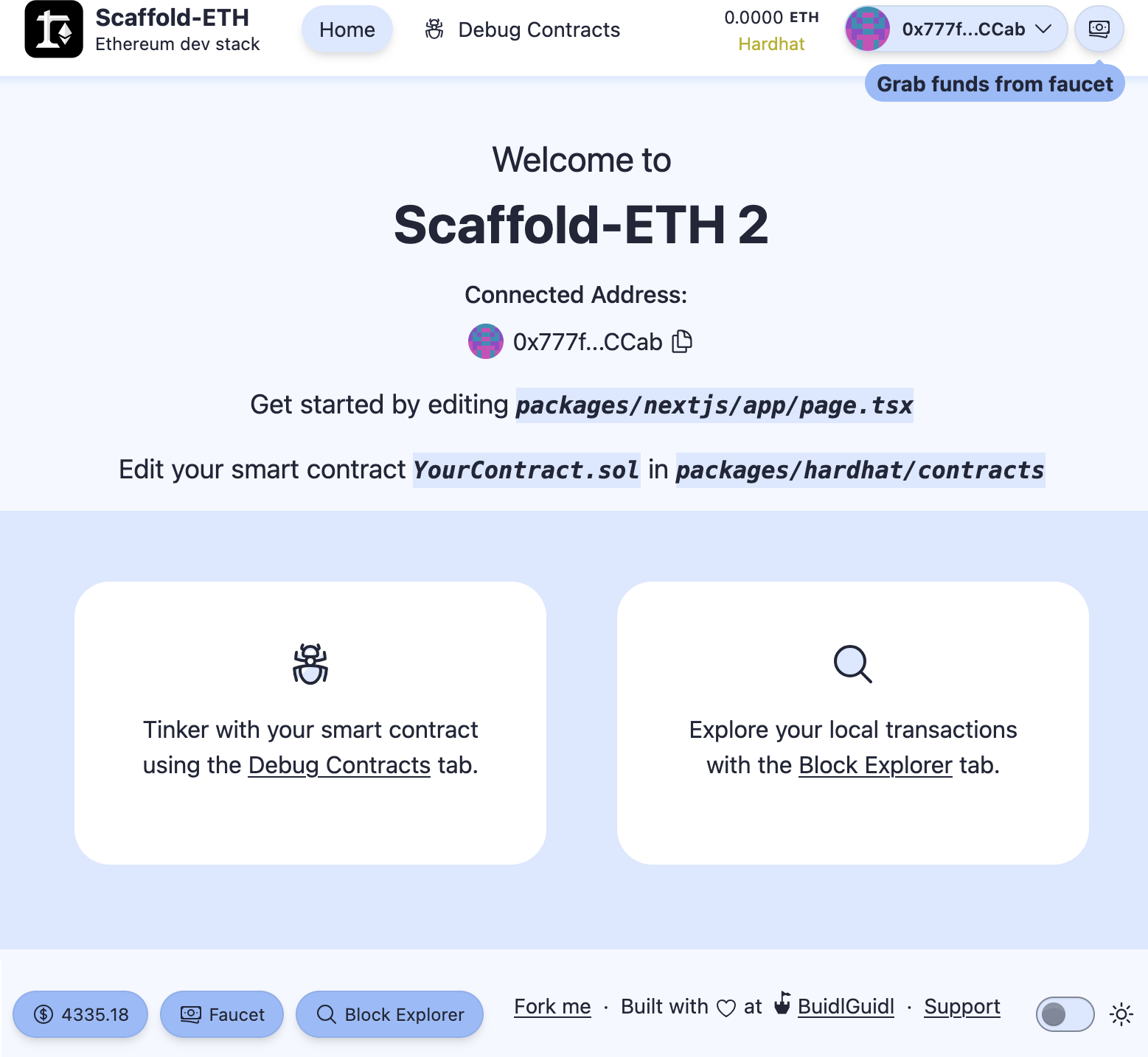

The Solidity compiler comes as a standalone executable, as part of various frameworks, and bundled in IDEs. To keep things simple, we will use one of the more popular IDEs: Remix.

Use your Chrome browser (with the MetaMask wallet you installed earlier) to navigate to the Remix IDE.

When you first load Remix, it will start with a sample contract called Storage.sol. We don't need that, so close it by clicking the x on the corner of the tab, as seen in Figure 2-12.

Figure 2-12. Closing the default example tab

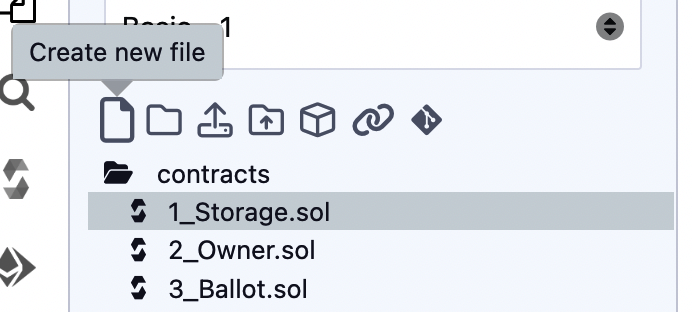

Now, create a new file, as shown in Figure 2-13. Name the new file Faucet.sol.

Figure 2-13. Creating a new contract

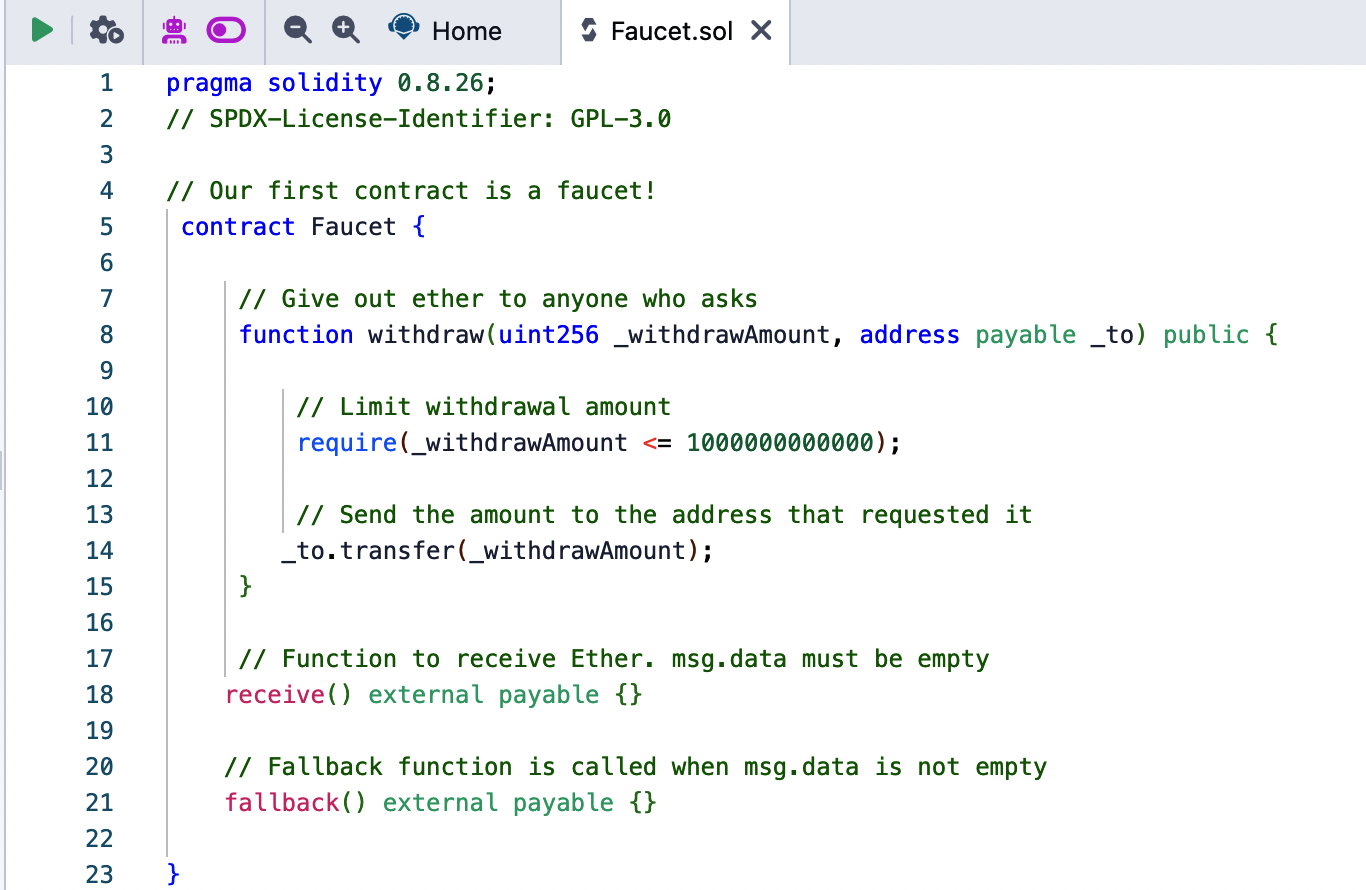

Once you have the new tab open, copy and paste the code from our example Faucet.sol, as shown in Figure 2-14.

Figure 2-14. Copying the Faucet example code into the new contract

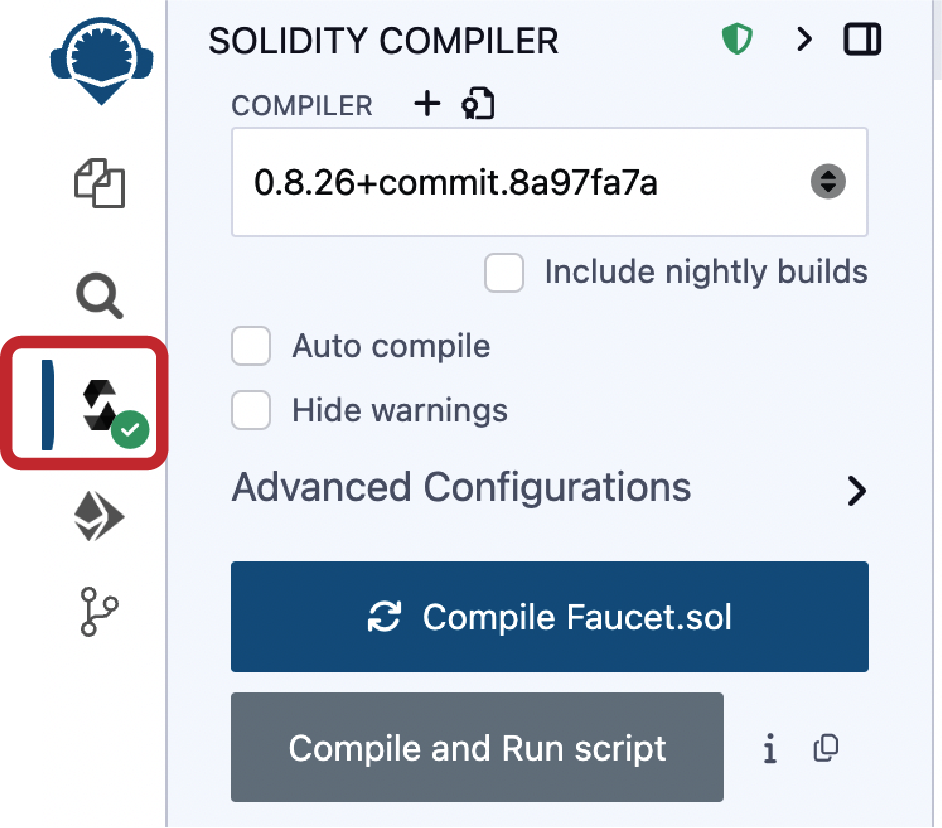

Once you have loaded the Faucet.sol contract into the Remix IDE, navigate to the compile section of Remix and click Compile Faucet.sol. If all goes well, you will see a green box (see Figure 2-15).

Figure 2-15. Remix successfully compiles the Faucet.sol contract

If something goes wrong, the most likely problem is that the Remix IDE is using a version of the Solidity compiler that is different from 0.8.26. In that case, our pragma directive will prevent Faucet.sol from compiling. To change the compiler version, go to the Compiler tab, set the version to 0.8.26, and try again.

The Solidity compiler has now compiled our Faucet.sol into EVM bytecode. If you are curious, the bytecode looks like this:

6080604052348015600e575f80fd5b506101af8061001c5f395ff3fe608060405260043610610020575f3560

e01c8062f714ce1461002957610027565b3661002757005b005b348015610034575f80fd5b5061004f600480

360381019061004a919061013b565b610051565b005b64e8d4a51000821115610062575f80fd5b8073ffffff

ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff166108fc8390811502906040515f60405180830381858888f19350

5050501580156100a5573d5f803e3d5ffd5b505050565b5f80fd5b5f819050919050565b6100c0816100ae56

5b81146100ca575f80fd5b50565b5f813590506100db816100b7565b92915050565b5f73ffffffffffffffff

ffffffffffffffffffffffff82169050919050565b5f61010a826100e1565b9050919050565b61011a816101

00565b8114610124575f80fd5b50565b5f8135905061013581610111565b92915050565b5f80604083850312

15610151576101506100aa565b5b5f61015e858286016100cd565b925050602061016f85828601610127565b

915050925092905056fea26469706673582212207de2f4d88c747c9332dceef5dcd739f3380ec8a8c2167a29

2ba64ee24fa32a8a64736f6c634300081a0033

Aren't you glad you are using a high-level language like Solidity instead of programming directly in EVM bytecode? Us too!

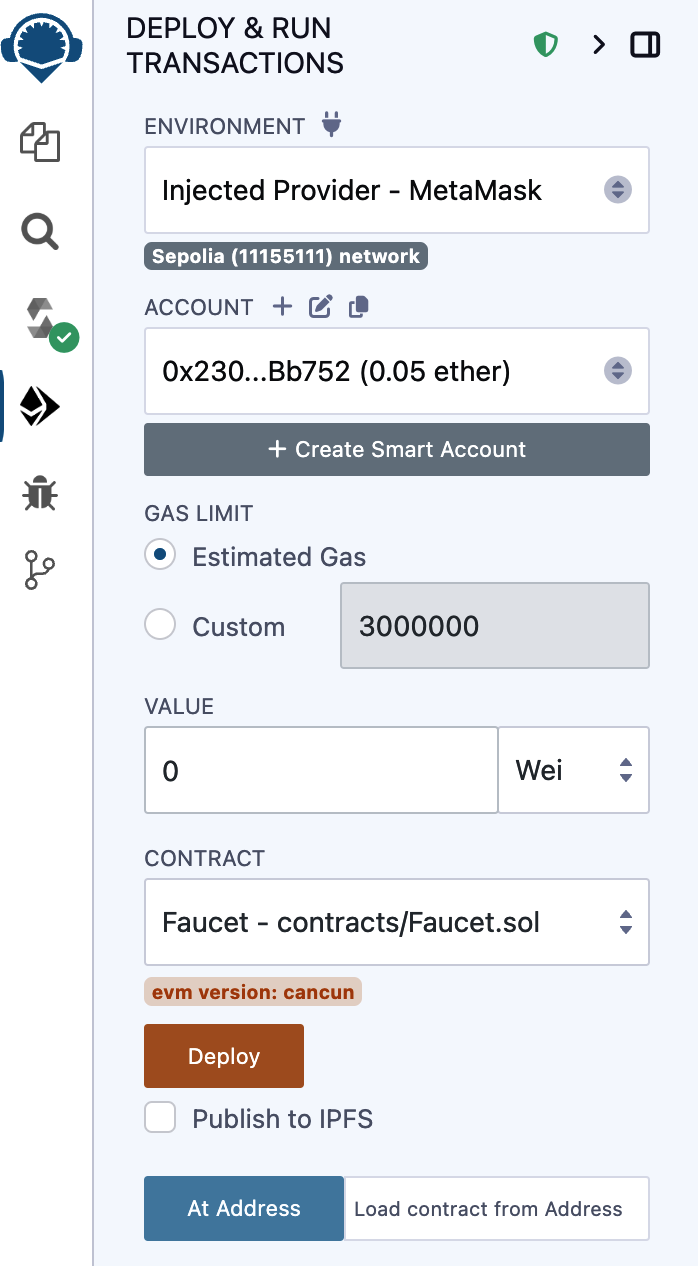

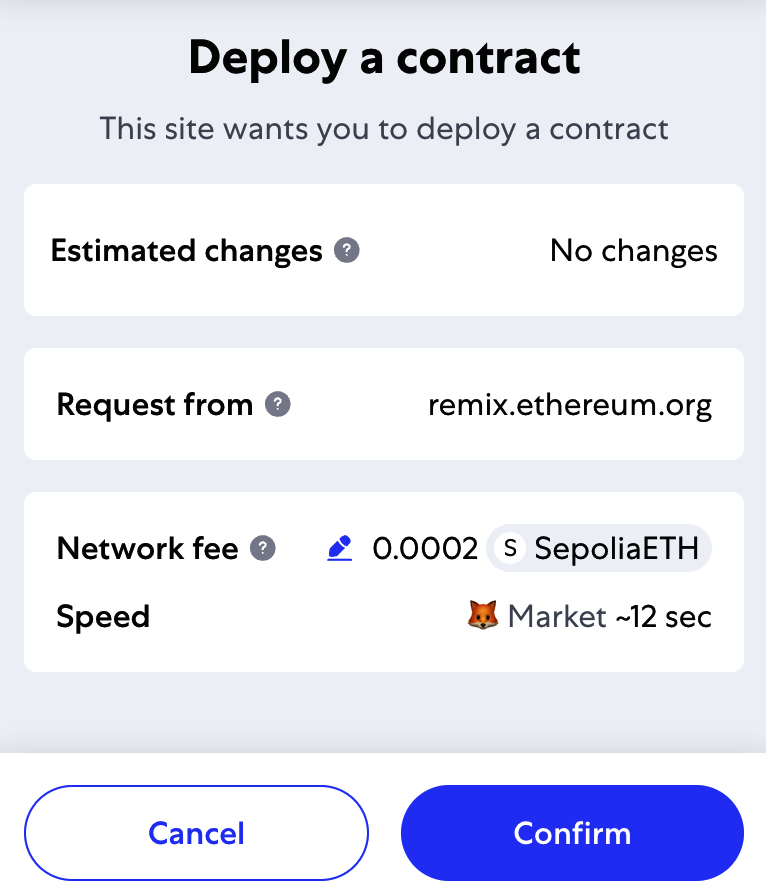

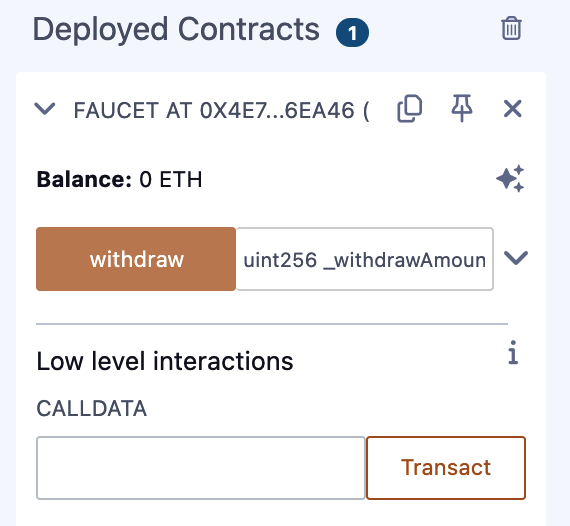

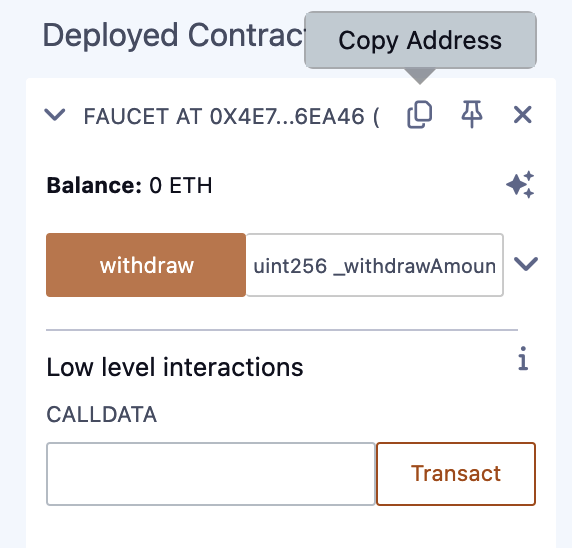

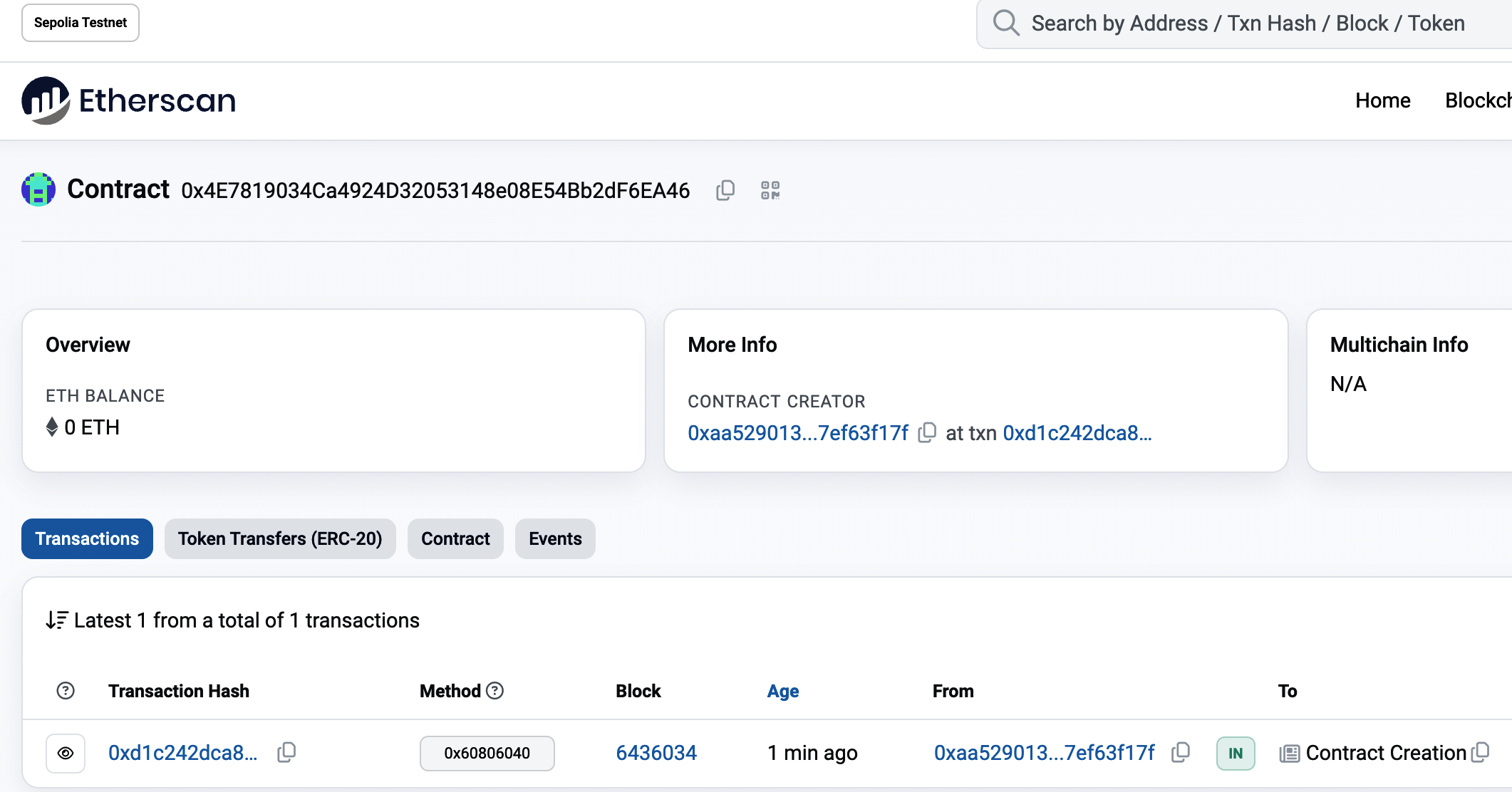

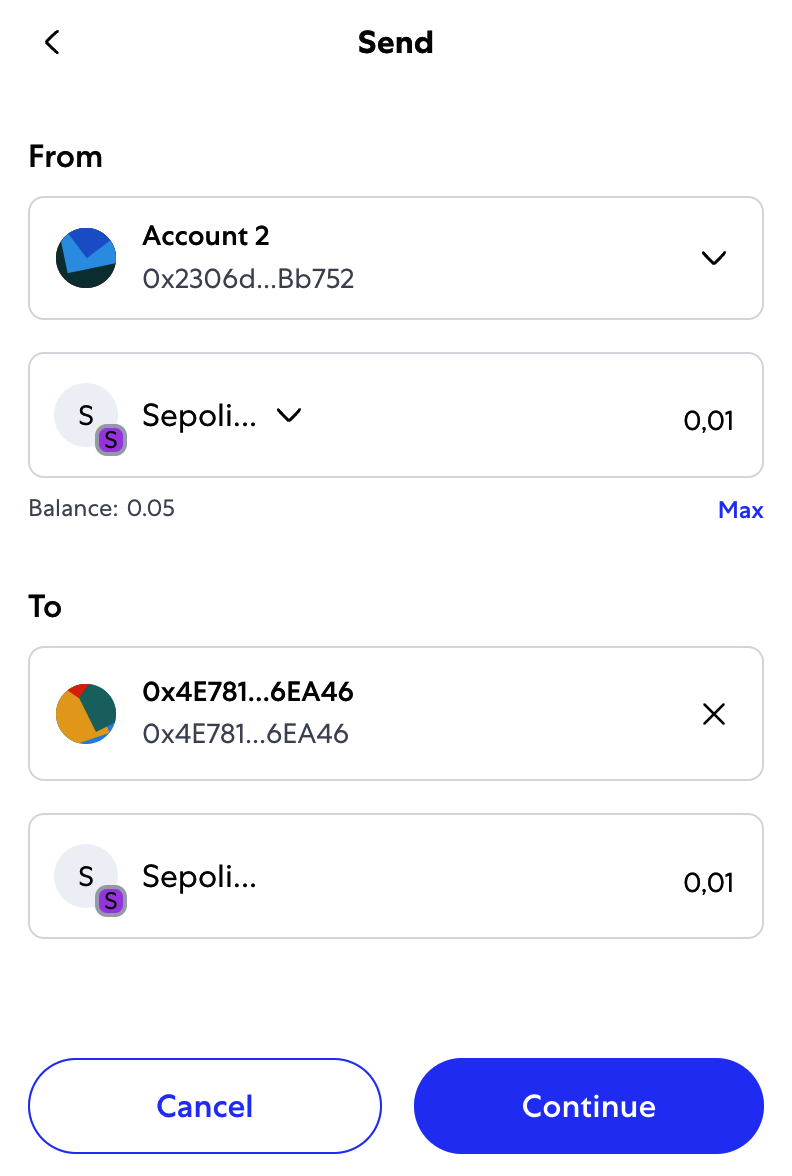

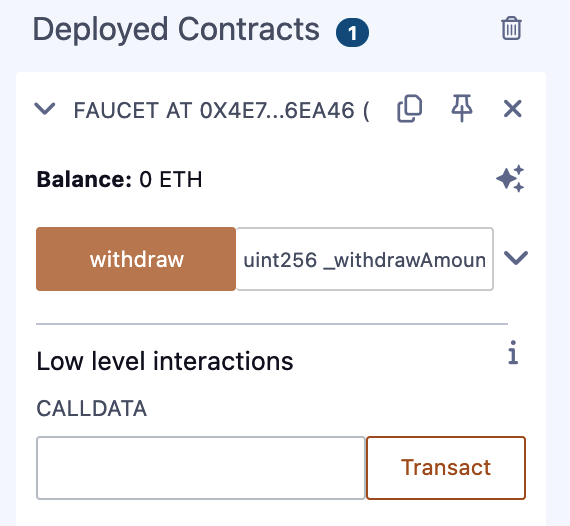

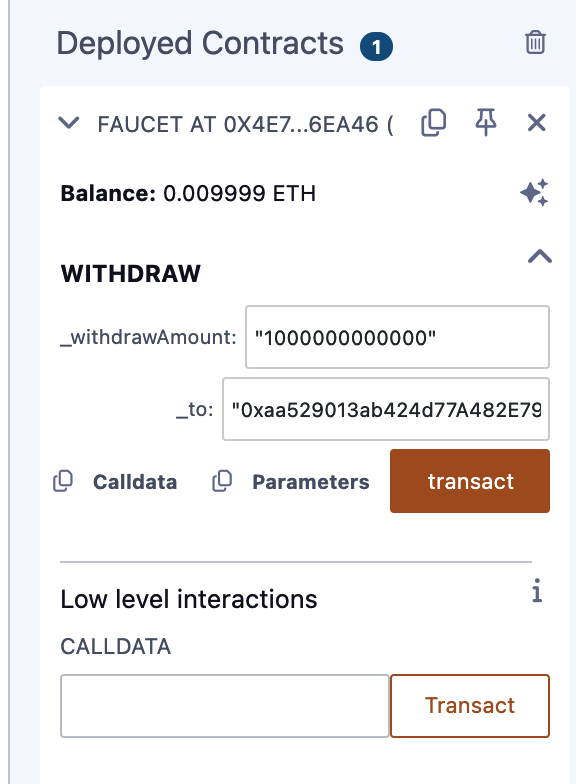

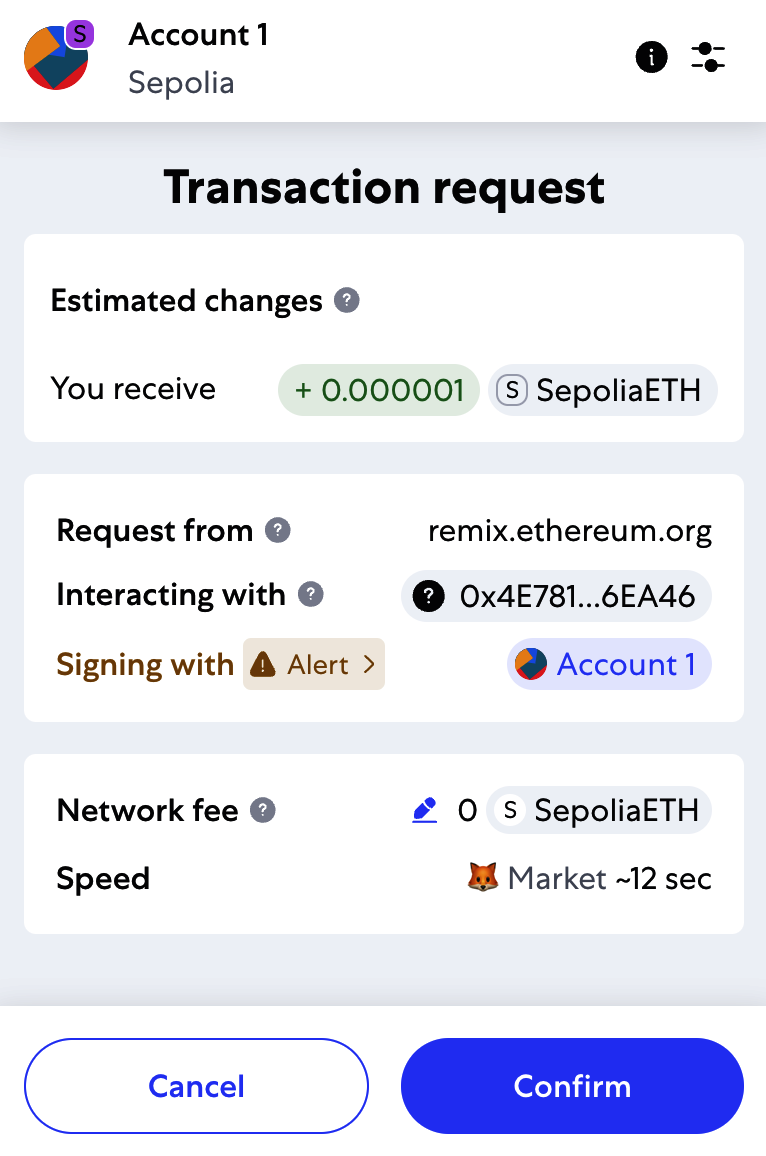

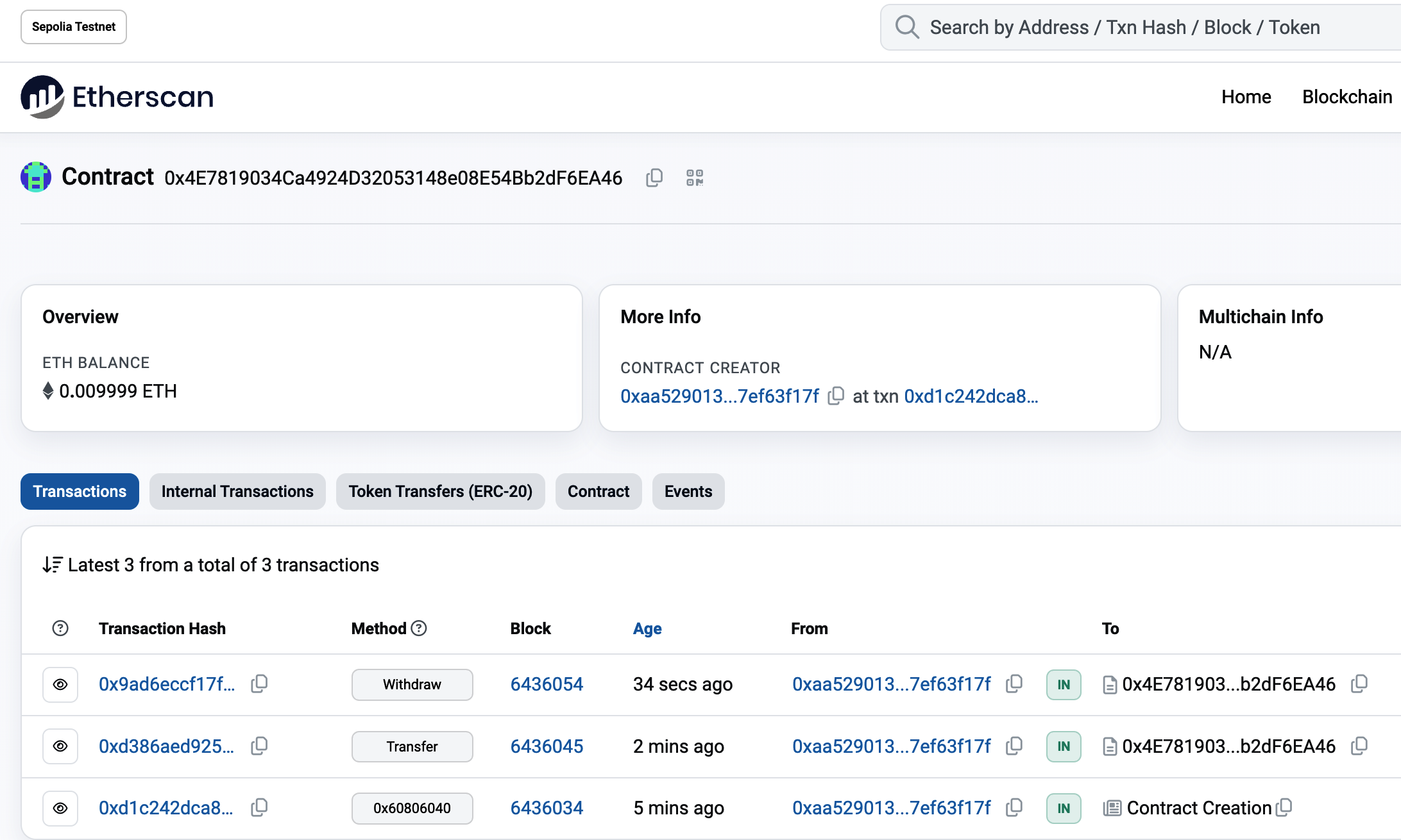

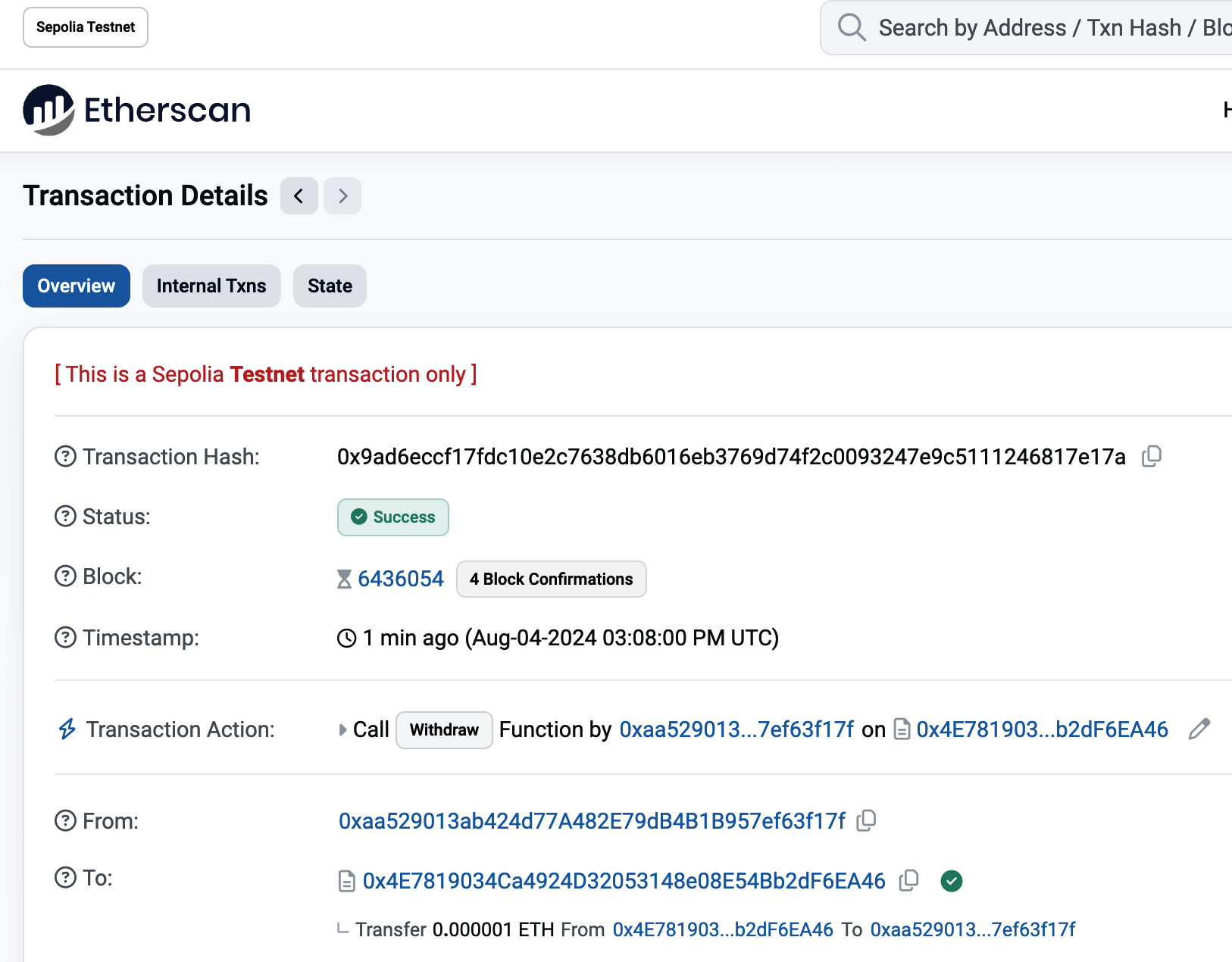

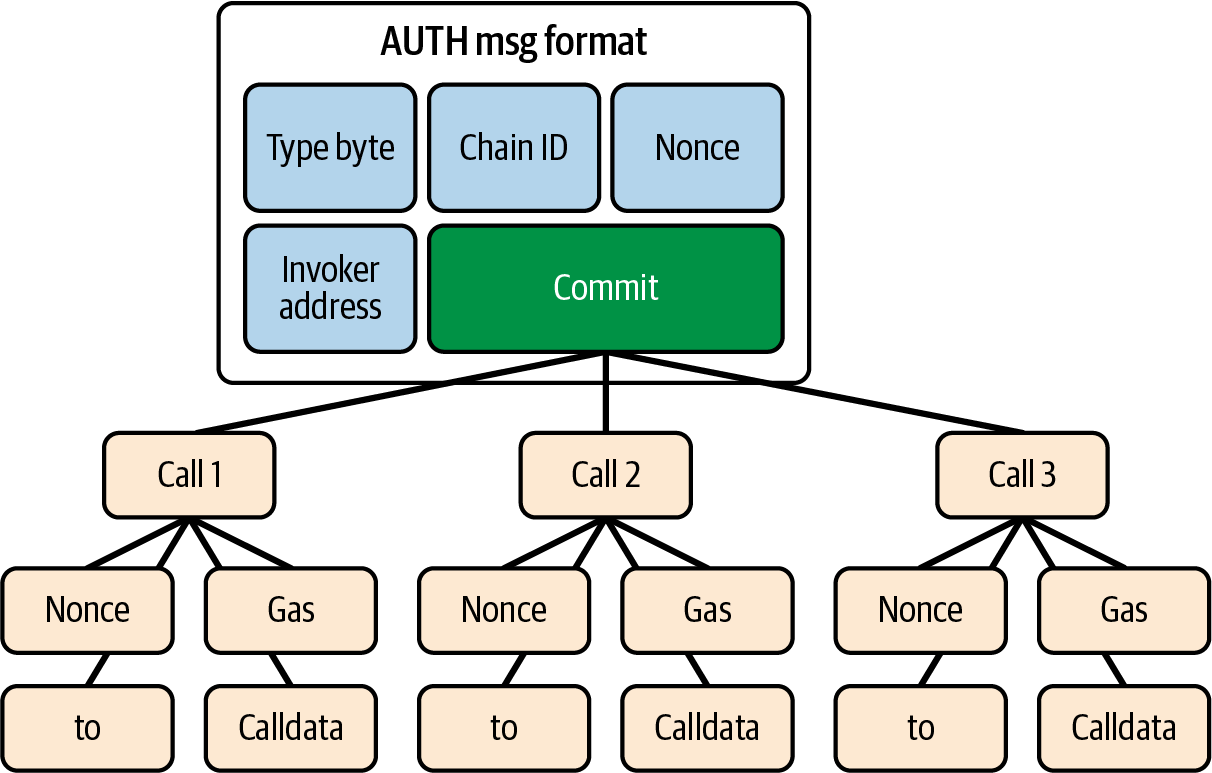

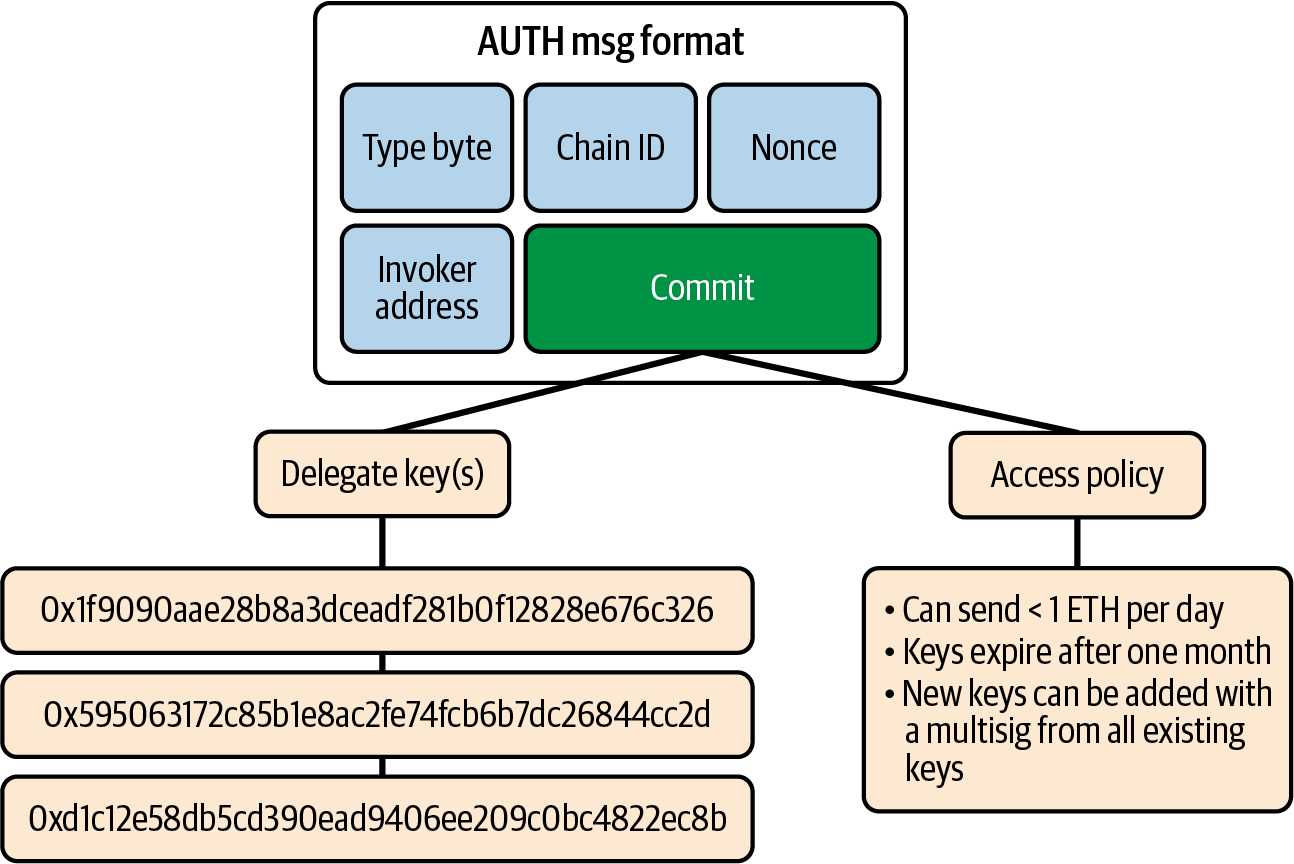

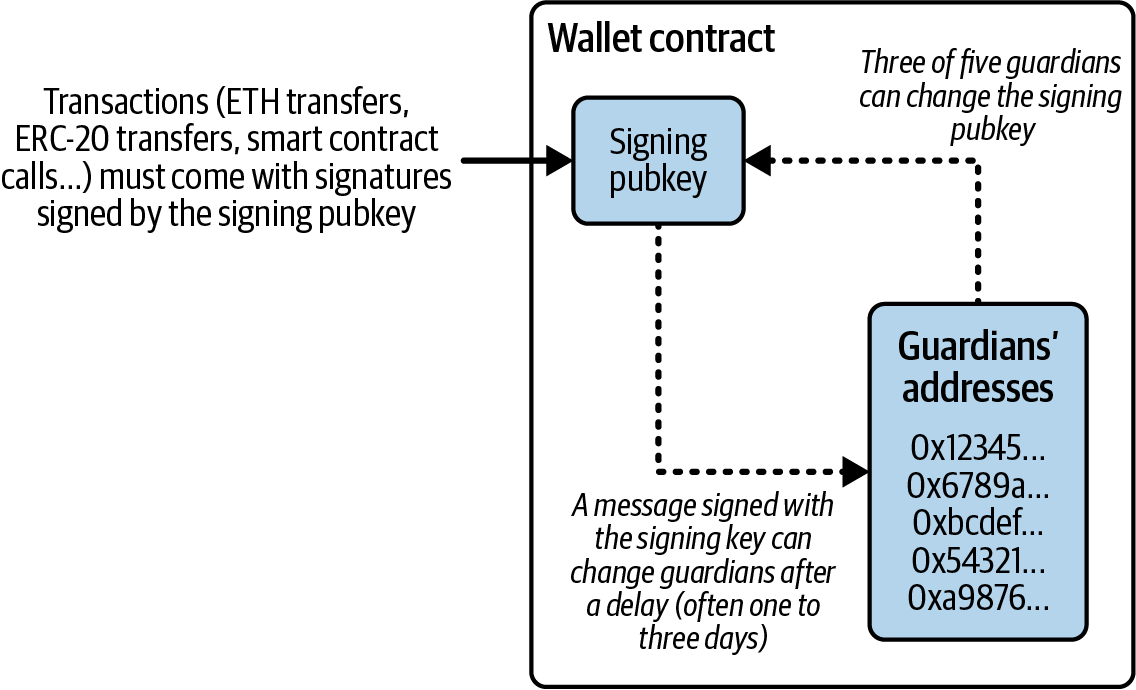

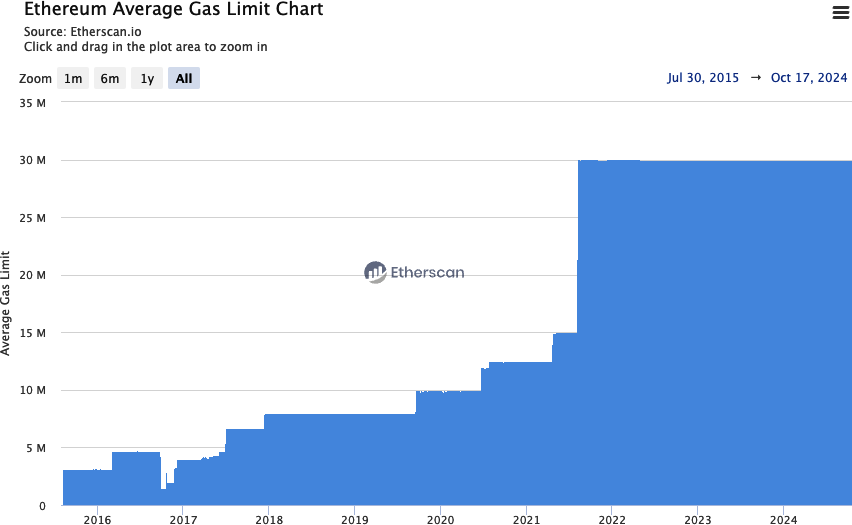

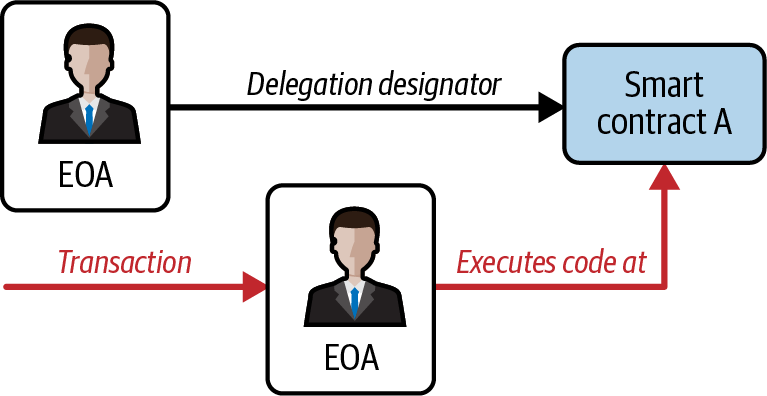

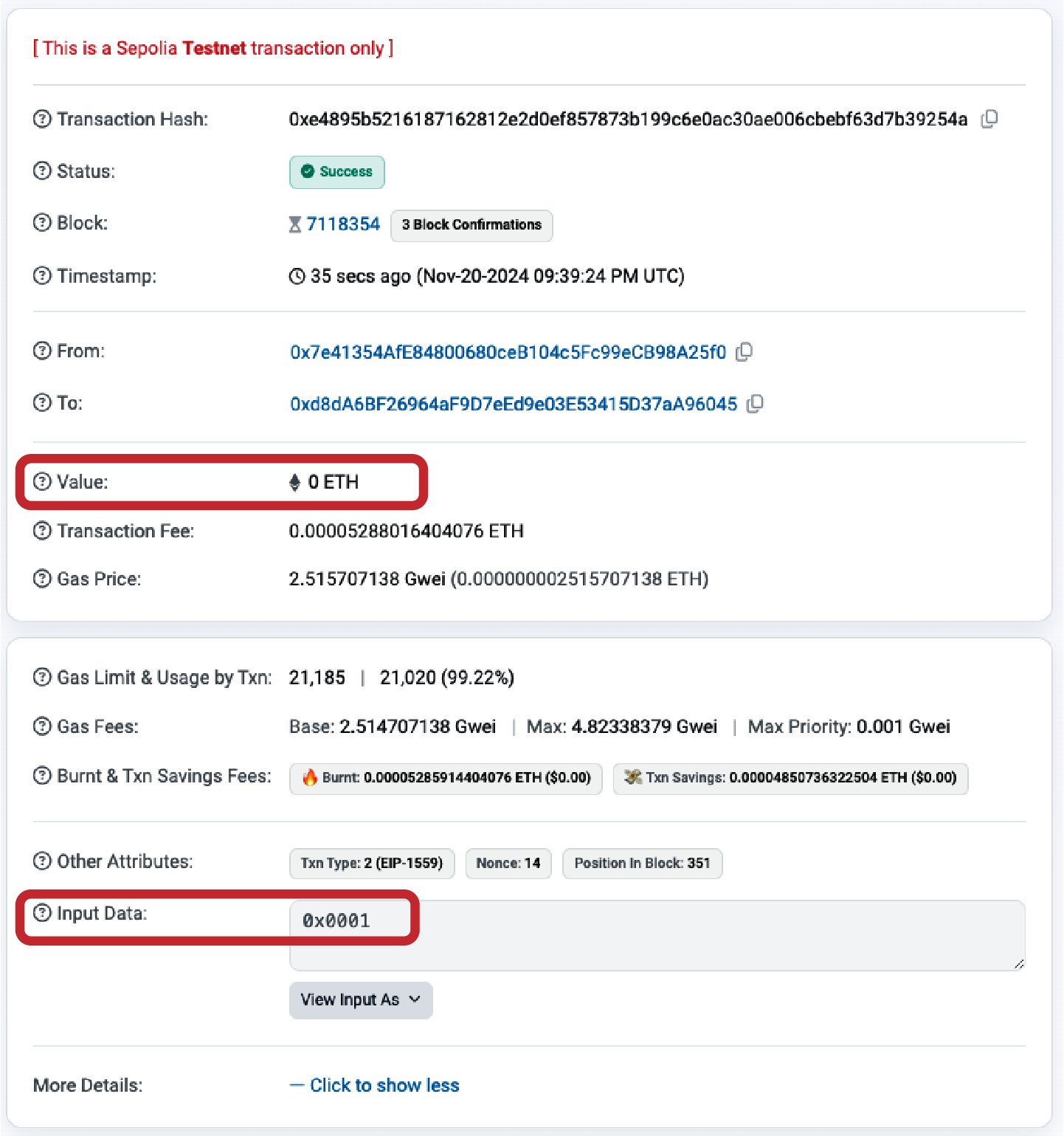

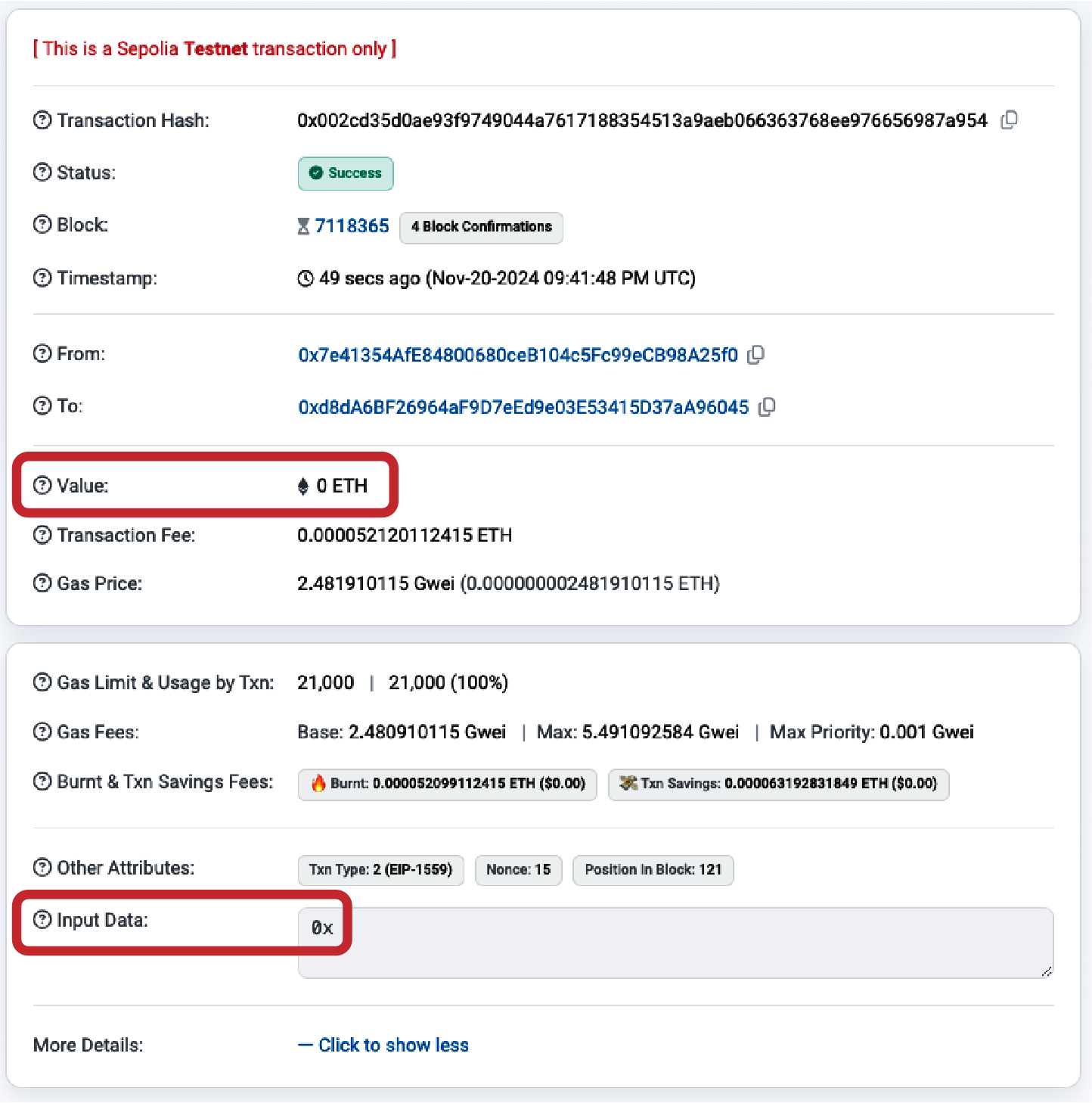

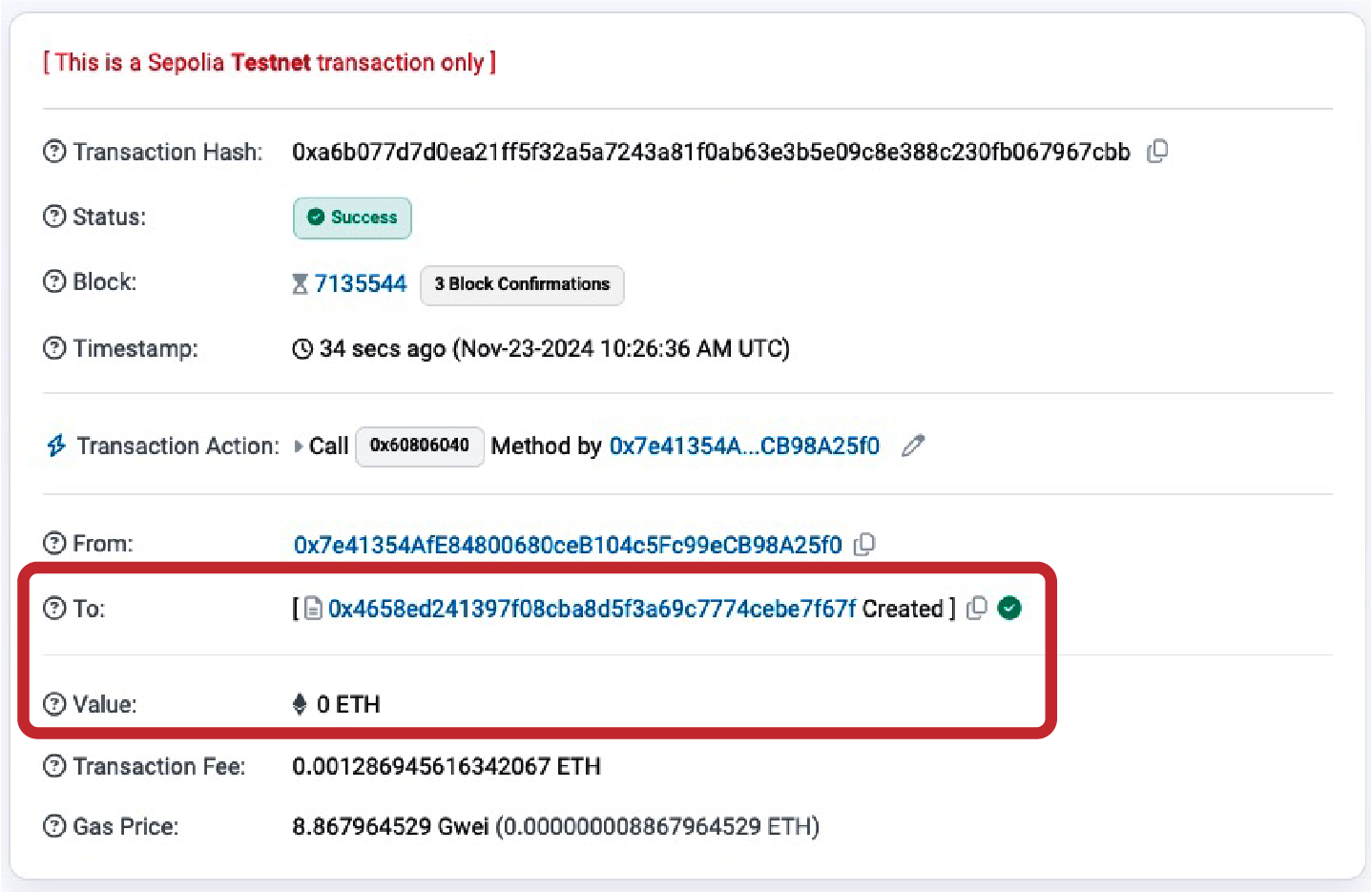

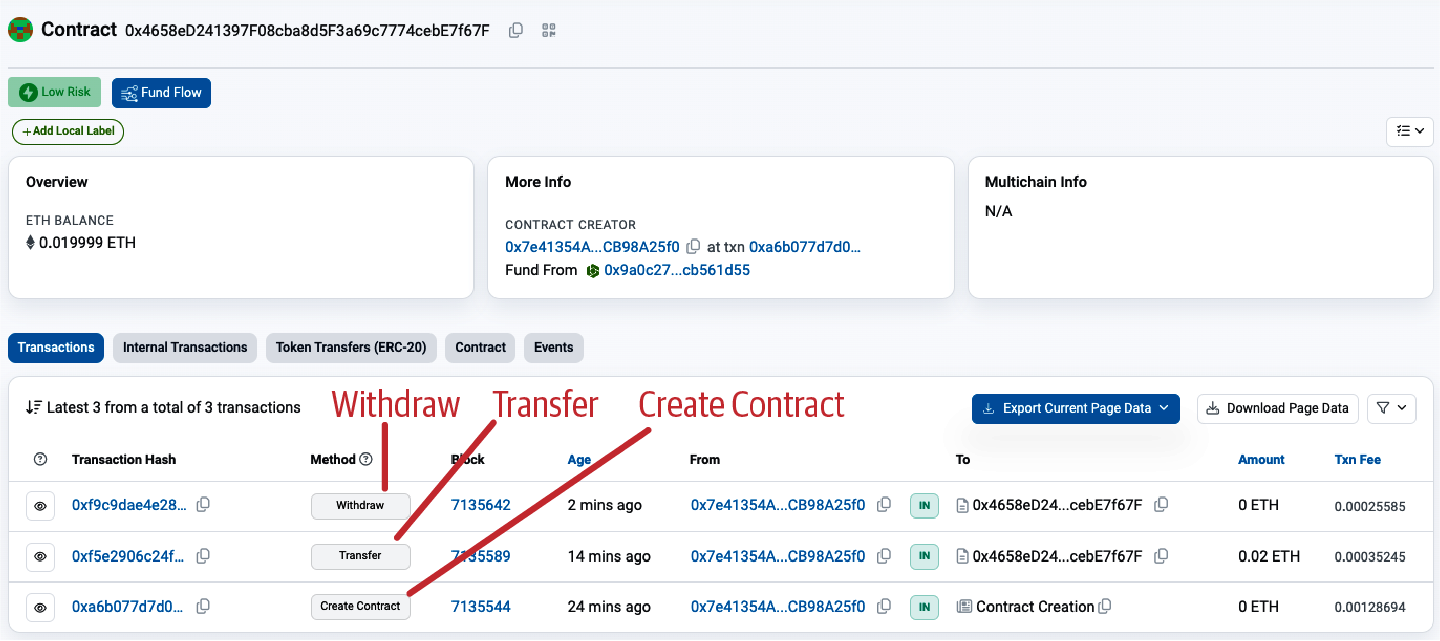

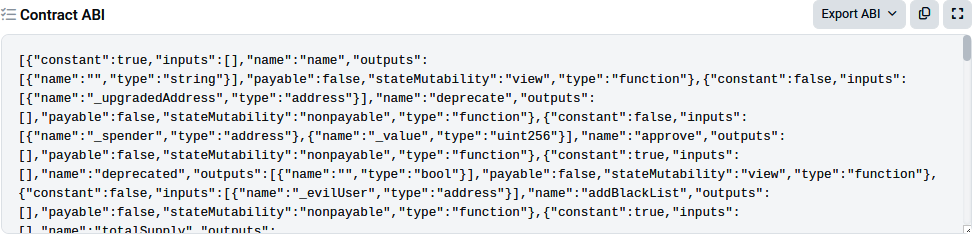

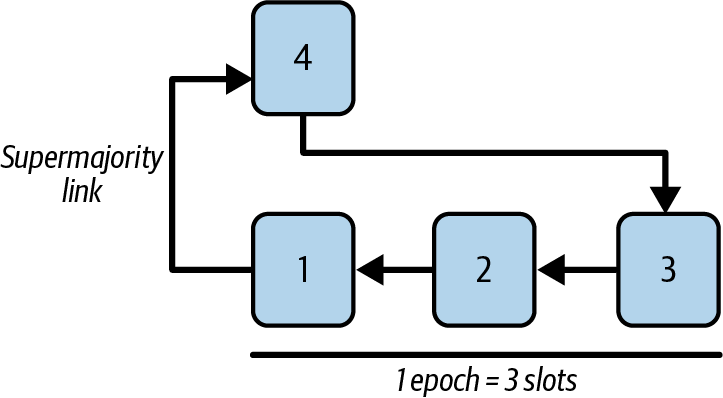

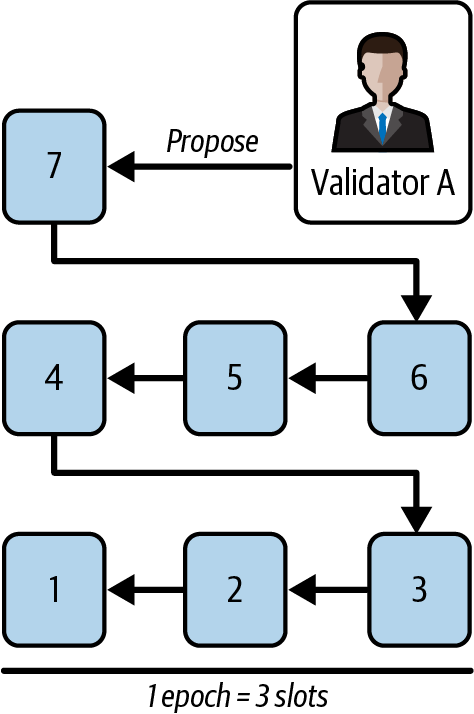

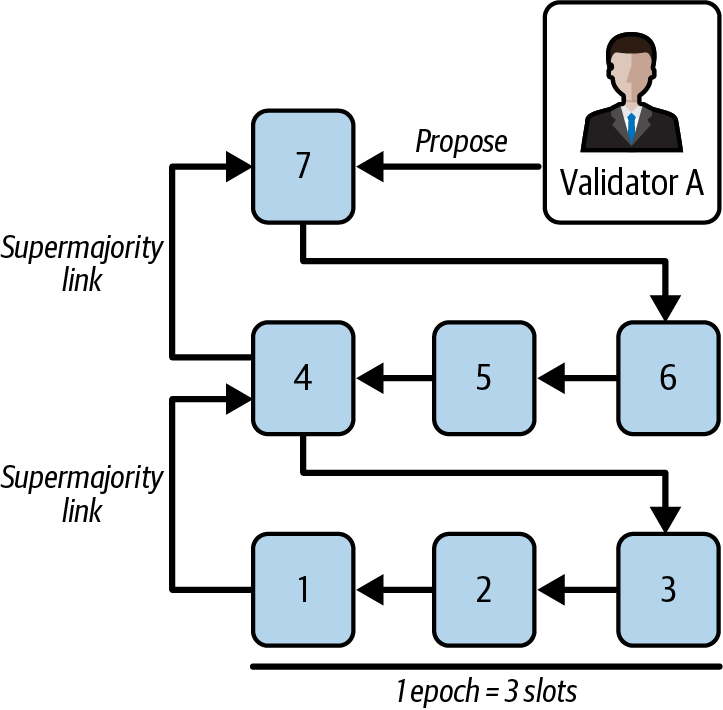

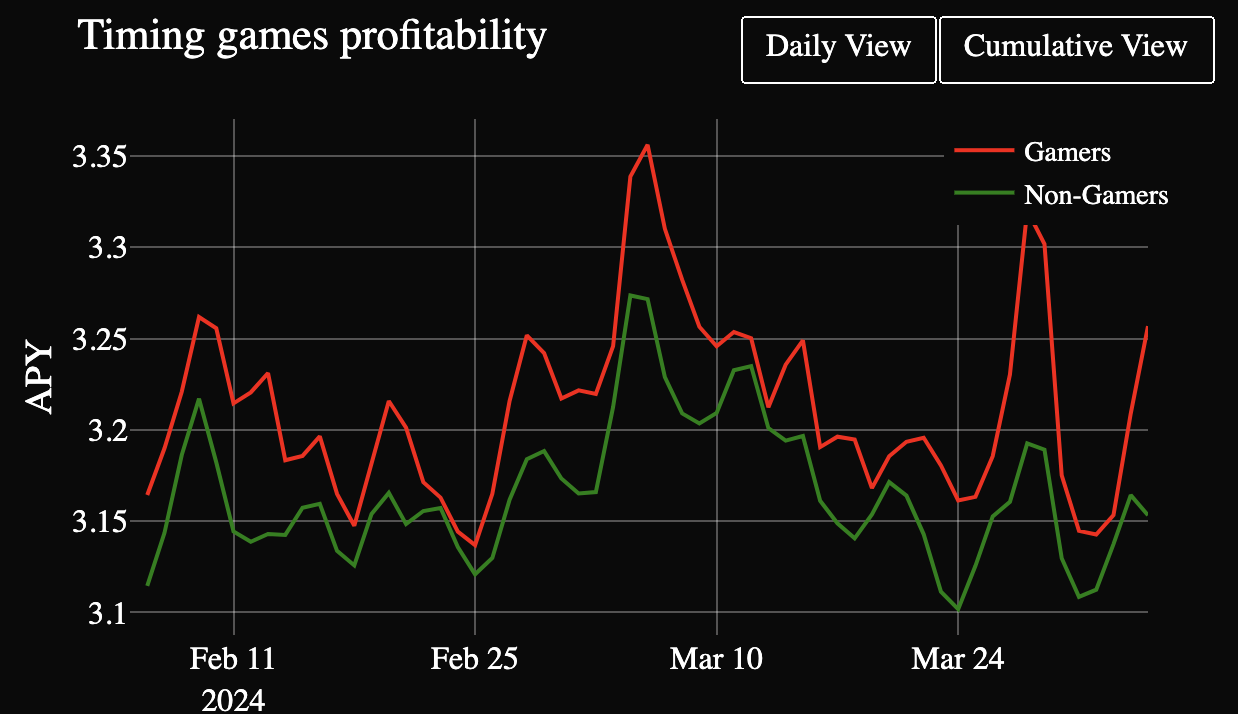

Creating the Contract on the Blockchain